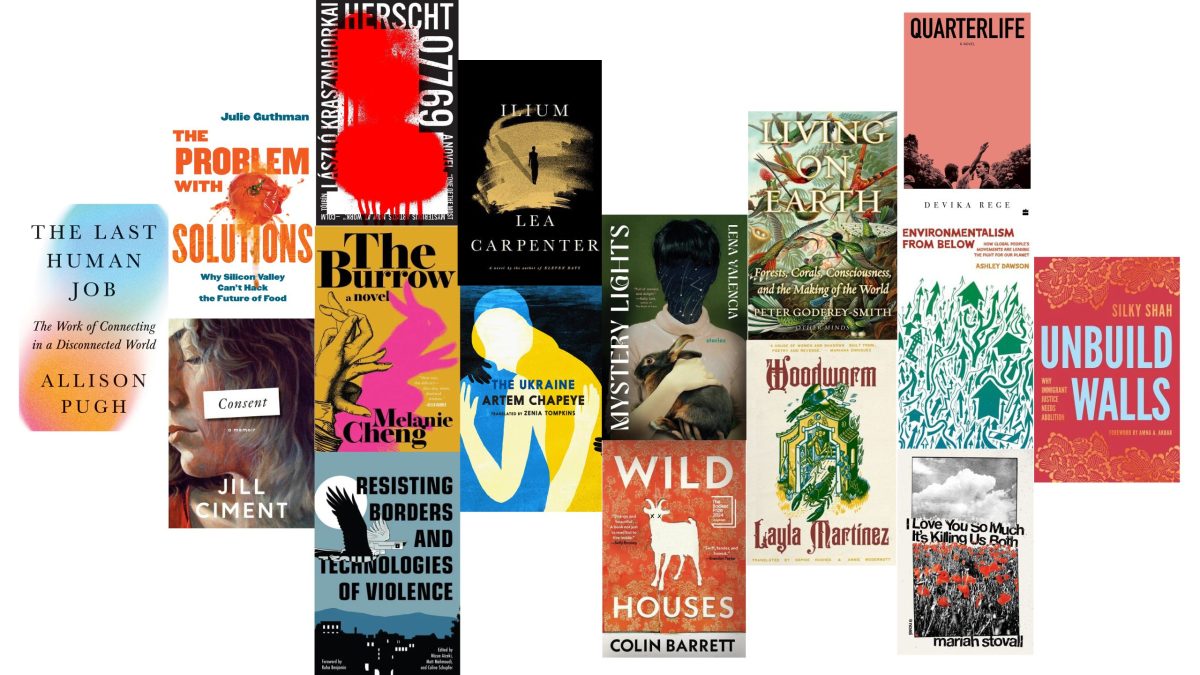

What were the books of 2024 that dazzled, challenged, and inspired us? For this, the 12th-annual edition of Public Picks, section editors for Literary Fiction, Borderlands, Literature in Translation, and Technology; series editors for Public Thinker and B-Sides; and our managing editor and one of our editors in chief tell us about their favorites. Take a look back on 2024 with one of these Public Books Public Picks!

B. R. Cohen

Public Thinker Series

The Problem with Solutions: Why Silicon Valley Can’t Hack the Future of Food by Julie Guthman (University of California Press). I had been waiting for this book, one confronting the false premises and blinkered technocratic incursion on food and agriculture by the hacker class. Guthman is the one to write it. She has long been the leading voice at the intersection of science and technology studies and food studies, consistently articulating the ways political and cultural conditions shape fields and food markets alike. The gist of The Problem with Solutions is well tipped by its subtitle, with Guthman giving us a book that tackles an especially insidious version of twenty-first century technosolutionism. The problem isn’t with technology, it is with a culture of venture capital backed predatory digital capitalism—forgive my clunky modifiers—that I had hoped would somehow be taken down by the HBO satire Silicon Valley a decade ago (a reference Guthman makes too). Unfortunately, to my naïve sensibility, satire doesn’t defeat its subjects fully enough. But the clarity and insights of Guthman’s writing will help. This is the most thoughtful and forceful account of problematic collisions between food and technology I’ve read not just this year, but in a very long time.

