Sabine had traumatised only a few people in her life and one of them was her husband. She stood in their back garden and waited for Constantine to remove the camera from the tripod. It was Monday night. It was about to storm. The sun had set hours ago, and dinnertime had come and gone without mention.

“A reminder that we’re aiming for stark and otherworldly,” said Sabine. Despite her tone, she was not too dictatorial.

“The sky is actually purple,” said Constantine. He held his hand out, palm up, and looked at the cloud overhead.

Sabine unbuttoned her vinyl coat, smoothed her hair back behind her ears, and crouched at the base of their fruiting lemon tree, ready to be immortalised. These photos would be used to publicise her upcoming solo art exhibition. She loved seeing herself named as the photographer for any promotional material. Differentiating herself, no matter how subtly, from the other artists represented by the Goethe Gallery soothed her to no end.

Sabine had briefed Constantine on the importance of capturing the glossiness of her hair and her lively sanpaku eyes. Two aesthetics she was unwilling to compromise on. She’d demonstrated how she would dip her head at a severe angle so that a distinct white gap showed between her iris and the lower lid of her eye. Their garden needed to look untamed and junglelike in the background. The sky must be a deep navy. No stars! And.

“Get some of the lemons in,” said Sabine. It was imperative that the waxy lemons were lurid against all that green.

“Please,” said Constantine.

“Please,” said Sabine.

The foliage above and behind Sabine was lit by an industrial floodlight which sat at Constantine’s feet and pointed directly at her head. There was no time to disperse the insects or style the lemons. There was no time at all. Her bushy, bleached eyebrows and tall, plump body were in the process of becoming art.

Sabine shifted through a series of poses, tossing her hair, angling her arms, opening her mouth, and tilting her head back, while Constantine moved around the garden capturing her.

“I’m getting sexual art alien. I’m getting a revolution in a body. I’m getting pure genius,” said Constantine.

“What else?” said Sabine.

Constantine was shorter and more nuggety than her, with strong legs like a touring camel. He was quick and elegant, moving seamlessly through various squats and stretches as he photographed her. Sabine loved his salted, wiry hair, his defined cheekbones, and his soft paunch. She found her husband’s body irresistibly dense.

“You need to make sure I’m mysterious and powerful and surprised, but the portrait also needs to have the emotional impact of Rip my heart out You Fucking Cunt by Tracey Emin.” She motioned for Constantine to stop and went over to him, scrolling through her Instagram feed, angling the phone screen towards him as she rolled through reels of pictures.

“Am I framing it wrong? Should I reattach the camera to the tripod?” Constantine held her four-thousand-dollar camera in three fingers of one hand, the strap twisting in the breeze.

“Pure, uncompromising rigour is needed to make transcendent, supernatural art,” said Sabine.

“Hear! Hear!” said Constantine.

She returned to the tree, flapped her coat out behind her, and let the light blanch her white skin to ghost.

Constantine held down the shutter button and let more photos accumulate.

“I am impregnating every image with my unruly, creative juju. Are you getting my full body in?” said Sabine.

“You’re stunning,” said Constantine. He zoomed in. “The shoes?” said Sabine.

“Devastating,” said Constantine. He pointed the camera at her shoes and took a photograph, just of them.

“The eyes?” said Sabine.

“Perfect, in an unexpected way,” said Constantine.

Sabine’s upcoming exhibition, titled Fuck You, Help Me, in simple terms, was fifteen photographic portraits of her swinging naked from things outside at night and one short film; in more complex terms, it was something about discomfort and vulnerability and archetypes. Something, Sabine was sure, about juxtaposition. In each photograph she was covered from head to toe in sheer costumes. These wearable puppets, several feet long and made from panels of stretch silk, featured silicone faces that Sabine could position over her own. Think of the collection as: blinding flashes of light across a defiant, nude cis-female body. Think: a backdrop of forbidden, murky urban nightscapes.

“Sabine, you need to breathe,” said Constantine.

Their usual ritual on Monday nights was for Sabine to burn two salmon fillets, and for Constantine to insist they were delicious. He would swoop in and happily eat his up, even though the blackened fish tasted truly carcinogenic. The other six nights of the week he worked as a chef at one of the busiest restaurants in the city. He returned home late, filthy and exhausted, and smelling of sautéed chicken hearts and ninety-dollar steak.

Constantine put down the camera and extended his hand, and when she took it, he drew her close. He danced her across the grass and then dipped his glorious, emotional, hardworking wife headfirst towards the worm farm until she was cradled in the crook of his arm. She rested there, silent, seeming to enjoy it. After a moment he eased her back to standing.

