“I wasn’t even pissed,” Hanif Kureishi says, as if somehow that would have made it better. The writer is talking about the accident that left him a tetraplegic. Or, as he likes to call himself with classic Kureishian brutality, a vegetable. Though he’s not. His body may be broken, but his brain isn’t.

It was Boxing Day 2022 and he was in Italy. Back then the writer spent half his idyllic life in Rome, half in London. His three sons were adult and independent, he had enough money to enjoy a good life, he was in love with his wife, Isabella d’Amico, and, at the age of 68, the enfant terrible of English literature was content in a way he’d never been. He was having a beer, watching the football on his iPad, when he had a dizzy spell. He stood up, took a few steps forwards and fainted. He later discovered he had fallen on his head and broken his neck. Kureishi was left paralysed.

Would it have made any difference if he had been pissed? “I could have reproached myself more. You seek some kind of explanation; some kind of finality. Why has it happened to me?” At the London Spinal Cord Injury Centre, where he was transferred after spending a year in Italian and English hospitals, he was surrounded by people asking themselves the same question. Virtually all had suffered horrific fluke injuries resulting in broken necks. “Some twat had fallen out of bed and broken his neck. Some other twat had fallen down the stairs and broken his neck.” Twat, in Kureishi’s lexicon, is not an insult – just a synonym for person. “A nice guy tripped over a rake in his garden and broke his neck. So everybody in there is thinking, what the fuck? One guy, a close friend of mine, a political philosopher and rock climber, fell on his head and was paralysed from the neck down.” Kureishi’s neck break is partial. He still has feeling and movement in his limbs, though he cannot walk or grip with his hands.

Kureishi thought his life was over. For starters, he thought he might die. Then, if he did survive, what was the point? He could no longer do anything for himself. The man who had lived a life of belligerent, cussed independence, doing what the hell he wanted when the hell he wanted, was now wholly dependent on others for everything. Almost two years on, he has written a book about the accident and life afterwards. With apt and typical directness, it’s called Shattered. And Kureishi has been in every way.

As a writer, he is known for a different kind of shattering – of taboos. He made his name as the screenwriter of Stephen Frears’s 1985 romcom My Beautiful Laundrette, though romcom suggests a tweeness at odds with the reality. It featured a gay love affair (a rarity 40 years ago) between a young Anglo-Pakistani man and a white skinhead with a history of racist violence (Daniel Day-Lewis in his breakthrough role). The film was a groundbreaking mix of romance, racism and identity politics. Kureishi was nominated for a best original screenplay Oscar.

His next film, Sammy and Rosie Get Laid, portrayed a British man of Pakistani ancestry and a white woman in an open marriage, against the backdrop of London lit up by riots. Kureishi’s first and best known novel, The Buddha of Suburbia, is a thinly disguised fictionalisation of his own upbringing that caused huge upset in his family. His 1998 novella Intimacy told the story of a young man leaving his wife and two young sons, with coruscating candour – Kureishi had just left his wife and two sons. There wasn’t a scab from his private life not worth picking over in his fiction.

Kureishi’s subjects were belonging (and not belonging) and transgression. He was calculatedly transgressive. His screenplay for My Son the Fanatic tackled Muslim fundamentalism in 1997, while The Mother is a film about a woman in her mid-60s (played by Anne Reid) initiating an affair with a man in his early 30s (Daniel Craig). Nothing was unsayable or undoable in Kureishi’s work. And it still isn’t.

Shattered is exuberantly scatological, soaked in the catheterised piss and enema-extracted shit of his new life. It is also a tribute to those who have helped him through the worst of it; a prolonged screech of injustice; an exploration of dependency in which he portrays himself as half baby, half tyrant; and a defiant fist pump for survival.