Megan cummins

managing editor

I Love You So Much It’s Killing Us Both by Mariah Stovall (Soft Skull). I was amazed by this debut novel. First person at its best, I Love You So Much It’s Killing Us Both tells the story of Khaki Oliver and her intense friendship—and its even more intense unraveling—with Fiona Davies. Stovall darts back and forth between 2007 and 2022, from high school to college to adulthood, giving us what feels like not just every one of Khaki’s thoughts, but every twitching impulse, every hidden urge. This book is filled to the brim; it would be dizzying if it weren’t so compelling. Fiona, and her eating disorder, is a constant in the book (her presence and absence both somehow ghostly); and so is the punk rock scene, where Khaki is often the only Black girl at every show she attends. The book is a delight (if an intense one) even for those of us who aren’t cool enough to get all the references. Not to worry, though—there’s recommended listening at the end. Oh, and did I mention the jaw-droppingly good lines? I returned my library copy and bought my own because the temptation to underline was too great.

Wild Houses by Colin Barrett (Grove). I’m a devotee of Colin Barrett’s short fiction, and his first novel is every bit as beautifully styled as his two collections, Young Skins and Homesickness. Set in Ballina, County Mayo, Wild Houses is kickstarted by the kidnapping of teenage Doll English, whose brother, Cillian, owes a hefty sum to people who are tired of waiting. Dev—a loner on the periphery of those to whom money is owed—finds himself forced to keep Doll at his home; and Nicky, Doll’s girlfriend, becomes entangled in a chaotic scheme to bring him back. Beneath the swift and gripping plot, the book shimmers with reflection. “Believe it or not, I know what I’m like,” Cillian says to Nicky at one point. “Every so often, it dawns on me, in cold horror.” And Dev, stunned in the aftermath of his participation in events, reflects, “That was what made it all so difficult. You couldn’t do anything until you did another thing first.” And that’s true in so many ways in Wild Houses: You might be able to see to a point in the future—as Doll’s kidnappers see a way to getting their money back, as Nicky can see a future beyond her life in Ballina—but before you get there, there’s all the other things that must be done first.

Mystery Lights by Lena Valencia (Tin House). There’s horror at the edges of daily existence—and the ten stories in Lena Valencia’s gorgeous debut, Mystery Lights, bring it front and center. Is the threat in the dorm the ghost of a 19th-century fur trapper, or the boy down the hall? Is it a bigger terror to see ghosts, or to lose your ability to see them? And when a mindfulness retreat drives you to the brink, is violence the only way to get your sanity back? Valencia breaks down the typical boundaries we hold ourselves within to show—beautifully, menacingly—that the supernatural might be closer than we think (and we might all be more unhinged than we believe). I was riveted from start to finish, and I welcomed a whole host of new characters into the world of my literary favorites.

Nicholas Dames

Editor in Chief

Quarterlife by Devika Rege (Liveright). A remarkable debut novel that feels as if it had been lived with and thought through for years, its every choice deeply considered and yet also brave, risky—it’s got an assurance rare for first books. It’s a group portrait of Indian 20-somethings right before, and then in the aftermath of, the 2014 election that inaugurated the Modi era; as such it’s a historical novel of the very recent past, delicately attuned to the possibilities that 2014 negated and the compromises it necessitated. It’s therefore a novel of tipping points, decisions from which there is no turning back, leavetakings. Most of all, though, it’s alive with argumentation, fervent debate and roiling self-doubt, enacting the splendors and miseries of democracy in a deeply antidemocratic moment.

