A little while ago, Adam S Leslie was in Blackwell’s in Oxford, where he works, when a customer came in, picked up a copy of Lost in the Garden, and started telling his friends how good it was. “Actually, I’m the author,” Leslie eventually admitted, to the customer’s delight. That’s when it sank in for the 50-year-old bookseller: the novel he had written in his bedroom was “actually a real book out there in the world”.

And now that real book has won a real literary prize: last week, Lost in the Garden was named winner of the Nero book award for fiction. “It’s a little bit of an out of body experience,” Leslie tells me. “I’m looking at all the stuff online and going, ‘This person with my name is having a great time!’”

Caffè Nero set up its awards for “unputdownable books” two years ago, filling the gap left by Costa Coffee, which abruptly ended its literary prizes in 2022. Last year’s winner of the fiction category (and of the overall Nero Gold prize) was Paul Murray’s The Bee Sting, a widely loved novel that many had thought would win the 2023 Booker prize. The judges have made a much more daring choice with Lost in the Garden, a folk horror novel about three women who travel through a fantastical version of rural England. It didn’t get much media attention when it was published by Liverpool-based independent press Dead Ink last May, so when it appeared on the Nero shortlist in December, it seemed like the underdog, up against positively reviewed novels by Donal Ryan, Jo Hamya and Suzannah Dunn.

But the judges – novelist Kevin Power, bookshop owner Will Smith and journalist Zoe West – were clearly won over by Leslie’s novel, praising it as “a hazy, hypnotic book that reflects contemporary Britain through a distorted lens” when they chose it as their winner last week.

“Hazy” and “dreamlike” are words that come up a lot in descriptions of the novel – and it turns out parts of it have actually been taken from Leslie’s dreams. The author, fascinated by his thoughts as he was drifting off to or out of sleep, began writing down these “nonsense phrases”, and they became the sections of the book that one character hears on a mysterious radio station.

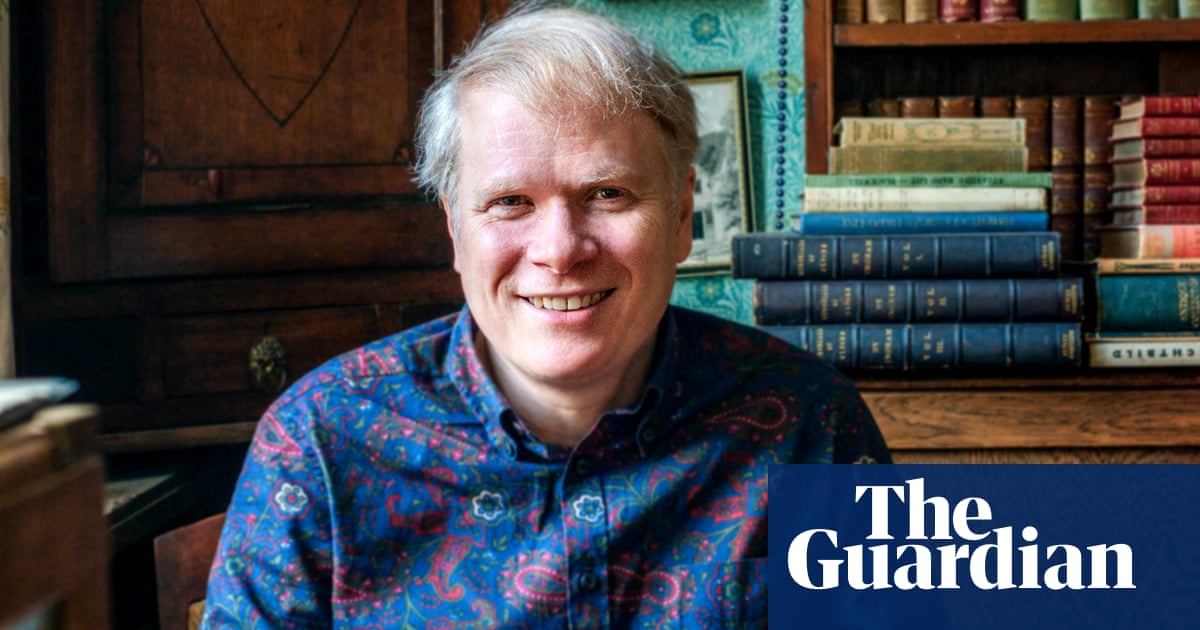

This kind of playful fascination is clearly a central facet of Leslie’s personality. He excitedly points out the historic artefacts in the side room of Blackwell’s bookshop where we are speaking – an office that once belonged to Basil Blackwell, son of the shop’s founder, and kept in its original state, with William Morris wallpaper and a Bakelite telephone. Against this stately backdrop, Leslie could be mistaken for one of the city’s many professors, white-haired and dressed in a paisley shirt and green jumper, exuberantly gesticulating as he speaks. It was Oxford’s reputation as a place for “literary” and “artsy” types to thrive that drew him here nearly 10 years ago – before that he had been living in Milton Keynes, where, he says, “everywhere I worked I was the weird one”.

