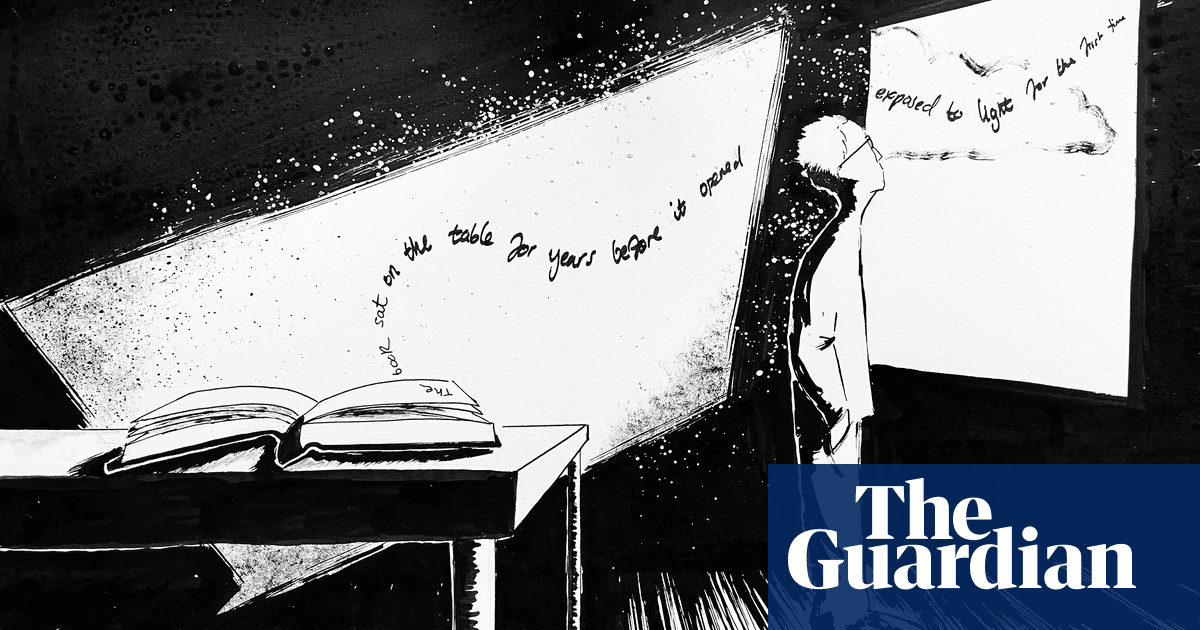

The Reader

The book sat on the table

for years

before it opened to a page

exposed to light

for the first time.

In their new surroundings

the words trembled

shaking all meaning

from their assembly,

the reader unable to enter.

Then the ink began to run

past the margins

to the mahogany to the floor,

random drops collecting themselves,

expanding from within.

The reader saw fit to stand

by the window,

following a cloud

till it stalled in front of the sun,

sweeping its passage along eyes closed.

As the sky proceeded

to draw the ink from the floor,

affixing the once-quivering words

to the slow-moving cloud,

the reader read the page in the dark.

And when the day’s shadows turned in

for the night

the book closed as it had opened

without a hand,

the reader calling it a day

of prayer.

The title of this week’s poem by Howard Altmann, declares its focus. This individual, always known as “the reader”, sustains an almost continuous presence, but it’s not until night falls in the penultimate stanza that they’re able to read the all-important page.

Uncontroversially, the poem opens with the physical existence of the book, one that has “sat on the table / for years”. The book’s location is a dark place, a room in the mind, perhaps: because of some unpredicted reaction to light or enlightenment it now seems to acquire independent agency. It wasn’t opened, like any ordinary book, but “it opened”. We are given the idea of the reader as non-participant, and this already opens the poem to questions about the different forms there are of the act of imaginative perception we call “reading”.

No instant enlightenment flares from the exposed page, and the words are destabilised. They “tremble” and lose their meaning. The reader is present, but incapacitated, shut out from the “assembly”. This is an interesting choice of noun: words are assembled in the act of making sense of them, but an “assembly” can also imply a community, brought together and bound by national, religious or political affiliation.

The ink runs, and carries the depleted words away, on to the table and on to the floor. There they re-group, “random drops collecting themselves, / expanding from within”.We as the poem’s readers are implicated because we, too, confront a mysterious narrative: we ask how to assemble the thoughts in the poem. And we may remember other, less interestingly puzzling pages – an exam question that, clouded by our panic, seemed not to make any sense whatsoever, or some formal communication, dense with official cliches, acronyms, instructions, deadlines and threats.

Clarification, as so often, occurs not through frantic concentration on the words, but a certain inattention. Once the reader’s focus has lifted away from text towards light, clouds, sun and shadows, the meaning of the text begins to be restored. As the book had once “sat” on the mahogany table, so the reader pointedly, authoritatively, stands by the window, “following a cloud”. The verb “following” suggests the movement of eyes and mind when reading, but when the cloud becomes “stalled in front of the sun”, it continues “sweeping its passage along eyes closed”: the act of imagination is sustained. The words’ earlier disintegration is reversed, and, in the deeper-clouding darkness, the protagonist finally reads the page.

The colloquialism “turned in / for the night” refers to “the day’s shadows” and suggests a blessedly peaceful, human ordinariness has been regained. The book closes itself, and the poem might have closed with “the reader calling it a day” – enough has been accomplished, it’s time for rest. Instead, Altmann takes the thought much further than we readers expected. His reader is “calling it a day // of prayer.” It’s not simply that the day has been made sacred by the accomplishment of the reading: the day was the reading.

What book, what kind of book, has the reader encountered? It might be a sacred text: that would fit the allusion to “prayer”. But I don’t think the book is sacred in the usual sense. Returning to the images of flowing ink, I see a handwritten book, a diary or memoir which is some last personal testament, perhaps not meant to be touched by any other “hand”. For the reader, it was the perception of a language of shattered “assembly” which made the reading so difficult and elusive.

The poem records an intense but ultimately secret encounter. It doesn’t tell the readers outside it what the all-important page has said. Yet our reading experience, similarly dependent on the flight of words into the imagination, might after all come near to mirroring that of “the reader” in the poem. The single poem might be our equivalent page in a bigger story.