The Ukraine by Artem Chapeye, trans. Zenia Tompkins (Seven Stories). Pungent and (sometimes bleakly, sometimes spikily) comic character studies of a country that was on the eve of total war, the war that is the fruition and negation of all its innumerable complications and ambiguities. “I’m describing the moment at the bifurcation point,” Chapeye writes in his introduction— “when no one knows in which direction change will take us.” There’s novelistic irony and wit, sociological precision, and historical weight to each little world here, and all of it serves to produce something like a national “imagined community” that is totally disabused of any romance but also absolutely urgent. The title story, which brought Chapeye international attention when it was published in the New Yorker in 2022, is only a small sample of the book’s spirit: a disillusioned, tenacious humanism.

Herscht 07769 by László Krasznahorkai, trans. Ottilie Mulzet (New Directions). Quantum theory, neo-Nazis, migrants, petroleum, forlorn hopes that centrist politicians will save the day: Krasznahorkai’s latest is a step less mythic, a step more mimetically contemporary, than the novels like Satantango, The Melancholy of Resistance, or Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming that made him a totemic (and even, in his forbidding way and to some of us, beloved) figure. Which isn’t to say that it’s all that different. The novel’s central figure fits within Krasznahorkai’s gallery of obscurely damaged, eerily gentle innocents, and his signature apocalyptic atmosphere remains, if a bit more in the vein of a thriller than his usual ominous thrum of dread. In other words, an ever so slightly more “realist” Krasznahorkai. Or is it just that our world has gradually become more like Krasznahorkai’s imagination? (And also: a one-sentence novel, more proof that we’re living in the great era of one-sentence novels.)

tara K. menon

Literary fiction

Ilium by Lea Carpenter (Knopf). “Then the new style began.” The epigraph to Lea Carpenter’s Ilium is from John Le Carre’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. Carpenter’s debts to the king of spies are clear, but her gripping third novel demonstrates her own mastery of the modern espionage thriller. Early in the novel, the unnamed British female narrator falls in love with a much older American man. She doesn’t know it at first, but he means to recruit her. She’s a perfect asset—lonely, vulnerable, an orphan—and, more importantly, the final, necessary piece in a years-long joint CIA-Mossad operation. (The novel is loosely based on the real life killing of CIA station chief William Buckley and the decades-long campaign to avenge his death.) After her husband-handler dies, the grieving newlywed is sent, in the guise of an art dealer, to the French house of a Russian oligarch. The action moves slowly, then all at once. Ilium is mesmerizing—at once a riveting thriller and a brilliant character study–and with it, Carpenter claims her place alongside Le Carre and Graham Greene.

Consent by Jill Ciment (Pantheon). When she was seventeen, Jill Ciment had an affair with Arnold Mesches, her 47 year old art teacher, who was married with two teenage children. Soon after their relationship began, Arnold left his wife and married Jill. The couple stayed together until Arnold’s death in 2016, at 93. In her first memoir, Half a Life, published in 1996, Ciment cast herself as a relentless seductress. In Consent, her second attempt at narrating their life, she asks: But was I really? It would be too simple to say that Ciment is rewriting the story of her life after #MeToo, but she does use the paradigm shift to pose some tough questions. In Consent, she doesn’t just revise basic factual details of their courtship (she didn’t kiss him first, he kissed her first; he didn’t take much convincing; he made his desire clear), she also ruthlessly dissects the way she first told the story. She reprints whole passages from Half a Life and exposes what she falsified, what she obscured, and what she left out completely. Then, she interrogates her motivations, as a wife, and as an artist: Why did I tell it that way? This is a radical experiment in revision, and it is deeply compelling.