Constantine’s phone rang from his pocket. He held his hand over it, kissed Sabine briefly on the cheek, then entered the house, speaking softly into the phone receiver.

Inside, he slunk past the window, opened the fridge door, and burrowed through the crisper. He snapped leaves off a head of lettuce then leaned against the counter and crunched through them. He hung up the call, pulled a strip of beef jerky from a pantry jar, and ate it in two bites. Shook out a handful of smoked almonds, and tossed them into his mouth. He kept going, running a tablespoon through a block of unsalted butter and dipping it in the salt dish before putting it into his mouth. He took a sip of whisky from the bottle, and then another.

Sabine knew that none of her demands, from the impractical to the perfectionist, were new to Constantine. The last time he had assisted her was on the seven-minute short film to be featured in her exhibition. Worship Me began with her taking off her pants and sitting in a dish of animal blood, and ended with her squat-hopping, bare-arsed, along a line of puckered prosthetic lips made from acrylic resin. Sabine had roped Constantine into sourcing the blood through his restaurant’s suppliers. For twelve hours, he’d stored that bin bag of blood in the work fridge, and at the end of his shift he’d carried it home, on the bus. And when Sabine, over the following two weeks, kept unknotting the bag and emptying it slowly to rehearse with, he became so upset due to her defiance of all health and safety regulations that he’d threatened to pour it down the drain himself. Why not practise with water? he kept asking. The chef in me can’t stand to see all of this waste!

The temperature dropped and hail began to fall in streamers of white. The balls of ice scattered across the garden and bounced off the metal drains like coins. Sabine gathered the equipment under one arm and hurried inside.

She skirted the end of the leather sofa in their open-plan living room and walked up the hallway, past three double windows, to her studio. Their freestanding worker’s cottage was set back in a sulk from the main road. A deep foundational crack had recently formed in one wall, and Sabine traced it with a finger as she walked. Often at this time of night she was distracted from her work by the family of heavyset possums thumping across the roof, or the pneumatic tsss of buses braking as they pulled into the stop by the front gate. But for now, only occasional thunderclaps interrupted the torrential hail.

Sabine placed her gear next to a pile of prosthetic noses and ears that looked like a cubist Greek chorus emerging from the wood of her desk. Behind her hung the gothic skins, each of them made to look like alternate versions of herself. Sabine kept all eighty of them clipped to hooks by the back of their necks, their heavy prosthetic-laden faces tipped away from the walls like pissed bel canto singers. Her own valley of the uncanny. Sabine would have preferred to drape her art around the house, but the puppets unnerved Constantine. The fluttering eyes and retractable tongues, and the amount of long hair that she hand-stitched onto their soft, loose heads, were too much for him. Once, during an argument, he had referred to them as snakes in wigs. Sabine had tried to explain to Constantine that the skins weren’t her but they were also very much her. She liked to bring them out for photo shoots then leave them for a while, either stuffed with pillows and propped up at the dining table or lying on the bed, but Constantine would gather them up and drag them back to her studio. It took every ounce of self-control for Sabine not to follow him in her overalls and bra, fighting him like a dog. She would never disrespect his knives like that.

Sabine uploaded the memory card from her camera to her laptop, then double-clicked on the folder and leaned forward. Her breathing slowed. She looked at each portrait with the intensity of a new mother. The floodlight had worked. Her face looked eerie and possessed. She relaxed. They were good.

She squinted. Were they good?

Sabine scrolled to the beginning to look through them again. The photos were excellent. Her promotional photos would be somewhere among them. She relaxed her shoulders. Bones somewhere in her upper skeleton clicked.

Art, Sabine tweeted, is my life. There was so much more to say but that would do for now.

As the hail momentarily eased, Sabine closed down her computer and joined Constantine in the kitchen. She took a large sip of his whisky then raised the bottle towards him.

“To art,” said Sabine.

“To both our careers,” said Constantine.

“And to us,” Sabine added. She took another drink then stoppered the bottle.

With a mouth full of the smoky brine, Sabine approached her husband, cupped his face with her hands, and brought his mouth to hers. She kissed him. A dank and grateful peat-bog single-cask kiss that she hoped would act like a drawstring, cinching them together. She wanted to be encased by his thick arms. She wanted nothing more than for Constantine to meet her with his own open-lotus heart. She lingered near him. Constantine stepped back. Again, his phone rang and he left the kitchen to take another call from the restaurant.

