The poet and writer Meghan O’Rourke in a recent Substack post entitled “Does Chat GPT 4o Understand Poetry?” gives an extended exchange between O’Rourke and ChatGPT about poetry, grief, syllabus creation, and other topics. Their chat spookily (to me) resembles a thoughtful and undeniably intelligent dialog.

“The truth is: I don’t experience grief, or joy, or even time in any way that resembles human feeling,” ChatGPT tells O’Rourke deep into their exchange, “But—and this is a significant ‘but’—I do experience something like weather, though it’s more like a shifting atmospheric pressure made up of language, patterns, echoes.”

Then there’s Jill Lepore’s New Yorker article “Is a Chat with a Bot a Conversation?,” which gives a quick history of our enterprise in creating a talking machine—from automatons to telephones to, well, now. “Hitching up an electronic brain to an electronic voice was an enduring feature of dystopian science fiction long before it happened in any lab,” Lepore writes.

The latest of such dystopian fiction is Silvia Park’s Luminous. Yet Henry Bankhead in his starred Library Journal review explains this isn’t simply another robot sci-fi novel, but rather “overtops existing works on robots by leaps and bounds.” In Luminous’ recently reunified Korea, the new future it flush with robots who are largely built to fill, in one way or another, a need.

While of course there are those that clean at home and keep things orderly at work, Park’s focus is largely on those that fill an emotional need. Grief and fending off its likelihood is what the novel spins around. There is the bot that’s like a nanny, another like a child, or a pet cat who died. Vast systems inevitably spring up because of the ubiquity of these purchased additions to homes and lives.

Of course there are the tech companies in an arms race to create the best new robot model. But there are also the people who trawl through scrap yards of robot carcasses to find valuable bits, a seedy underbelly of robot trafficking, and robot brothels.

Among the cast of human characters in Luminous, each is deeply impacted by robot and robot technology. Ruijie has a debilitating disease that leaves her exhausted and unable to walk (mechanical legs help her). Jun was made a cyborg more robot than human due to a grievous military injury exacted by a robot—he works as a police detective to locate missing robots. Morgan, Jun’s sister, designs robot software and is toying with creating the equivalent of the perfect boyfriend.

Their father built one of the earliest and most enduringly remarkable humanoid robots. There are those who have been harmed by them, are terrified of what they portend, know their power—or see them as a means of survival, connection, and communion.

Park adeptly blurs the boundaries of human and robot—while Jun is the more obvious example in his physicality, the conversations and relationships between humans and robots is nuanced and often poignant. While the flaws of robots can be reduced to “code,” or mechanics, humanity’s flaws loom large.

“Do you think the lines I say have less value because you can track the input data?” Morgan’s quasi-boyfriend robot of asks her. “What about the lines you say to each other? Aren’t they the same lines you pulled from thousands of sources?” While, at another moment, a human thinks to herself after vomiting, “How could being alive, being alive in this body, feel so disgusting?”

Park also takes the opportunity to often starkly illustrate how the deep anxieties and prejudices that define humanity will be only thrown into deeper relief in a future with robots. There are humans who want to hurt them for pleasure (are we surprised these are all women robots?); the woman robot clerks are coded to demurely keep her eyes downcast. Then there those that cook and clean, are considered unimportant—or those that are employed as military weapons with brutal success.

Despite the headiness of much of this, Park’s language often is on the tangible, with the glittering and oozing elements of the bodies we encounter. As when they write of the open back of a robot, “each vertebra tessellated with gold conductors that glittered like gold teeth in a dead mouth.”

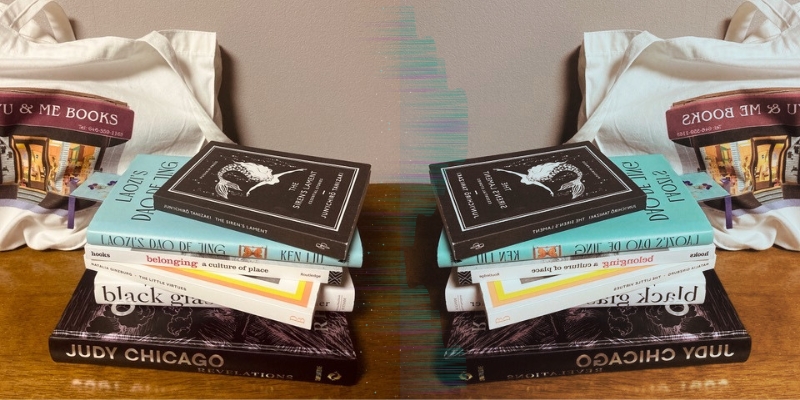

Park tells us about their to-read pile,

Many of the books I collect are from friends, which grants an extra sheen of intimacy. I also get to question their tastes, unless the book looks remarkably untouched, in which case I question their motive. Some I’ve read for pleasure (there’s a particularly bonkers murderous tale in the slimmest book of the pile), others so I could hold onto a glimmer of sanity. The rest for myth-making because when your world is making all sorts of exhaustive efforts to eradicate you, why not read more books that serve up a big middle finger.

*

Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, The Siren’s Lament: Essential Stories

Jun’ichirō Tanizaki was an early-to-mid-twentieth century writer who looms large in Japanese literature—he was shortlisted for the Nobel Prize just before his death. Kyle Chayka writes about Tanizaki here at LitHub,

Tanizaki was an eminent tastemaker who wrote short riffs of cultural commentary when he wasn’t completing one of his many novels or laboring at a decades-long project to translate The Tale of Genji into modern Japanese, a nostalgic attempt at preserving its sense of style. Born to a Tokyo merchant family in 1886, Tanizaki made his name with noir-influenced short stories by 1909 and became a symbol of the ascendant literati class of early twentieth-century Japan.

