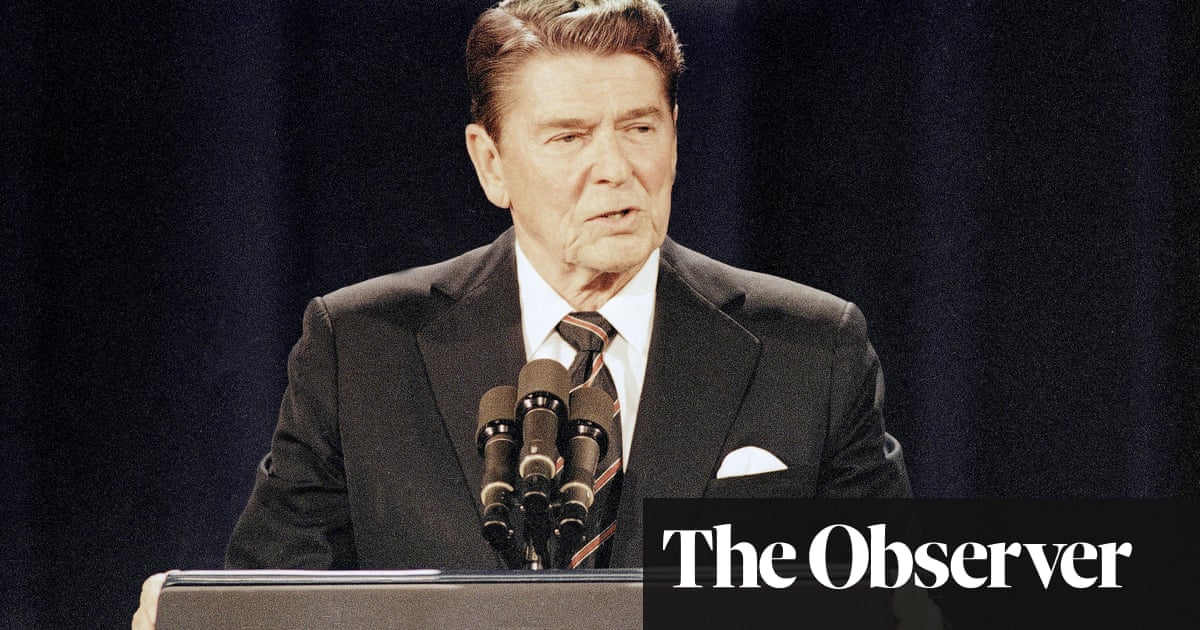

As we’re reminded every four years, the US, while purporting to be a republic, is more like an elective monarchy. Presidents campaign as partisans, but once inaugurated they’re expected to transcend politics; draped in the flag, their task is to exemplify the national character. Although nowadays the country is too fractious to be personified by any individual, in less schismatic times Ronald Reagan managed the feat – as American author Max Boot argues in his generous yet sharply perceptive biography – because he was “a mainstream, generic, nonhyphenated American, Midwestern born”. “Mr Norm is my alias,” Reagan said. “Average will do it.”

But was Reagan amiably bland or somehow blank? Boot finds him to be incapable of introspection, so emotionally withdrawn that he remained unknowable to everyone but his second wife Nancy, whom he called “Mommy”. While preaching “family values” Reagan neglected his offspring, and when his daughter complained he insisted: “We were happy, just look at the home movies,” relying on the camera to vouch for his parental affection. Although he was benevolent enough – as a teenage lifeguard at a lake in Illinois he saved 77 swimmers from drowning, and as governor of California he often sent personal cheques to citizens who wrote to him about their problems – Boot thinks that he had no real comprehension of other people. This limited his range as an actor; affable and superficial, in his Hollywood films he could only play versions of himself. It also explains what Boot regards as the most shaming failure of his presidency, which was his prudish refusal to confront the Aids epidemic.

Reagan grew up as a New Deal Democrat but acquired a horror of the welfare state during a few dreary weeks he spent filming in London in 1948. Socialism, so far as he understood it, consisted of drab, underlit shop windows and watery meals; complaining that the English “do to food what we did to the American Indian”, he exempted himself from rationed austerity by having steaks flown in from New York to be cooked at the Savoy. Otherwise, Boot suspects that he lacked ideological convictions, and his earlier careers as a radio announcer and a Hollywood contract player dictated his conduct after he graduated to politics. When he ran for re-election as president in 1984, he appointed his campaign manager as his director and compliantly recited whatever the Teleprompter told him to say.

Reagan performed with aplomb as head of state; he had little interest in serving as the nation’s chief executive, and relied on aides whom he called his “fellas” to articulate policies and implement them. Boot pays more attention to Washington intrigues than Reagan ever did, but his book is best when he looks away from backroom plotting. The account of John Hinckley’s assassination attempt in 1981 is alarming and also moving. Nearer to death than was disclosed at the time, Reagan put the panicked surgeons at their ease by making jokes; during his recovery in hospital he got down on his knees to clean up a mess in the bathroom, reluctant to delegate the dirty work to a nurse.

Boot gives crises an edge of wry amusement. Nuclear summits with the Russians were envenomed by Nancy Reagan’s reaction to the immaculately styled, intellectually haughty Raisa Gorbachev. “Who,” fumed the outclassed first lady, “does that dame think she is?” In an episode that threatened to topple Reagan, the gung-ho Colonel Oliver North was put in charge of illegally selling arms to Iran in exchange for American hostages, and travelled to Tehran with a chocolate cake as a token of his government’s goodwill. The bearded revolutionary guards, amused by American naivety, wolfed down the cake but released no captives.

Boot, a lapsed conservative, is disgusted by the current horde of Maga Republicans. Even so, he admits that Trump’s most blustery slogan originated with Reagan, who led his own crusade to “make America great again”. A pair of Trump’s eventual fixers lurked on the fringes of Reagan’s first presidential campaign: Roy Cohn and Roger Stone arranged for an endorsement that enabled Reagan to win the usually left-leaning state of New York. But the candidate himself always denied knowledge of such deals, and when Boot catches Reagan twisting the facts – for instance by reminiscing about his military valour during a war that he actually spent in Hollywood – he treats him as a self-deceived fabulist, not a liar.

For Trump, making America great means aggrandising and enriching himself. Reagan, to his credit, had no such mad, greedy conceit, and in 1994, in a handwritten note informing his “fellow Americans” that he had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, he touchingly excluded himself from the “bright new dawn” that he predicted for the country. Later, unsure of who he was or what he had been, he wondered at the reaction of passersby when he was taken for supervised walks near his home in Pacific Palisades in Los Angeles. “How do they know me?” he asked his minders. The erstwhile celebrity had declined into nonentity; Mr Norm was at last truly anonymous, at least to himself.

after newsletter promotion