Here are some facts: climate change is real, catastrophic and anthropogenic. Global warming is not a hoax, is happening at an unprecedented rate and is not part of natural fluctuations in global temperatures over geological time.

You’d be hard pressed to find a climate scientist who would disagree significantly with anything in the previous two sentences – though they do like to fuss over the details. Somehow though, these facts are all contested outside the walls of the academy. We – and by we, I mean scientists in general – have failed to convey our confidence in these facts to the broadest possible range of people, and action on the climate emergency is weak and laden with inertia. A mega-funded, profit-driven disinformation industrial complex has done its very best to lobby and cheat and lie in contesting the facts. Political polarisation doesn’t help, with climate action perceived and characterised as a left-liberal position, the preserve of self-regarding Hollywood types and naive youths who glue themselves to roads and chuck soup at art.

And now here I am, a left-leaning centrist reviewing a French graphic novel about the climate crisis in the Guardian. All that’s missing is a spot of cold-water swimming and a nod to polyamory.

But World Without End is already a global smash, an international bestseller, after first being published in France. It is big and bold in the style of the other graphic novels that broke out of their niches: Maus – Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer-winning 1991 murine tale of the Holocaust, with Jews as mice and Nazis cats; Persepolis, Marjane Satrapi’s 2003 memoir of growing up in Iran, and Palestine by journalist Joe Sacco, his record of life on the ground in Gaza in the 1990s. (Fascism; conflict in the Middle East – each of these books is more than 20 years old. Plus ça change.)

World Without End is written as a sort of Socratic dialogue between a climate expert (Jean-Marc Jancovici) and an ignorant illustrator (Christophe Blain), who turns the facts into pictures. Like that other icon of mainstream climate campaigning, Al Gore’s 2006 film An Inconvenient Truth, there is plenty of lecturing and plenty of graphs (I like the occasional graph, but do wonder whether everyone feels the same). It’s witty, charmingly crude at times, but has a tendency to break the fourth wall, as it were, nodding to the reader and inviting us to be willingly lectured. I don’t love this, and I am literally a lecturer. I constantly worry about proselytising or hectoring audiences – look how much I know. This is a form of what we refer to in the business as the “deficit model”, which suggests that the public’s ignorance is the cause of their scepticism. It’s a theory of science communication that has been largely debunked as ineffective, but it abounds, perhaps because science is hard and technical, and most people stop studying it when they are 16.

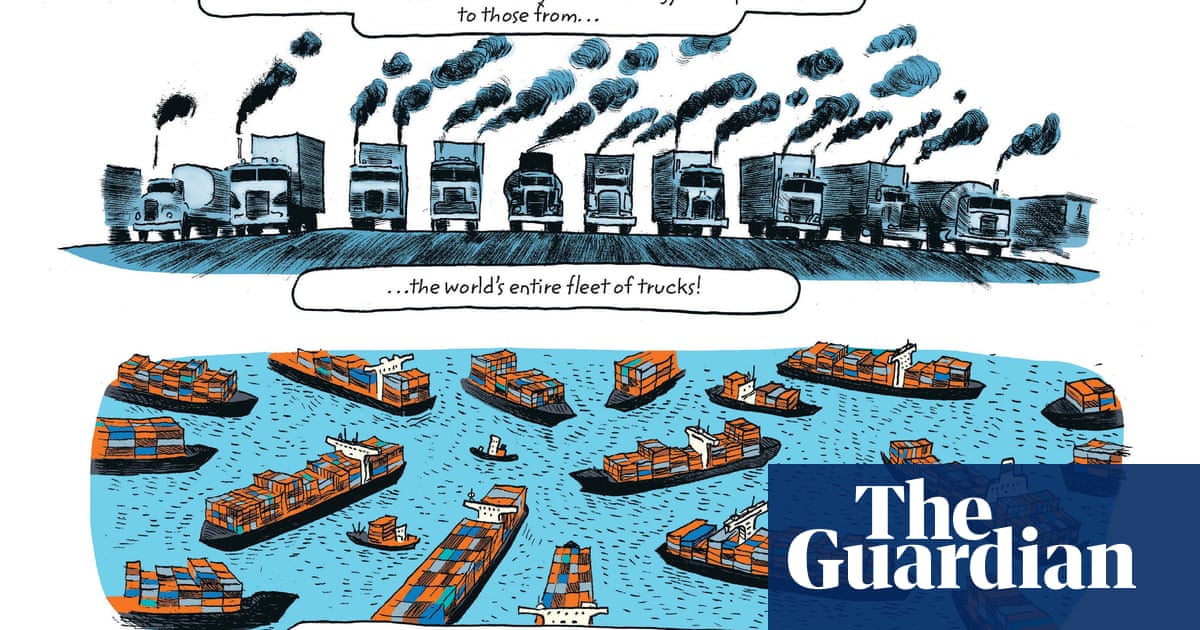

The information density in World Without End is indeed incredible, overwhelming at times, and most of the facts concern the prime cause of anthropogenic climate change, which is our vampiric addiction to energy. Some of these nuggets are powerful (15,000km in a car is equivalent to 70,000 days of slavery), others are confusing (a ride in an elevator is the same as 50 cyclists, but doing what, and for how long?). It makes a strong case for the interconnectedness of life on Planet Earth, from brushing your teeth to shopping for food, and shows how climate change is already having a political impact – from mass migration to social unrest and much more. How we live, what we eat, how we grow it, how we travel, how we communicate: every aspect of life in the last couple of hundred years has been dependent on the high concentration of energy stored in the chemical bonds of hydrocarbons. The book’s granular descriptions of the way the world actually works, from molecules to people to the economy is persuasive.

Not that I need to be persuaded, at least about the crisis we face. There are, however, sections that are sloppy, as well as preachy. Towards the end, the authors start rattling on about various neurological functions and evolutionary precepts that apparently explain our self-defeating, planet-eating habits. But you can’t just blame human behaviour on the striatum, a part of the brain involved in reward biochemistry. The authors try to instil a message of hope, which is good, but land on the public intellectual platform otherwise occupied by vapid soothsayers such as Jordan Peterson or Yuval Noah Harari, which is bad, with half-understood or ultra-simplified explanations of wickedly complex scientific ideas all asserted as powerful fact.

Perhaps this does not matter. The fight is on, and it is existential for humankind. Stories are often more compelling than hard data. This is vexing to those who spend their lives fussing over the details. That may be why, despite the fact I am the choir for a graphic novel about climate change, I found it mildly unsatisfactory. Yes, tell stories, and maybe then we can all sing louder from the same hymn sheet. But don’t hammer us with glibness.

after newsletter promotion