The Burrow by Melanie Cheng (Tin House). Grieving family adopts pet bunny during the pandemic lockdown. Who wants to read that? Not me, I thought. But because of my implicit faith in the taste of the booksellers at Three Lives in the West Village, I picked up Melanie Cheng’s The Burrow anyway. The novel begins some years after Jin and Amy, a married couple living in Melbourne, lose their baby daughter Ruby in an accidental drowning. (Amy’s mother, Pauline, was bathing Ruby when she had a stroke.) Desperate to help their older daughter, Lucie, move forward, Jin decides to bring home a bunny. Soon after, Pauline is sent to live with the family after a short stint in the hospital. Every chapter, clearly marked by a name, is told from the perspective of Amy, Jin, Pauline or Lucie. In unsentimental prose, Cheng shows the four still living members of this small family, each still heavy with grief and guilt, trying to find a new way to live with each other. Another writer might have made the subject matter (baby dies on grandmother’s watch) maudlin, but Cheng refuses every temptation. Instead, she gives us a quiet, subtle novel about how grief refashions the delicate rhythms of marriage and parenthood.

a. naomi paik

BORDERLANDS

The following books all give us insights and tools for confronting the anticipated state violence we’ll be enduring.

Unbuild Walls by Silky Shah (Haymarket). In her book Unbuild Walls, Silky Shah reflects on her decades of work as a migrant justice organizer in Grassroots Leadership and Detention Watch Network. She focuses on the feedback loop between mass incarceration and migrant criminalization that has swept away both citizens and migrants into its vortex. US imprisonment regimes “made immigrants a target” and the system of jails and prisons enabled the deportation machine, while the criminalization of migrants has fed mass incarceration in turn, creating a migrant prison boom that only threatens to grow. Shah reflects on the evolution of organizing, as movements moved towards making increasingly radical demands. Rather than, for example, working to ameliorate the conditions of confinement or find alternatives to detention that would instead expand the carceral net, she and other organizers sought to address the root causes of migrant detention and deportation regimes and have continued to fight for the end of migrant detention altogether. Focusing on the years of sustained organizing as it unfolded and adapted to changing conditions, including changes wrought by their successful campaign, Shah calls on migrant justice organizers to adopt abolition as the most effective way to connect with other movements against state and capitalist violence and build power. This is the meaning of her title, Unbuild Walls—not only the walls of the carceral state as manifest in borders, prisons, and detention centers, but also the “walls between our movements for social change.” We have no choice but to hear this message as clearly as possible, given the coming attacks on people and planet.

Resisting Borders and Technologies of Violence, edited by Mizue Aizeki, Matt Mahmoudi, & Coline Schupfer (Haymarket). Resisting Borders and Technologies of Violence emerges out of decades of social justice organizing across North America and Europe against the everywhere border, whose expansion to all spaces of society is enabled by technologies enhancing surveillance and social control. As they show in their investigations of borders, policing, digital identification, and “smart cities,” technologies cast as “neutral” by their proponents instead “hard-code suspicion … and intolerance” of already existing systems of power and oppression, like racist patriarchy, labor exploitation, and nationalism. Tech companies and states are innovating their wares against targeted peoples and places like migrants and Palestinians, layering new and old tools of state violence and control—walls and surveillance towers, detention camps and ankle monitors, papers and biometrics, drones and bullets. Crucially, the book doesn’t just offer analyses of the dystopian world such technologies are creating. It also highlights campaigns and organizations who have already been fighting and winning against such pervasive and yet unknown technologies of control. Like Unbuild Walls, the book’s analysis cannot be so easily dismissed as pie-in-the-sky idealism but gives material, actually existing examples of organizing that move us closer to an abolitionist future.

Environmentalism from Below: How Global People’s Movements Are Leading the Fight for Our Planet by Ashley Dawson (Haymarket). Ashley Dawson’s Environmentalism from Below shows us how climate change and environmental destruction are “the mother of all crises” that brings together many “threads of injustice” rooted in imperial, racial capitalism. It offers an unflinching assessment of planetary destruction from agriculture to cities to energy to the extinction crisis to migration. He offers multiple examples of “fake fixes,” like carbon offsetting or “fortress” approaches to conservation, whose solutions to environmental devastation are destined to fail because they work within capitalist structures to defeat them. They constitute what Ruth Wilson Gilmore describes as efforts of trying to use capitalism to save capitalism from capitalism. But, again, Dawson does not leave us with a catalogue of catastrophe. His book shows us what “environmentalism from below” looks like right now, under current conditions, supported by real world examples of successful campaigns organized by movements in the global South among those most directly affected by but least responsible for global environmental degradation. The numerous examples of environmentalism from below confront the structures of racial, imperial capitalism at the root of climate change and environmental destruction, which also explains why they are so intensely targeted by state violence—from criminalization to outright assassination. And yet, as dire and existential as the climate and environmental crisis is, Dawson shows us the many ways people are fighting and winning struggles against capitalism for life itself.

