In 2024 politics has been inescapable for many poets, a retreat from the world impossible, particularly from the Israel-Gaza war. This has been especially true for the Palestinian-American poet Fady Joudah, whose […] (Out-Spoken) suggests the impossibility of fully articulating the effect of the pain and destruction, but also a yawning absence now and in the future: “From time to time, language dies. / It is dying now. / Who is alive to speak it?” Meanwhile, in Bluff (Chatto & Windus) Danez Smith delivers an “anti poetica”, grounded in the protests after the murder of George Floyd, exploring the limits of poetry to effect real change.

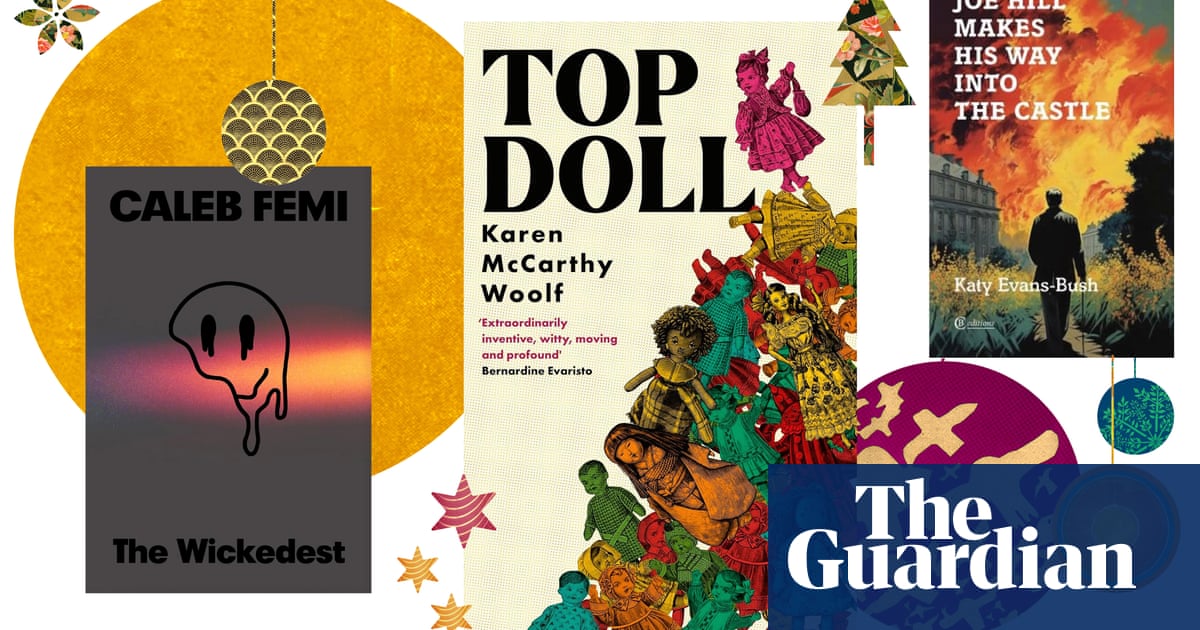

Rachael Allen’s second collection, God Complex (Faber), uses the twin poles of a relationship breakdown and environmental collapse to paint a picture of a crumbling Britain, where “sense slides into oblivion”. Joe Hill Makes His Way Into the Castle by Katy Evans-Bush (CB Editions) is focused in its anger. She refashions the words of American countercultural poet Kenneth Patchen, an inspiration of the Beats, into blasts against the depredations austerity has caused, while also finding redemption amid the chaos.

A number of poets experimented with novel-like narratives, daring in their structures and subject matter. Notable among these is Ella Frears’s Goodlord (Rough Trade Books), a book-length email to an estate agent that spirals into a hypercharged series of Prufrockian reminiscences about the horrible reality of renting in the 21st century: “These cursèd rooms, // they sap! they sap! they sap!” Top Doll by Karen McCarthy Woolf (Dialogue) is similarly playful; and by giving voice to the dolls in the collection of a reclusive billionaire, she smuggles in deep truths about feminism and slavery.

In a strong year for debut collections, two stood out in particular. Monster by Dzifa Benson (Bloodaxe) dazzles in its range, technique and imagination, while Camille Ralphs’s After You Were, I Am (Faber) brings a medieval spirituality vibrantly into the modern world.

On a melancholic note, British poetry lost some exceptional talents this year. John Burnside’s final collection, Ruin, Blossom (Jonathan Cape), brings typical acuity to an awareness of what is lost with time passing: “Let us remember / the stillborn: how they // cede their places here / with such good grace // that no one ever speaks of them // again.” Kathryn Bevis’s The Butterfly House (Seren) was written through a late-stage cancer diagnosis, and is vivid with sticky metaphors and plainspoken declarations of love.

The anthology I turned to most is Poems as Friends: The Poetry Exchange 10th Anniversary Anthology (Quercus), which collects 50 conversations from the popular podcast, suggesting how poems can provide comfort, wisdom and insights into how to live. It’s a beautiful tribute to the late Fiona Bennett, who came up with the idea and did so much to bring poetry to a wider audience.

Two of the UK’s most lauded poets delivered magnificent capstones to their careers. Both Wendy Cope’s and Mimi Khalvati’s Collected Poems (Faber and Carcanet, respectively) provide acres of proof of their brilliance, and their unique ability to turn language into lyric poems that beguile. I also enjoyed how Victoria Chang uses the paintings of Agnes Martin as a jumping-off point for her existential ruminations in the Forward prize-winning With My Back to the World (Little, Brown).

after newsletter promotion

Caleb Femi’s second collection, The Wickedest (4th Estate), confirms him as one of our best chroniclers of what it is like to live now. Over vignettes set in house parties, he communicates the urgency and vitality of finding community, bliss and joy through a hedonism keenly aware of its own short shelf life. His visual experience as a director shows in the precision of his images: “The light is pinstriped and scarce / but your eyes see everything: particles in the air – colliding nebulas, / the sandcastle in the centre of the dance. / One yout tells you that every grain contains / the memory of a night”.

This year also saw the posthumous publication of Adam (Faber), the first collection by Gboyega Odubanjo, who died in 2023. Inspired by the discovery of the body of a black boy in the River Thames, the poems form a chain of extended thoughts on what it is to belong – and whether that is even possible – when you come from “so far east it’s west to another man”. Blending English, Pidgin and Yoruba, Odubanjo’s language is by turns laser sharp, expansive and indelible: “there is nothing left to dig a grave / wait and enjoy life / wait and bury me / your touch is life / your gapped teeth please me / the story is yours”. Finishing the book leaves you mesmerised, and keening for what would have come next.

Rishi Dastidar’s latest collection is Neptune’s Projects (Nine Arches). To support the Guardian and Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.