Ever since completing a film diploma in Middlesbrough in the 90s – he had aspirations to become a director – Leslie has tried to “work the minimum amount of days a week I can get away with”. He always turned down promotions and chose low-commitment, minimum-wage jobs, he says, “so I’d have enough time for writing”.

Though he has been writing fiction since he was 13, it wasn’t until just over a decade ago that the author first had his work published, bringing out two novels with a publisher that has since gone under. He also has a handful of screenwriting credits to his name, but before Lost in the Garden he had been struggling to get his writing career off the ground. Yet he carried on, spurred by a quiet confidence “that one day I’d be a writer”.

It was in his teens that he first came up with the idea for Lost in the Garden. He originally thought of it as a film script, because it was a book about film that got him thinking about the story: Fantastic Cinema by Peter Nicholls.

“I got really fascinated by films like Céline and Julie Go Boating and Stalker,” he says. But in the days before DVDs and streaming services it was difficult to get hold of these films, so he just imagined what they might be like from Nicholls’ descriptions. While he did “absolutely love” Céline and Julie Go Boating when he eventually saw it, it was “nothing like the film I had in my imagination”. For 30 years, the story of that imagined film was “always in the back of my mind”, he says. When he was furloughed from Blackwell’s during the Covid-19 pandemic, he decided to “just write it and see where it goes”, and Lost in the Garden began to take form. He can see now that elements of the novel were subconsciously influenced by the fear of that time: at the beginning of Lost in the Garden we learn that dangerous ghosts have started roaming the English countryside and villagers are encouraged to stay indoors.

Leslie’s childhood was one of the novel’s more conscious inspirations: its rural setting is based on the Lincolnshire village Carlton Scroop, where the author grew up. His parents – a stay-at-home mother who had formerly worked for magazine publisher DC Thomson and a father who did “computery stuff” – moved the family from Nottingham to Lincolnshire when Leslie was a baby, and he had “one of those classic 80s childhoods where your parents would let you go off for the day”.

Like Lost in the Garden’s characters Heather and Rachel – who are adults but have retained a childlike quality – the novelist’s childhood friends often got up to high jinks in the countryside. But while Leslie’s friends “were very good at trespassing”, he was “far too anxious for it” himself. The author thinks his own personality is “about 30% Heather” as, like the character, he has “a little bit of a Peter Pan complex”, but “70% Antonia”, the novel’s shy, nervous character.

Leslie references his anxiety several times during our conversation: he says it’s why he’s not cut out for film directing or performing his music live (he writes psychedelic pop-rock songs under the name Berlin Horse). So I’m surprised to find that he has no problem being in front of a camera: he worked as an extra in the 00s, and even had a line – “It must have been the doctor!” – in a 2008 episode of The Bill.

after newsletter promotion

It’s because as an extra he was fulfilling somebody else’s vision, not his own, he explains. “When everything’s resting on me making decisions in that moment, that’s quite full-on.”

I ask Leslie about the author biography in the back of Lost in the Garden, which says that though the author “isn’t married and has no children”, he “did once have a box of snails”. Even the snails, which he began collecting on walks (“I only picked up ones that weren’t going to survive”), proved too much of a commitment after a while.

“I kept them for as long as they lived but didn’t renew them for beyond that.” The writer likes to keep his responsibilities to a minimum, he explains. “I‘ve never had much interest in just normal boring everyday life,” he says. “I’m generally fairly consumed by creativity and pop culture. I don’t know if I necessarily have a real life outside of that.”

He says “it’s so tempting to daydream” about winning the Nero Gold award, for which he is up against Colin Barrett, Sophie Elmhirst and Liz Hyder, who won the prize’s other categories. The four winners each receive £5,000, but the overall winner will get £30,000, which would be enough for Leslie to quit his Blackwell’s job and write full-time “at least for a year or two”. He’s planning a political thriller next, and has a few screenplays in the works.

As we leave the bookshop together, Leslie shyly points out the display of his books that his colleagues at Blackwell’s have put in the window – as if he can’t quite believe that his childhood hobby has turned into this. His lifelong commitment to writing is clearly at the heart of everything he does: “I think, well, I’d better not let that 13-year-old chap down.”