Bonus books: My bonus books are those of R. F. Kuang. After being blown away by Babel (Harper Voyager) in 2023, I plowed through the Poppy War series (which traumatized me) and Yellowface and hope graduate school doesn’t get in the way of her writing more fiction.

john plotz

B-Sides

Living on Earth by Peter Godfrey-Smith (FSG). There is a Robert Frost poem about the oven-bird, which he finds touchingly un-musical.

The bird would cease and be as other birds

But that he knows in singing not to sing.

The question that he frames in all but words

Is what to make of a diminished thing.

While reading Peter Godfrey Smith’s brilliant account of the lyre-bird’s ability to copy virtually any sound—and then go on to copy another lyre-bird copying that sound—I couldn’t get Frost out of my head. In Godfrey-Smith’s telling lyre-birds copying one another may be “the oldest recording medium on earth,” so Frost’s “diminished thing” is also emblematic of the amazing omnipresence and unfathomable age of communication between (any and perhaps all) living beings: “Something is done by one organism to be perceived by another, and done with the aim conscious or not of affecting the other’s actions or responses in some way.” Godfrey Smith’s magnificent trilogy (I earlier raved about his 2017 Other Minds) has always aimed at broadening our understanding of how many species belong to the chattering classes. This book helped me to see what follows, ethically as well as practically, from communication’s omnipresence.

No micro-review could do justice to the range of this book, which moves on from communication to culture, understood as the non-habitual, non-inherited forms of action passed on among cohabitating groups of animals. While specifying that humans have raised cultural transmission to a new level, Living on Earth notes the forms of cultural transmission (including tool-use) that other species exhibit: life in water rather than on land makes that comparatively hard for dolphins, cephalopods and fish, but it’s remarkable just how well they sometimes manage.

Godfrey-Smith build a strong case for non-human individual experience—not just sentience, but perception, cognition, self-awareness (in some ways the argument resonates with David Pena Guzman’s compelling When Animals Dream ). That lends an unprecedented depth to the ethical turn at the book’s end—which includes a compelling case against factory farming because it can never provide to farmed animals “a life worth living.” The book ends by invoking Walt Whitman’s hope for life’s ongoingness: “Let not an atom be lost!” It persuaded me to think of that atomic re-cycling as delightfully open-ended; songs, thoughts, habits and actions can endure, not diminished but ramified as they cross barrier after barrier.

BÉCQUER SEGUÍN

literature in translation

Mona sloane

technology

The Last Human Job by Allison Pugh (Princeton University Press). Allegedly, we know so little about AI that the best way we can describe it is as a “black box”. Deeply fascinated, if not obsessed, with this technical obscurity, we often forget the territory that truly remains obscure: “the social” in the age of AI. Allison Pugh expertly and eloquently sheds light onto many corners of AI’s terra incognita. She guides the reader through many years of her deeply sociological research on the inner workings of human connection. Following people whose job it is to relate to another human, Pugh carefully develops the concept of “connective labor”: the work of seeing the other and making them feel seen. The stories she shares debunk AI’s obscurity, because they demonstrated how is put to work in the form of crude classification and prediction technologies that render genuine sociality and connective labor illegible to machines, and therefore less valuable in a world in which professions are increasingly standardized and metricized. It is hard to imagine a better book that can show us just how (anti)social AI can be, and how social we really are. ![]()