Llyfr Geirfa fy Nhad / My Father’s Vocabulary Book

What was he reading

bron bob gyda’r nos — almost every night?

He was wrth fy modd —

at his pleasure — learning that rhawn

was horsehair. As for his soul

ar ddifancoll — lost in perdition? Swearing

was By Goblin — Myn Coblyn and prissy lout,

llabwst. My father’s Welsh

was Biblical, so when he was dying

and asked me, ‘Beth yw gwelltog?’

we felt the shadow of the valley of death.

Gwelltog is green, as in pastures, lie down.

The experience of emotional abuse can separate a person from their own mind. This is one of the insights in the memoir, Nightshade Mother: A Disentangling in which the Welsh poet, writer and translator, Gwyneth Lewis, explores her struggle to survive the domination of a furiously judgmental and possessive mother. Interviewed about the memoir, she said “poetry has been an invaluable tool in the process, because it’s not coercive, it rewards exploration and failure; the ability to change your mind is built into the form.”

Lewis allows her prose the leniency she values in the poetic. Nightshade Mother makes room for short poems, Lewis’s and others’, and quotes various texts: the author’s parents were fluent writers themselves, and diaries, letters, inventories, etc have usefully been preserved. Now and again, passages of invented dialogue dramatise Lewis’s inner debate, the painfully “doubled moral vision” of a split self. Above all, her narrative style allows for easy shifts in temporal and emotional perspective, and recognises conflicted emotions even as the psychological destruction progresses. The blameworthy, however culpable, are allowed their complexity.

It’s noteworthy – and moving – that the daughter took part in the care of both parents in their failing years. When writing in Nightshade Mother about her father, Gwilym, Lewis tells the troubling story of an initially loving parent who, as she fights for adolescent autonomy, retreats from his daughter and instead becomes his embattled wife’s defender and “accomplice”.

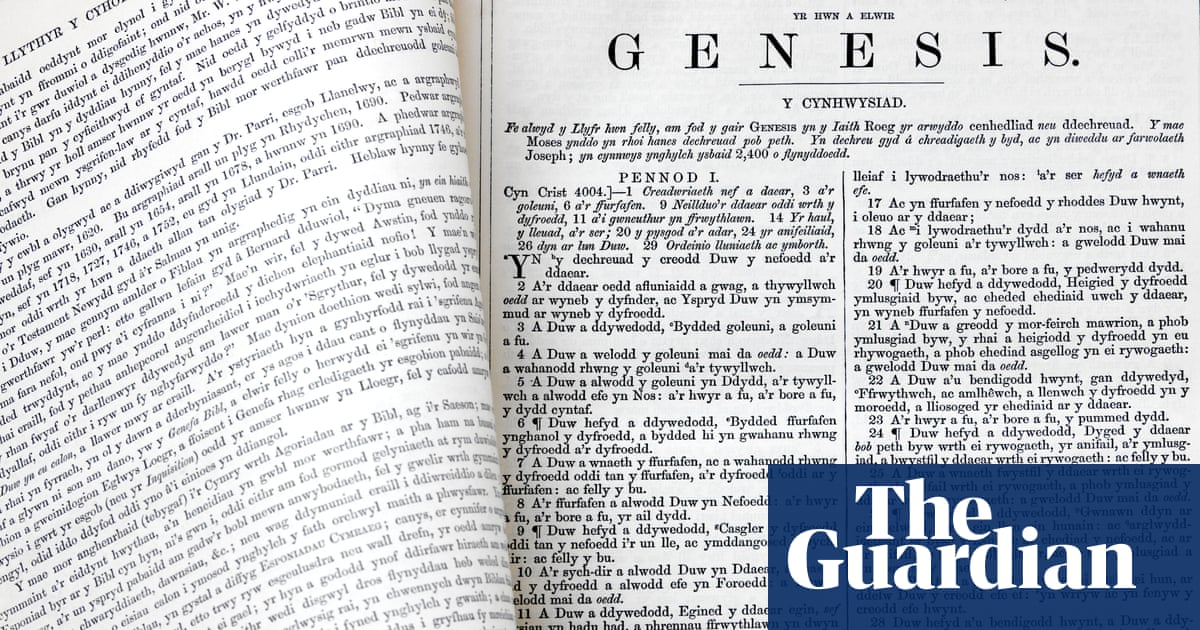

This week’s poem appears in the memoir’s second chapter, exploring Gwilym’s earlier life. It shapes itself around terms and phrases from the lists he made in his vocabulary book as he was working, with the meticulous organisation of a navy man, to perfect his Welsh. The macaronic language foregrounds his bilingualism. When first published in Lewis’s Welsh-language collection Treiglo, the poem’s English words must have seemed boldly assertive.

Lewis writes that she “wanted to embody how you can hear a person strengthening his Welsh deliberately, in a book which is a description of him dying out of language altogether. One of the most distressing aspects of watching my father die was his increasing use of English, when he’d taken such good care of his Welsh all his life.” The pained emotional restraint of My Father’s Vocabulary Book contrasts revealingly with the mood of another poem, Welsh Was the Mother Tongue, where Lewis is a young child learning English with her father.

For the anglophone reader, seeing the italicised Welsh phrases and words neighboured by the poet’s translation into English is reassuring. It allows us a little glimpse of the way difference is bridged and intimacy suggested by the translation being presented as though it’s a mirror of the original. A recording of the author reading this week’s poem helps us bring the sonic differences of the two languages into harmony.

Poem of the week

My Father’s Vocabulary Book

The “vocabulary” quoted in his daughter’s elegy, though only a small sample, shows Gwilym had a poet’s range of verbal pleasures. He’s interested in words that are rough-textured and practical (rhawn/horsehair) or literary and elevated (ar ddifancoll/lost in perdition). There’s the hint of mischief in the selection: the “swearing” seems innocuous, unless “By Goblin — Myn Coblyn” is stronger stuff in Cymraeg. It’s a mystery why the word “llabwst” meaning “lout” has gained an adjective, “prissy”, which implies over-refinement – almost the opposite of loutishness. Lewis says she simply copied down what was in the notebook. Perhaps the combination was Gwilym’s special invention for a person he knew, one who combined both qualities in a particularly infuriating manner. Or perhaps “prissy” is a euphemism for “pissy”.

The vocabulary book closes after four short stanzas. The poem concludes with a memory of the question spoken by Gwilym when he was near death: “Beth yw gwelltog?” (What is green?) The Welsh word “gwelltog” literally means “grassy”. So Psalm 23 is evoked and “the valley of the shadow of death” made manifest. (See Salm 23 here.)

The earlier line of the psalm (“He maketh me down to lie / in pastures green”) is quoted in the briefest manner, without emotional emphasis: there is no “dying fall” in the English monosyllables, “lie down”. For readers of the memoir, there’s an extra dimension, though, acquired from the beginning of the chapter where the poem appears. Gwilym’s father had been a coal-miner, and Lewis had discovered among his possessions “a tiny booklet of psalms, the paper’s grain impregnated with coaldust”. Gwilym’s memory of the 23rd psalm may have been formed early in his childhood; perhaps the black coaldust on the treasured book had entered his imagination for its contrast with the imagery of green pastures, and some childlike puzzlement lingered on to phrase the deathbed question. It’s the gnomic quality of that question that completes the portrait-in-vocabulary of the poet’s father, and gathers the fragments of his thought into that vast interior country, sensed throughout the memoir – the complex uniqueness of each human individual.