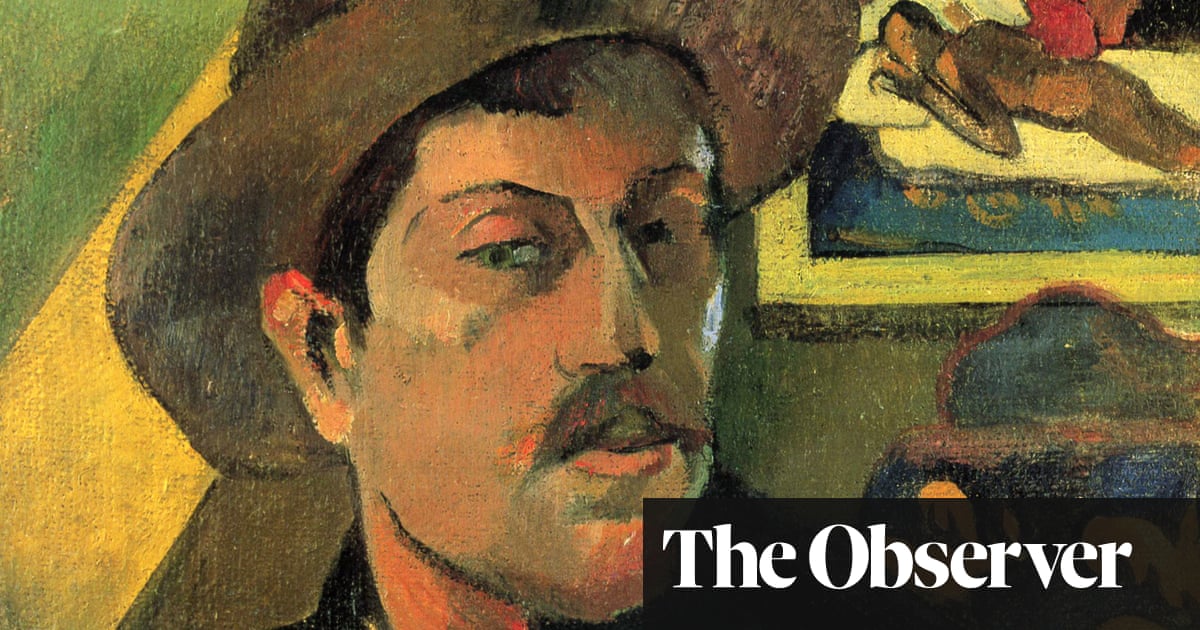

Sue Prideaux begins her biography of Paul Gauguin with an account of his long-lost teeth. Four of them were discovered in the year 2000 in a well near the site of his last bamboo hut in French Polynesia. The artist had secreted them there in a jar, for whatever reason, and investigation by the Human Genome Project proved them to be his. It was thought that the teeth might also offer conclusive evidence for the popular belief that Gauguin had been “the bad boy who spread syphilis around the South Seas”. But no trace of any treatments for the disease, arsenic or mercury, were discovered. “What other myths,” Prideaux asks, as she embarks on her reassessment of his life, “might we be holding on to?”

Prideaux is drawn to wild men as a writer; her previous biographies include award-winning lives of Edvard Munch and Friedrich Nietzsche. She has been helped in this project by the discovery in 2020 of a 213-page manuscript, Avant et après, handwritten by Gauguin during his last desperate two years in the Marquesas islands. It complicates the settled caricature of Gauguin as a sort of diehard libertine; instead, for example, detailing the importance of a string of legal battles he stubbornly fought on behalf of local Polynesian people in the French colonial courts.

Gauguin always felt himself born to that task. His childhood was shaped by two powerful women. His grandmother, Flora Tristan, admired by Karl Marx, survived attempted murder by her abusive husband (the bullet remained lodged near her heart) to become a famous pioneer of women’s suffrage. His mother, Aline, widowed on a voyage to Peru to claim her family inheritance, heroically dodged the advances of her great-uncle in Lima, while Gauguin enjoyed a wild “Rousseauian childhood” on the family estate.

after newsletter promotion

As a young man back in Paris, Gauguin showed no interest in art; he pursued a successful career as a stockbroker, until he lost his job after the banking crash in 1882. He had first picked up a pencil and started to draw when his young Danish wife, Mette, fell pregnant in the weeks after they were married. Unemployed, his hobby became his obsession. The family moved to Denmark to save money, but Gauguin had by then become a mostly sober guest around the raucous bar tables of the impressionists in Paris, returning home to Mette when his fellow artists ended their drunken evenings in the city’s brothels.

With a growing family, however, and no prospect of an income, his solution was to escape, first to Brittany, in search of midlife wildness. “You have to remember,” he wrote to Mette, “that I have two natures, the savage and the sensitive. I am putting the sensitive on hold, to enable the savage to advance, unimpeded.” Her response is not noted. His much more characteristic painting in Brittany was further liberated after an ill-fated job with the Panama Canal construction company; en route home he stopped in Martinique, where he suffered malaria, dysentery and hepatitis, but found a way to paint that brought him fully alive.

Some of those Martinique paintings were bought by Theo van Gogh, whose brother, Vincent, became a fervent admirer of Gauguin’s otherworldly light and colour. In Prideaux’s retelling here of Gauguin’s fateful stay with Vincent in Arles in 1888, you get a sense of the unease the painter must have felt when he arrived to discover that Van Gogh had adorned his bedroom with multiple giant sunflower canvases, and that he had purchased 12 rush-bottomed chairs on which he imagined their (as yet unidentified) disciples might sit. “Tired from the train ride, punch drunk from the colour overload … Gauguin coped badly,” Prideaux writes. When, after nine insane and creative weeks, Gauguin announced he was leaving – Van Gogh had lately hurled an absinthe glass at him, and come at him with a razor – he discovered that his friend had used that same razor to remove his ear.

In his own last, tormented years, suffering from intense ongoing pain from a leg mangled in a bar fight, advancing blindness and morphine addiction, Gauguin, it seems, dwelt more and more on those weeks with Van Gogh. In Polynesia, he sent back to France for some sunflower seeds for his tropical garden.

He was 42 when he left for Tahiti, with promises to Mette and his five children that he would make his fortune and return home. For nearly all of the remaining dozen years of his life, however, he remained in restless search of the paradises that his painting yearned for. Those years present the contemporary curator or biographer with a dilemma. On the one hand, the paintings that Gauguin made make him, arguably, the prime mover in that contemporary effort to “decolonise” the gallery – overturning as they did neoclassical and “western” ideals of beauty, advancing the cause of Indigenous populations. At the same time, for those who would wish to apply moral judgments to the past, the painter took a series of barely pubescent “wives” and lovers as enthusiastic muses in his project. Prideaux examines the facts and contexts of the painter’s South Sea life in greater detail than before, while refusing to begin to judge any of those choices. At times – for example, when the reader is invited to empathise with the depth of the painter’s grief on hearing news of the death of his young daughter, Aline, whom he had chosen hardly to see or support for a dozen years – you may wonder if just a little more critical irony is required. But Prideaux lets him construct his own epitaph: “virtue, good, evil are nothing but words, unless one takes them apart in order to build something with them”, Gauguin noted in his valedictory memoir, and he seemed to believe that right up to his lonely end.