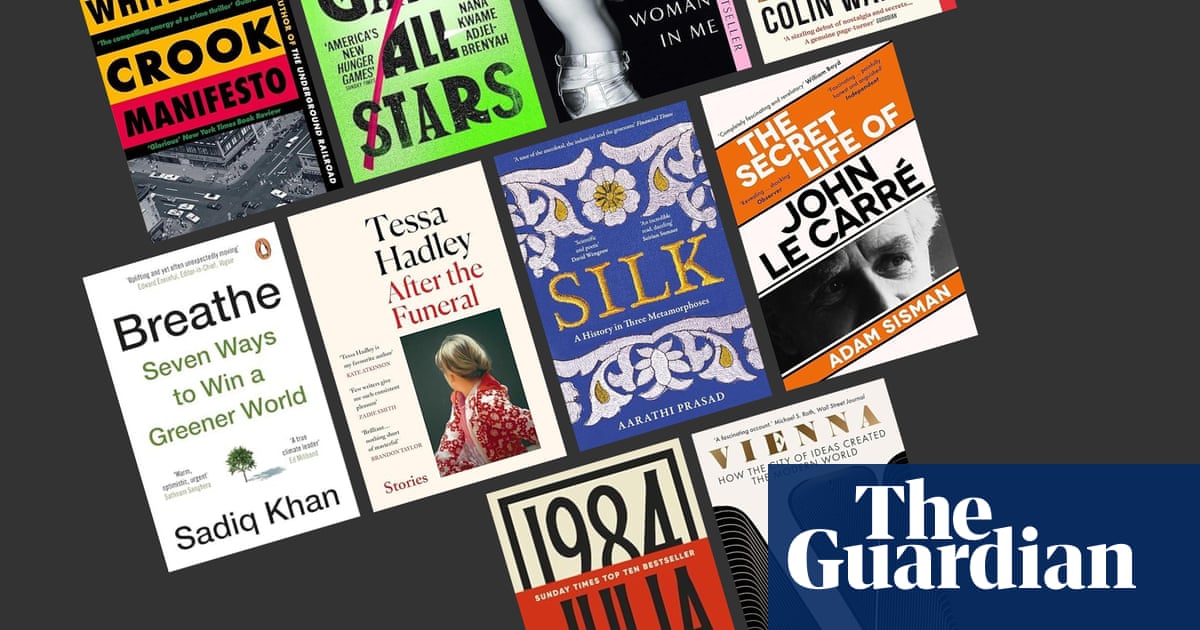

Vienna Richard Cockett

How this city shaped our modern world

According to the journalist and historian Richard Cockett, Vienna “lit the spark for most of Western intellectual and cultural life in the twentieth century”. From psychoanalysis (Freud) and nuclear fission (Lise Meitner), to the design of shopping malls (Victor Gruen) and fitted kitchens (Margarete Lihotzky), Viennese men and women played a crucial role in transforming the way we live and think.

Cockett argues that this was not just due to the golden age of Viennese cultural life in the years before the First World War, when the “sprawling, multiethnic, plurilingual” Austro-Hungarian empire was still ruled by Franz Joseph from Vienna’s beautiful Schönbrunn Palace. Rather he shows that the real key to Vienna’s influence stems from the lesser-known interwar period, when the city council undertook a “radically ambitious democratic experiment in human evolution”. At a time when the rest of Austria was turning to the far right, the socialist city became known as Red Vienna and produced “the last great flourishing of the city’s intellectual and cultural life”.

Thanks to its diverse population drawn from across the Austro-Hungarian empire (in 1910 about half the population was not born in Vienna), at the beginning of the twentieth century it was a uniquely dynamic and tolerant intellectual community: “to be brought up, to be educated and to work in Vienna was to share in a particular, unique, open and cosmopolitan environment.” But this same city was also home to Adolf Hitler and many of the divisive and anti-democratic ideas that shaped him were formed in his mind there before the First World War, in particular the opposition to Viennese liberalism.

In the interwar period however, Cockett argues that the critical rationalism that was the hallmark of Red Vienna’s intellectuals became the antithesis of fascism. From sociology to economics, Vienna’s evidence-led intellectuals believed their ideas should serve real people not ideology, opposed totalitarianism and embraced political pluralism.

The Viennese diaspora have proved to be astonishingly influential, across a wide range of fields. They include film directors, such as Otto Preminger and the “flamboyant, domineering” Fritz Lang, as well as actress Hedy Lamarr, who was also a talented inventor. In the war, she devised a frequency-hopping signal for torpedoes that was hard to jam, an invention that led to Bluetooth wireless communication. Among many outstanding Viennese architects was Richard Neutra, who from the 1920s became synonymous with the new American home and described his profession as “applied biology and psychological treatment”. Viennese émigrés also shaped modern British publishing, from Thames & Hudson, founded by Walter Neurath, to Weidenfeld & Nicolson, co-founded by George Weidenfeld, “Britain’s most famous and certainly best-connected, post-war publisher”.

Cockett’s highly original and informative study offers a remarkable insight into how the people of this diverse and liberal city helped create our modern world. As he rightly says, “we are all in their debt”.

PD Smith