Today, on what would have been Zora Neale Hurston’s 134th birthday, a posthumous novel by the American writer and cultural anthropologist has been published. The Life of Herod the Great, which Hurston was working on when she died in 1960, is a sequel to her 1939 novel Moses, Man of the Mountain, and up until now has been accessible only to scholars. As readers get their hands on this final work, writer Colin Grant takes the opportunity to look back at some of the gems in Hurston’s long and varied career.

The entry point

Zora Neale Hurston’s 1935 book of folklore, Mules and Men, was praised as the work of “a young Negro woman with a college education [who] has invited the outside world to listen in while her own people are being as natural as they can never be when white folks are literally present.”

Though her first work had been published a decade earlier, there’s still a sense of urgency in Mules and Men; she’s a writer in a hurry as she returns to the place of her upbringing in the south to gather folk tales such as those about Br’er Rabbit and Br’er Bear, and to “set them down before it’s too late”.

As a young writer Hurston already demonstrates a determination to plough her own path as a participating observer. She could see herself in her subjects because she had “the spy-glass of anthropology to look through”.

If you want to get to know the author

“I have been in sorrow’s kitchen and licked out all the pots.” Hurston’s description of her eventful life resounds through her memoir Dust Tracks on a Road. Raised in the “pure Negro town” of Eatonville, Florida, Hurston recalls how her happy childhood, along with those of seven siblings, came to an abrupt end aged 13, when her mother died.

The book is a sad but inspiring tale of resilience that speaks to the author’s indomitable spirit. After she flees her resentful stepmother, the narrative charts her many hardships and a succession of menial jobs. Hurston mined those experiences in her sharp and insightful writing in the exciting heyday of the Harlem Renaissance when, as the poet Langston Hughes writes, “the Negro was in vogue”. The privations of her childhood and adolescence also informed her empathic approach, conjured in this book, towards the subjects of the anthropological work of the 1930s Federal Writers’ Project in the backwash of the Great Depression.

The one to take on a long journey

As a trained anthropologist, Hurston often travelled by herself, much to the dismay of her colleagues. But when heading back down to the south in the US, among populations terrorised by the Ku Klux Klan, she considered it prudent to pack a pistol along with her notepads.

Funding from a Guggenheim fellowship allowed her to travel to Jamaica and Haiti in 1936 and 1937 to “investigate [their] folklore and native customs”, a trip that resulted in the travelogue Tell My Horse. Hurston’s accounts of wild pig hunts intrigued readers but the veracity of encounters with zombies (backed by photographic evidence) was contested by contemporaries such as Alain Locke, the doyen of the Harlem Renaissance, who dismissed them as “anthropological gossip”.

At times prurient and voyeuristic, the book can be a challenge to the reader but ultimately it shows Hurston, undeniably an idiosyncratic author, to be a sensitive chronicler of other people’s lives.

The classic

Hurston revelled in mischief and provocation. She invests that spirit in her protagonists too, who sometimes seem like versions of herself, and that makes her fiction thrilling to read. In Their Eyes Were Watching God, her heroine, Janie (who, like Hurston, marries three times), was inspired by voodoo mythology, in particular the legend of Erzulie. Janie channels the Haitian spirit of love and passion, a beautiful woman of desire who can never be loved enough and is trapped in an endless cycle of yearning and seduction.

Central to this fable-like novel is Nanny, the formerly enslaved grandmother of Janie who thinks black women are seen as “de mule uh de world.” Janie is a romancer and dreamer, and the book questions whether she can ever outpace this fate. She refuses to play the role expected of her, regardless of the danger she faces because of this. I struggled to locate the emotion at the heart of Their Eyes Were Watching God when I first picked it up a dozen years ago; it appears clearer now on a second reading that, although Janie is pitiable, the novel is infused with joy.

after newsletter promotion

Hurston has created a remarkable protagonist who is nobody’s mule and whose dreams will not be deferred, seeming to herald the rebellious heroines of the civil rights era 30 years later.

If you’re in a rush

The history of slavery in the US is a 246-year-old tragedy and its after-effect is a legacy of shame for black and white people. To minimise the stain, some African Americans claimed complicated ancestry, a stance mocked by Hurston when she wrote: “I am the only Negro in the United States whose grandfather on the mother’s side was not an Indian chief.”

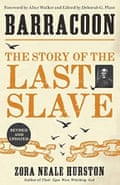

In 1928, Hurston travelled to Alabama in search of Cudjo Lewis, born Oluale Kossola, an 86-year-old man then believed to have been the last living abducted African to have been on the final slave ship to the US; the last “Black Cargo”, who embodied the tragedy and legacy of enslavement.

Hurston totally immersed herself in Kossola’s life and the book that came from her many interviews with him, Barracoon, is a heart-rending tale of loss and trauma. It’s also an engrossing account of Hurston’s friendship with Kossola, who hoped that her engagement would be an opportunity for him to reconnect with his lost tribe in Africa. Hurston didn’t have the heart to tell him that they’d all probably been wiped out by those who sold him into slavery. Published posthumously just six years ago, this slim but affecting book is a jewel.

The gut punch

Enslaved African Americans in the US adopted a canny strategy of resistance in dealing with their enslavers by “hitting a straight lick with a crooked stick”, that is, by presenting a non-threatening appearance in order to survive. Hurston defined it as “making a way out of no-way.”

The 21 short stories of love and hate in Hurston’s Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick are inflected with the grammar and idioms of African American folk culture. The tales, which shock and delight, reflect the changing demographic caused by the great migration of millions of southerners to the north, spurred on by “boweevil in the cotton and the devil in the white man.”

At times you’ll rush to turn the page and at others you’ll hold back, steeling yourself for the next wounding and brutal encounter. The book includes eight of Hurston’s “lost” Harlem stories from overlooked periodicals and archives. They highlight her fierce humour and offer a not-to-be-missed chance, in one volume, to listen in, diving into the richness of her satirical writing.