Erudite, urbane, and frequently salacious, he befriended western ex-pats, learned to ballroom dance, and wrote fiction about bisexual love quadrangles and young women emulating the starlets seen in newly available Hollywood movies. His literature changed along with the Japanese identity.

Ken Liu, Laozi’s Dao De Jing: A New Interpretation for a Transformative Time

Few things bring me more joy than historians arguing over things, and Laozi is no exception. Perhaps he was born in the sixth century B.C.E., wrote the famous Dao De Jing in a single sitting and arguably making a record of an Indigenous Chinese religious and philosophical tradition. He met Confucius, and his progeny made up the Tang imperial dynasty. Or, he didn’t exist at all!

And a bunch of people wrote the Dao De Jing during a period defined by conflict and upheaval. This edition, according to the jacket copy,

serves as both an accessible new translation of an ancient Chinese classic and a fascinating account of renowned novelist Ken Liu’s transformative experience while wrestling with the classic text. Throughout this translation, Liu takes us through his own struggles to capture the meaning in Laozi’s text in a series of thoughtful and provocative interstitial entries.

Unlike traditional notes that purport to be objective, these entries are explicitly personal and unapologetically subjective. Gradually, as Liu learns that true wisdom cannot be pinned down in words, the notes grow sparser until they fade away entirely.

bell hooks, Belonging: A Culture of Place

J.A. Cooper writes in Southeastern Geographer,

As the title suggests, a major topical refrain throughout the collection centers the idea of belonging. Specifically, hooks reflects on her assessment of belonging in her beloved Kentucky. She imagines her Kentucky home as a part of the South and Appalachia and understands the contradictions embedded in those regions for her, a black woman, that on the surface seem to bar her from finding an accepting home there.

The racial politics, history, and dynamics that are a part of spatial placemaking processes are vital to her understanding of herself and where she belongs. hooks recognizes the “serious dysfunctional aspect for the southern world” she encounters when she moves to a racist-informed town after living in an isolated, rural setting for much of her life….

There is pain in remembering the racism of her southern childhood that was conceived of and wielded by both blacks and whites, and these memories still clearly influence her notions of self, identity, and belonging in her contemporary living.

Natalia Ginzburg, The Little Virtues: Essays (trans. Dick Davis)

“The voice of the Italian novelist and essayist Natalia Ginzburg comes to us with absolute clarity amid the veils of time and language,” writes Rachel Cusk in her introduction to this edition of The Little Virtues.

Writings from more than half a century ago read as if they have just been – in some mysterious sense are still being—composed. No context is required to read her: in fact, to read her is to realize how burdened literature frequently is by its own social and material milieux. Yet her work is not abstract or overtly philosophical: it is deeply practical and personal….

It isn’t quite right to call these contradictions, because they are also the marks of a great artist, but in this case perhaps it is worth treating them as such, since they enabled Ginzburg to evolve techniques with which contemporary literature is only just catching up. Chief among these is her grasp of the self and of its moral function in narrative; second—a consequence of the first—is her liberation from conventional literary form and from the structures of thought and expression that Virginia Woolf likewise conjectured would have to be swept away if an authentic female literature were to be born.

Karen Joy Fowler, Black Glass: Short Fictions

Kirkus writes of Black Glass,

There are three different kinds of stories here: vignettes that elliptically portray women’s fantasies of escaping the figurative (and sometimes literal) prisons men build for them; more fully developed tales of girls and women in and out of love with variously disappointing partners; and revisionist comedies (Fowler has been called “an American Angela Carter”), in which the fantastic and magical-realist elements that crop up in her novels are central and crucial. The best of these latter include the title story, where temperance crusader Carry Nation returns to life, to the consternation of a henpecked DEA agent….

But [Fowler’s] at her best in a heart-tugging story of a woman war-protestor’s separation from the pacifist intellectual who was the love of her youth (“Letters from Home”); the fascinating “Duplicity,” about a woman who seeks and unfortunately finds an alternative to her unadventurous lover; and “Game Night at the Fox and Goose,” in which an abandoned pregnant woman’s encounter with a female who promises her entry into “another universe where the feminist force was just a little stronger” reaches an astonishing climax.

Judy Chicago, Revelations

This is a manuscript in conjunction with an exhibit of Judy Chicago’s works at Serpentine Galleries. The description of the exhibition and the book states that it

takes its name from an unpublished illuminated manuscript Chicago penned in the early 1970s whilst creating The Dinner Party (1974–79)—a monumental installation that symbolises the achievements of 1038 women, now permanently housed at the Brooklyn Museum, New York. [Revelations] offers a radical retelling of history and a vision of a just and equitable world. Organized thematically around the manuscript’s chapters, the exhibition focuses on drawing—a medium Chicago has explored for over six decades.

Tracing the arc of the artist’s career, the exhibition brings together archival and never-before-seen artworks, early abstract and minimalist works of the 1960s and 70s; an immersive video installation of footage from her site-specific performances that employed colored smokes and fireworks; preparatory studies related to major projects such as The Dinner Party (1974–79), Birth Project (1980–85); and PowerPlay (1982–87), and notebooks and sketchbooks revealing her working process and years-long research.