Rupert Everett prefaces his suite of short stories with an account of the showbiz ruse that provides the title, a grim little routine whereby American film producers intoxicate a would-be screenwriter into feeling that a deal has been done, only to then forget them entirely. Will Everett’s readers offer up the English equivalent, murmuring “Darling, you were marvellous” before moving swiftly on? Well, the collection certainly delivers what Everett’s fans will be hoping for: quality time in his inimitable company. But it also delivers much more. Sometimes, it is simply the energy and poise of the prose that arrest one’s attention; often, it is Everett’s combination of studied carnality with an outlandish gift for invention. This is a storyteller unafraid to spike his black comedy with sudden and strongly brewed emotion – and vice versa.

In his frequent interjections, Everett is disarmingly frank about these stories’ origins. In 20 years of making pitches to TV and film producers, only one project of his has ever landed. This was his directorial debut, The Happy Prince, a meditation on Oscar Wilde’s fall from grace which got considerably more of Wilde’s rage and sorrow on to the screen than many more respectable versions (elements of the film are reworked in the second of these stories). But that was back in 2018, and these days, Everett’s phone isn’t ringing. A rainswept encounter with a former Soho contact sparks the idea that he could usefully bring some of his rejected ideas into a new kind of life. The result is intriguing, not least because these vivid little adventures aren’t really short stories at all; they are scenes from unmade films, reimagined as prose.

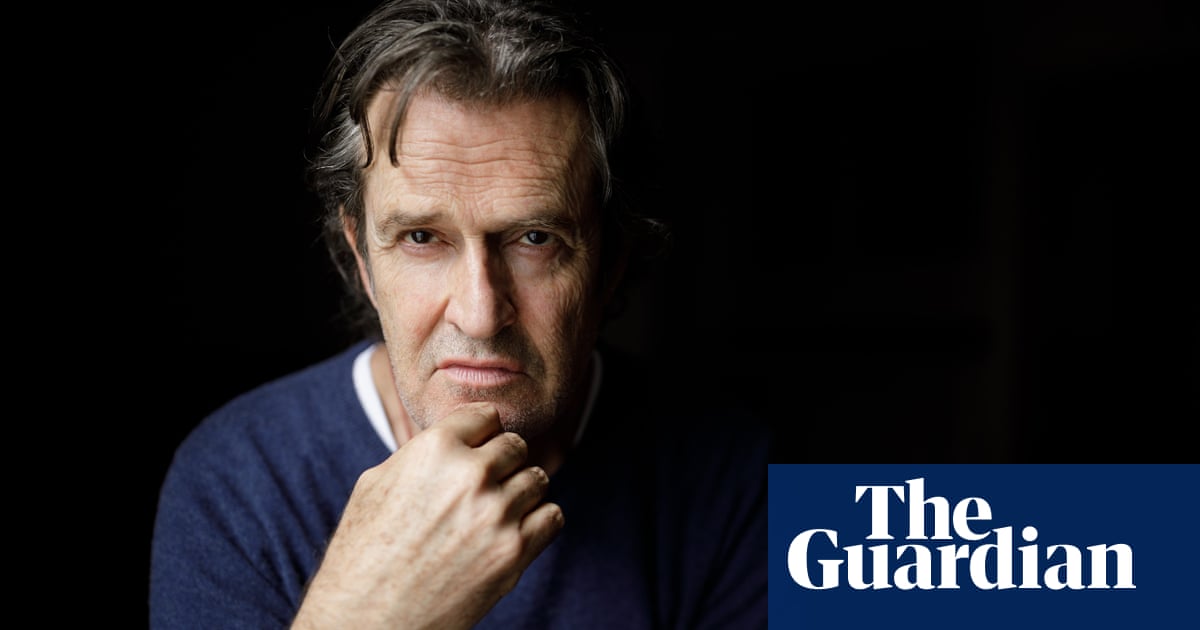

In the course of a career that started at the Glasgow Citizens theatre company and took him via the West End to Hollywood and beyond, Everett has been by turns an actor, a writer and a director. Here, he draws on all those different experiences. Whatever the setting, the dialogue is always sharp and telling. Sometimes the author plays himself; required to transform, he inhabits even the strangest of his fictional alter egos with assurance. The settings are realised with distinctively cinematic flair; they range from the backstreets of Wilde’s Paris to their Aids-era equivalents, from a ruined Anglo-Irish mansion to a heat-becalmed Suez canal. Their genres vary as much as the settings: one piece dishes the dirt on the underbelly of 1980s Hollywood with made-for-TV tastelessness; another documents a failed shipboard romance as the very best kind of costume drama, clear-eyed and memorable. Everett makes especially skilful use of cinema’s easy ability to filter its stories through screens of memory and flashback; only on rereading the collection do you notice that the intensity and colour of the storytelling almost always spring from the fact that everything is being played out in someone’s dreams, or memories or nightmares.

This becomes most explicit in the last story, which drops all pretence of transforming its material into short-form prose and is laid out as an actual film script. This piece, fascinatingly, is made out of just one episode’s worth of material intended for a TV series based on Proust’s À la Recherche du Temps Perdu. Instead of going for the elegant restraint of Harold Pinter’s version (also unproduced), this filleting and re-ordering of the granddaddy of all flashback narratives is lyrical and violent, unafraid of dwelling on Proust’s lust and cruelty as the dying author ransacks his memories for meaning. Episodes from Proust’s own life are woven into those of his novel, and the final sequences especially restore some much-needed sexual explicitness to this darkest of autofictions.

Individually, the stories are exhilarating; together, they add up to an intriguing self-portrait of an artist at work, presenting us with the multiple facets of an undaunted imagination, recut, repolished and ready to shine in the dark.

after newsletter promotion