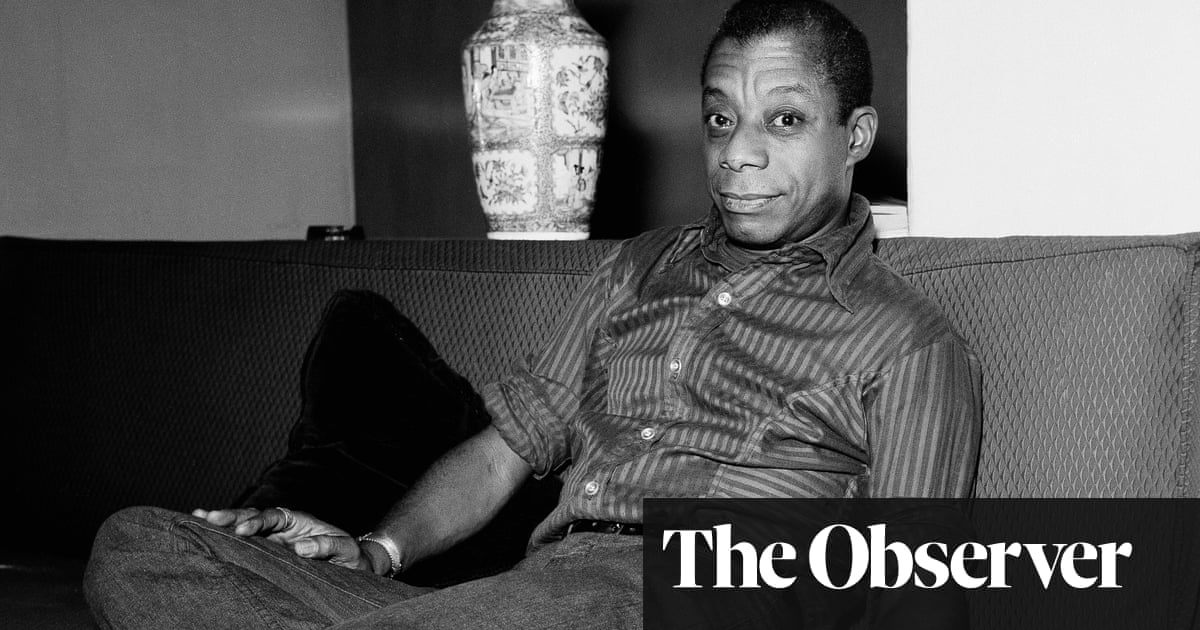

James Baldwin, gone these past 37 years, is back. In truth he never went away. In the centenary year of his birth (2 August 1924), with reissues of his short story collection Going to Meet the Man (1965), and the autobiographical work No Name in the Street (1972), along with staged readings of his famous essays, rereleases of myriad documentaries and literary festival panels interrogating his wide influence, from his scintillating oratory to being a queer black style icon, the man is born again. Imprinted on our consciousness are those big, wide-awake eyes on the lookout for trouble but hoping for love, the mischievous, gap-toothed grin of gossip and delight, the rich gravitas of his voice, as foreboding as thunder but often edged with humour and always humane – all signifiers of the distilled wisdom and passion of his writing.

From close to 7,000 pages of published work that emerged from his capacious mind, two convictions emerge most strongly: the danger of being “at the mercy of the reflexes the colour of one’s skin caused in other people”; and, second, that “to be a negro in [the US] and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage almost all of the time”.

These concerns might relate specifically to North America but such is the irresistible universality of Baldwin’s writing that these twinned sentiments resonate throughout the world. When people, especially black people, read and hear Baldwin, it is as if they are hearing themselves. On his death in 1987, Toni Morrison wrote: “I have been thinking your spoken and written thoughts for so long I believed they were mine.”

The same is true of many who have wrestled with their identity – whether of race or gender – buoyed up by Baldwin’s writing as an inoculation against shame, in works of fiction such as Giovanni’s Room (1956). His determination to write a gay novel without a single black character was also a brave rejection of his publisher’s preference – after his first book, the novel Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), where blackness was front and centre – that Baldwin should stay in his lane and build his brand as an erudite black polemicist.

Nonetheless, any audit of his life shows that, even when he wanted to escape his colour, the vexed question of blackness was the primary subject of his prose. In the outbreak of the latest culture wars, especially in the US, readers have increasingly looked to Baldwin for guidance in his many books, including No Name in the Street and Going to Meet the Man.

