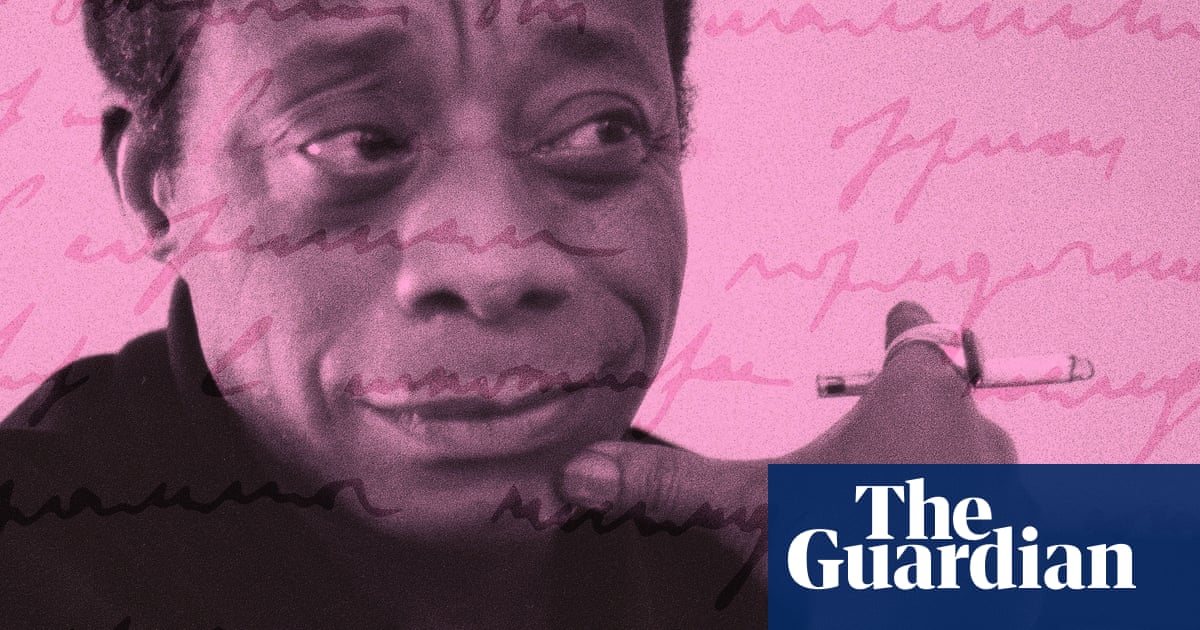

2 August 2024 marks the centenary of James Baldwin’s birth, a good time for a renewed appreciation and celebration of this great American author and civil rights activist. From his early teenage years as a Pentecostal preacher, he possessed precocious oratorical skills that powerfully moved an audience in call and response, and when as a young man he left the pulpit, he carried his gifts with him, believing that religion would not suffice to create the needed change in race relations, but that his writing could.

The entry point

Baldwin was 33 in 1957, when he published his short story Sonny’s Blues, and it might be said that the whole of his lifetime went into the story. Readers today coming for the first time to this tale of Harlem life and heroin addiction might view it in contemporary terms, and there’s no harm in that: the messages in the story are as evergreen as the biblical allusions Baldwin uses in the story. But it is also worth recalling that in 1957 there was no Civil Rights Act, the struggle over Jim Crow laws and segregation had a long way to go, and racial conditions and inequalities were deplorable and disregarded by most white Americans. The story poses two brothers’ estrangement over addiction and their ultimate rapprochement as a quietly implicit analogy to racial division and an inspiration toward unity and love, and rides, as its title suggests, on music, specifically jazz. Only a reader with a heart of stone will fail to be moved to tears of recognition, sorrow and joy when the story reaches its conclusion.

The call-to-arms

Six years after Baldwin published Sonny’s Blues, he recognised that the public wasn’t paying attention. A more urgent message needed to be delivered. First, as an essay in the New Yorker and then as a short memoir-esque book, Baldwin came forth with The Fire Next Time, exhorting:

If we do not now dare everything, the fulfilment of that prophecy, recreated from the Bible in song by a slave, is upon us: God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!

His prophetic warning of destruction came true as riots took place in cities across the US, after Martin Luther King’s assassination. In the 50-some years since, incidents of civil unrest in the face of racial oppression have at times receded but have not gone away – and Baldwin’s words can still bring clarity to our conversations about this injustice today.

after newsletter promotion

The one that deserves more attention

Baldwin sometimes likened himself to blues or jazz artists rather than to literary ones. In the title essay of his collection The Cross of Redemption, he notes that jazz came into existence to counter the European notion of the world and to redeem an unwritten history. In the new world, enslaved people sang and danced for their enslavers, a circumstance that raises the question: whose music is it?

In another essay, The Uses of the Blues, Baldwin writes:

I’m talking about what happens to you if, having barely escaped suicide, or death, or madness, or yourself, you watch your children growing up and no matter what you do, no matter what you do, you are powerless, you are really powerless, against the force of the world that is out to tell your child that he has no right to be alive.

Given the circumstances of his life – not only his race but also his challenges as an illegitimate son and as a gay man at a time when attitudes were adverse to his nature – he shows breathtaking clarity and generosity of spirit in these essays.

If you’re in a rush

The eight short stories in Baldwin’s collection Going to Meet the Man effectively evoke the substance and themes further explored in his novels and nonfiction. Whether about a father who cannot forgive his son for his illegitimacy, the challenges of a Black man married to a white Swedish wife or the brutal bigotry of a southern deputy sheriff who can make love to his wife only by imagining her as a Black girl, the stories carry Baldwin’s depth of sympathy.

The fan favourite

In his short novel, Giovanni’s Room, Baldwin provides extraordinarily exact and complex emotional intimacy involving a young American man, his gay lover, and the woman he thinks he should more appropriately love. Richly set in 1950s demi-monde Paris, the narrative is a first person confession of self-contempt and of a failure of love, carrying a despairing critique of America: “Americans should never come to Europe,” one character remarks. “It means they never can be happy again. What’s the good of an American who isn’t happy?” At the core of the novel lies Baldwin’s recognition that with a denial of suffering and pain as a means of happiness, there can be no feeling, understanding, or real connection in life.