Peter Mackay seems to write poetry as he speaks. An island, he ponders, “can be seen as bounded by the sea or as infinitely connected”. He is interested in the parallels between Federico García Lorca’s Andalucía and “the wet deserts of the outer Hebrides”. Poetry, he believes, “can create whole worlds and make them matter”.

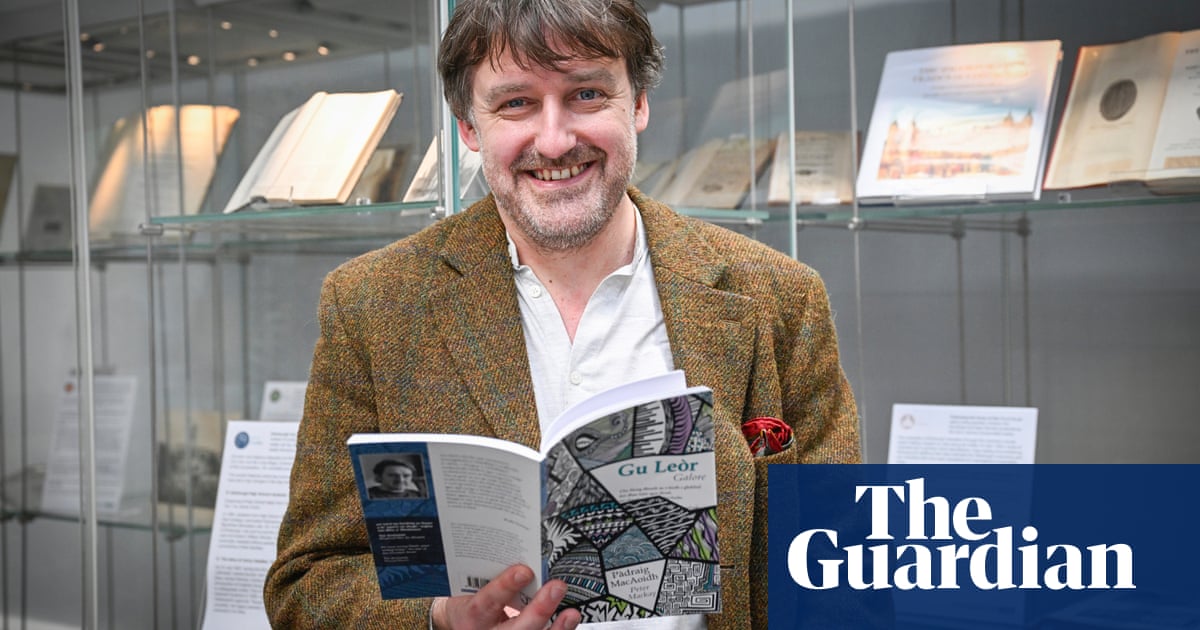

It is appropriate, then, that 45-year-old Mackay was announced yesterday as Scotland’s new makar, or national poet. He is the youngest makar to date, and the first one who writes primarily in Gaelic. He is “flabbergasted and delighted” by the honour, but also “slightly bemused,” he says.

“There are so many other great, distinctive voices who could do this role and who will go on to do it in future,” he says. “It’s a huge honour, especially considering those who have come before me” – previous makars include Jackie Kay and Edwin Morgan.

Mackay started life on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides, going on to study in Glasgow and Dublin, where he developed an interest in the links between Scottish and Irish literature. These days he divides his time between his role as senior lecturer in Literature at the University of St Andrews and writing his own poetry; his collections, 2015’s Gu Leòr/Galore, and Nàdar de/Some Kind of from 2020 were each shortlisted for the Saltire Scottish poetry book of the year.

While his first poems were published in a 2010 pamphlet, he started much earlier – a poem he wrote aged four can still be found filed safely away in his mother’s home. “I grew up in a community where there was so much music, so much song, so many stories,” Mackay says. “That meant it was always legitimate; I was allowed to write and to be a storyteller.”

Raised bilingual in Gaelic and English, Mackay also speaks Spanish, Danish and Irish, and the relationship of languages to each other and to culture more widely features heavily in both his work to date and his ambitions as makar. His poems usually begin life in Gaelic, after which he roughly translates them into English before the two diverge and grow apart – a process he describes as “necessarily dishonest translation” because, in a nod to Emily Dickinson, “every language tells its truth”.

His appointment comes amid a national conversation about the future of Scotland’s native languages, Gaelic and Scots, as the number of speakers of each dwindles. The Scottish languages bill, which would give both official status, will have its final reading during Mackay’s tenure.

“It’s useful to have a Gaelic speaker in the role for that, to contribute to discussions about all the different languages spoken in the country today, and to try and build as many bridges as possible between Gaelic, Scots, Polish, Urdu and all those other languages,” he says. “I’m interested in how Scotland has always been multilingual, and multilingual in ever-increasing and fun ways.”

Poetry can play a role in keeping endangered languages alive, he believes, by “pushing the boundaries of what can be done”.

“One of the dangers when a language is under threat is you get very conservative and say nothing can change, but these have to be living languages; they have to be able to evolve and change.”

But, he notes, that comes with its own responsibilities. “I’m somebody who is reluctant to take on the role of representing anybody else. I think it’s important symbolically that there is a Gaelic makar and I’m grateful and honoured that it’s me, but I do have a sense that everything I do is partly also representing Gaelic speakers and poets as well as my own work and merits – and that’s a lot of different hats to wear and people to do the best possible job for.”

The makar is tasked with promoting poetry across Scotland and producing work that responds to national moments. Mackay expects to engage with themes of climate and environment that characterised the tenure of his predecessor Kathleen Jamie – which is just as well because, he says, the Gaelic language is “landscape-heavy”.

after newsletter promotion

“I sometimes have a slightly annoyed voice in my head that says ‘there must be more themes than birds, weather, trees’… but it provides an opportunity to continue conversations about nature and the environment, and to see what we can learn between languages,” he says.

The 2026 Commonwealth Games, which will be hosted in Glasgow, provide another such chance to “talk about the world in different languages,” he believes. “Perhaps it’s ironic given the role, but I’m interested in looking beyond the national boundaries of poetry.”

It is an exciting time to become makar, 20 years after the role was established, says Mackay. “Poetry in Scotland is in a really solid and interesting place – the role has really placed it at the heart of Scottish public life, but the poetry culture has also changed in that time.

“Now there are slams, readings, different types of poetry – performance and social media alongside traditional forms which are encouraging whole new generations to become engaged in a different way. The makar allows for those conversations to happen but can also be an instigator for new ways of thinking about poetry.”

Does this mean we’ll be seeing the first TikTok makar? “I’d have to improve my TikTok game for that to happen,” he laughs. But in verbalising his feelings on the brink of his tenure, it’s a surprisingly modern wordsmith he reaches for.

“We’ll just have to see how the next couple of weeks and months go,” he says. “And – in the words of RuPaul – try not to fuck it up.”