In the former, he journeys to the southern states of the US, concluding that his white compatriots have invented “the negro problem” in order “to safeguard their purity”. But what finally strikes him is “the unbelievable dimension of their sorrow” rather than their wickedness; in their denigration of black people they diminished themselves.

Baldwin understands the psyche of the white American who is “bound up in a terror he cannot articulate, a mystery he cannot read, a battle he cannot win – he has simply become the prisoner of the people he thought to cow, chain or murder into submission”. Baldwin unflinchingly explores this theme in the harrowing title story from Going to Meet the Man. Jesse, a white police officer in a southern town, believes himself to be a good person, “protecting white people from niggers”. He’s haunted by the plaintive spirituals echoing from the prisoners’ cells and the suspicion that “they had not been singing black folks into heaven, they had been singing white folks into hell”.

As Jesse unthinkingly carries out his brutal job, he recalls a childhood memory – a learning opportunity given to him by his father – of travelling to a picnic where a man, guilty of “being black”, was tied up like a hog, tortured, castrated and finally lynched. The level of violence depicted in these passages, necessarily so, is so extreme that it’s obvious that the writing will have come at great emotional cost to Baldwin. In scenes like these, his prose emits a long piercing scream as it takes off from the page like a fighter jet on a mission to drop a payload of explosive truths across enemy territory, flying fast and low, risking hostile and friendly fire.

In No Name in the Street, he reflects on the public role that seemed to have been chosen for him, writing: “I was, in some way, in those years, without entirely realising it, the Great Black Hope of the Great White Father.” Unsurprisingly, at the time, he drew flak from both defensive white Americans who thought him too militant and black activists who considered him not militant enough.

Early supporters such as Richard Wright, a literary father figure to Baldwin when he was trying to establish himself as a young writer, came to believe Baldwin was ungrateful when the rising star shunned Wright after having followed him to Paris. But James Campbell, in his estimable biography of Baldwin, Talking at the Gates (1991), argues that he was “magnificently generous” towards his own family and friends. However, Campbell also concedes that his subject had an extraordinary capacity to hold on to a grudge: “seldom hesitating over a breach of promise”.

Few would have blamed him, though, for harbouring resentment towards Eldridge Cleaver after his egregious portrayal of Baldwin in his memoir, Soul on Ice (1968). The Black Panther activist lambasts his mentor for his alleged sycophancy towards “his first love – the white man” and for his “racial death wish”, manifest in his homosexuality.

Answering the charges brought by Cleaver in No Name in the Street several years later, Baldwin skirts over the obvious homophobia and is magnanimous in his conclusion that “the artist” (Baldwin) and the “revolutionary” (Cleaver) are driven by a vision and “need each other, and have much to learn from each other”.

Baldwin’s essayistic reflections are often marked by the personal: he uses anecdotes from his own life to uncover more universal truths. One of the most tender and revelatory examples of this is found in No Name in the Street when he recounts buying a suit to attend Martin Luther King’s funeral after the civil rights leader’s assassination in 1968. Baldwin confesses, in an interview soon after the event, that the unbearable sadness subsequently associated with that suit meant he’d never be able to wear it again. Later, a friend who’d read the interview rang him asking to be bequeathed the suit. Baldwin acknowledges that his pal couldn’t afford his own privileged “elegant despair” and gave in to the request, recognising the loss to all African Americans of King’s murder: “The blood in which the fabric of that suit was stiffening was theirs.”

after newsletter promotion

Baldwin once said that it was his ambition to be “an honest man and a good writer”. He was clearly both. The insights of the former boy preacher, writer, civil rights activist and public intellectual are just as poignant and relevant as they were at the height of his powers in the 1960s and 70s. Admirers seek out his books almost as manuals or manifestos for living. His words, though, were never commands; only appeals to the morality of the reader. In the centenary year of Baldwin’s birth, the clarity, fire and empathetic humanity of his voice is needed now more than ever.

No Name in the Street by James Baldwin is published by Penguin Classics (£9.99). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

Going to Meet the Man by James Baldwin is published by Penguin Classics (£9.99). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

Further reading

Three new books celebrating his centenary year

On James Baldwin by Colm Tóibín (University of Chicago Press)

James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues” by Tom Jenks (Oxford University Press)

God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin, edited by Hilton Als (Dancing Foxes Press/Brooklyn Museum)