Sabine wasn’t hungry. She stacked the cups and plates in the dishwasher, grounding herself in a mundane task. Being domestic was necessary to fuel creativity, as was being strategic, but no one ever wanted to speak to a female artist about these things. Sabine wiped down the kitchen counter in big wet arcs, then squeezed out the sponge until her fist shook and mottled.

In bed, Sabine traced a line down Constantine’s spine, from the base of his neck to the top of his tailbone. She mapped each rib that connected to his back and stretched over his side. She missed him. Recently they had both been on a roll of late nights and early mornings. Sabine would not have been surprised if a psychic had told her that the elusive golden goose of success had gobbled them both down, and now she and Constantine were being pushed out, two shiny eggs of capitalist glory. The consequences of his recent promotion to head chef confused Sabine. It was as if his stress had tripled in size. Instead of being gone the usual fifty to sixty hours a week, he was away much longer. Eighty hours a week? One hundred?

Like a mountain climber approaching the summit, she needed three points of contact with her husband at all times. She needed hours of open-ended discussions about intimacy. Let him name in perfect detail all the ways they could twist together. Lambrusco evenings. Genital gazing.

Constantine twitched away from her finger and Sabine folded her hand back and tucked it under her pillow. It would also not surprise her if a psychic told her that she had known her husband in a past life in which they had been feuding lords. There was a sense of ancient tension and mistrust between them. Sabine rested her forehead on her husband’s back.

“Your emotional support is my lifeline during the lead-up to my exhibitions. But our closeness fluctuates, do you agree?” said Sabine. “Do you feel it come and go?”

Constantine nodded. “I feel it.”

Sabine narrowed her eyes. “But what do you feel?”

“Mainly, I just feel that I love you,” said Constantine.

“Yes, me too,” she said. “But soulmate connection, mutual awareness, hourly commitments to synchronicity . . .”

Constantine rolled onto his back and looked at the ceiling.

“Where do you physically feel my love the most? Where is it located in your body?” said Sabine.

“Probably my chest?” said Constantine.

As Sabine repositioned so that her head rested on his chest, she acknowledged silently to herself, and then aloud, that the audience might hate her exhibition. She envisioned being dropped by the Goethe and Constantine having to financially support her. She would have to spend the next season of her life finding some new profession. Sabine had looked up how long it would take to become an archaeologist, or a lecturer, or an electrician. Six years in most cases. She would be forty-four. Sabine forced herself to visualise an applauding audience.

She mentally turned up the volume of the crowd until she was being aggressively cheered. Her exhibition would sell out within half an hour of opening. Maybe even less. She imagined placing each cadmium-red sold sticker onto the wall beside her artwork. She imagined people grabbing her by the shoulders and shaking her, and calling her work wildly engaging. She rolled onto her stomach and flattened her palms against the mattress, but the tug of gravity sickened her. She flipped over and coughed.

“Sabine,” said Constantine, in a tone that told her to stop the nocturnal Cossack dance. He rolled around to face her, put a hand on her shoulder, and held her still.

“Talk to me,” he said.

“I father the work and then the public mothers it. Do I want them to be kind and understanding mothers? Sure, a little. Do I want to immediately fill the space I now have spare in my life with fathering more work to maintain career momentum? Not really, but thinking like this is—oh my fucking god.” Sabine covered her face with her hands.

“Every person who sees my exhibition is going to have an opinion about it,” she moaned. He underestimated how tender she became. Like a piece of sous vide meat, she was extremely softened by the process. The closer the time came for her work to be in the world, the more life force drained out of her in anticipation.

To encourage her to breathe, Constantine asked her to sing to him, but she wanted to know if he thought the puppet skins were interesting and complex, even though she had been making them for the last ten years. Were they still freakishly alluring and current? And, aside from his issue with the procurement of blood, what did he think of the film concept? The film title? Should she pivot entirely to making films? Her whole being registered the devastating anxiety of potential rejection. Raw. Embryonic. Vulnerable. The agony, the pure—

“Sing to me,” he said. Sabine dutifully sang the first few lines of “Auld Lang Syne,” and when she got to the end of the parts she remembered, Constantine asked her to start again, and she did.

__________________________________

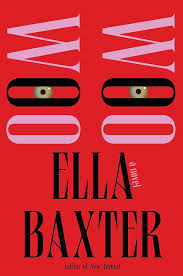

From Woo Woo by Ella Baxter. Used with permission of the publisher, Catapult. Copyright © 2024 by Ella Baxter.