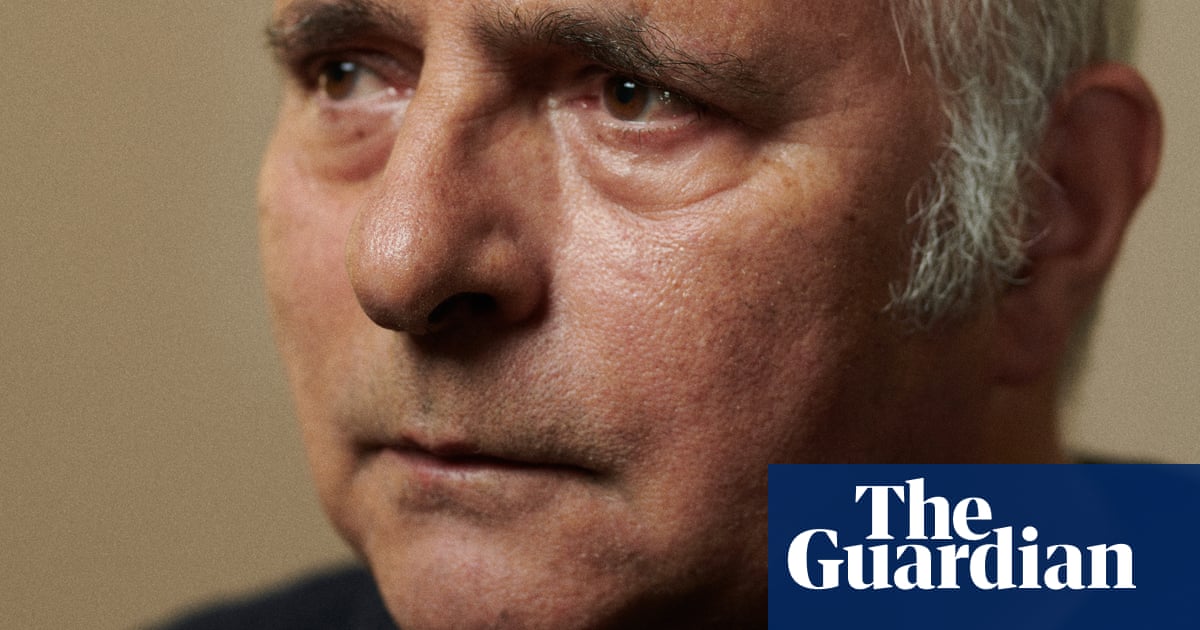

We meet at the home he shares with d’Amico, an Italian literary publicist, in west London. His 24-hour-a-day care worker Camilla opens the door. Kureishi is waiting for me in the living room. His electric wheelchair is state of the art, with tyres fit for a 4×4. There are any number of prints framed on the walls – a John Lennon photo here, a Rembrandt self-portrait there, an Ingres nude, family pics, a miniature Alex Ferguson in a tiny glass cup on the mantelpiece (he is an avid Manchester United fan). In the corner is the hospital bed he sleeps on.

Kureishi is wearing a sloppy purple jumper and baggy tracksuit bottoms. He used to pride himself on his style, but tells me it’s pointless wearing a smart pair of trousers when you can’t walk. He is warm and curious, wanting to know about life at the Guardian, what else I get up to, which football team I support. He asks if I’d mind sitting on the sofa so he can position his wheelchair to look at me when we chat. Camilla brings him a black coffee with a straw, and a beaker of water.

The house is large, on three storeys, but Kureishi tells me he’s not seen the second and third floors since the accident. He is confined to the living room and kitchen, and it frustrates the hell out of him. Having said that, he’s much more positive than he has been, largely because he’s back working. “Most people with spinal injuries never work again. If you’re a ski instructor or a lorry driver, you’re fucked. I met a lot of people in hospital with spinal injuries. They go home, but what they do at home is just watch the TV – they can’t work. Their lives are over.” He’s lucky to be a writer, he says – though he has had to learn a new way of writing that requires huge patience, both for him and those helping.

It was only a couple of days after the accident that he started writing again. He was desperate to find out if he could still do it. So he dictated his thoughts to d’Amico. “She would sit on the end of the bed taking dictation. It was madness. I was shouting at her, yelling, half-dead.” Why was he yelling? “Urgency. I had this very strong desire to say something. To see if I could go back to being a writer. I was bombed out of my head on all kinds of shit, but I wanted to find out whether I was still the same person. We did a blog every day. Then the kids came over to Rome and my son Carlo brought his computer, and we started publishing them on Substack.”

He talks me through the process. “I’d lie in bed and write the blog in my head, and would see the order of the thoughts. I’d try to memorise the sentences so when Isabella or my boys came [Kureishi has 30-year-old twins Carlo and Sachin with film producer Tracey Scoffield, and Kier, 26, with psychologist Monique Proudlove], I could just dictate it straight to them. I had to learn how to write in this completely new way.”

What surprised him, and gave him such hope, was that when they published the blogs on Substack, people wanted to read them. Hundreds, then thousands, then tens of thousands. He realised this was a subject that people wanted to hear about. What’s more, they wanted to hear about it from him. Carlo effectively became his editor. “He’d tell me I’d missed stuff out, repeated myself. He’d say, ‘That’s really boring.’”

I tell him how much I like the book. “Oh good, thank you, mate! All that pain and misery. I don’t know how you enjoy it, but people say they like it.” Perhaps enjoy is not quite the right word. It’s fascinating, painful and very funny against the odds.

The coffee has had time to cool. “Simon, could you give me a hit of that coffee, would you mind? Sorry to ask you, mate.” I put the cup to his lips and he sucks from the straw. In the book, he says how angry Sachin gets with him because of his lack of pleases and thank yous. Today, his manners are impeccable.

Kureishi says it was only when he came out of hospital that he realised how different he is now from most people. In hospital, pretty much everybody used a wheelchair. “When I finally got out on to the street and went up to Shepherd’s Bush [in west London], everyone was walking about, and you think, what the fuck, how can they walk? There are so many of them and there’s one wheelchair on the street. You have to get used to all that, and I have got used to it now.”

He’s also getting used to the cost of life as a tetraplegic. “I have physio every day, which I pay for myself and is costing me a fucking fortune – nearly £100 a day, so money really matters. If I take a taxi into London to have supper and come back here, the taxi will cost me £200. Who the fuck has got that kind of money?”

But he knows that among the unlucky, he’s one of the luckiest. “One guy rang me up and said, ‘I want to give you £25,000.’” What did you say to him? “‘Fuck me! For fuck’s sake.’ And he said, ‘No, I’m going to give it you. I know you’ve got terrible expenses, etc’ and he gave me the money.” Was he a close friend? “He was a friend, but not a close one. It was so moving and upsetting in a way.” Why upsetting? “That somebody would be so generous to me and see what a pickle I was in and what I needed.” Was it hard to accept? “I felt embarrassed. You don’t want to ask people for money. I didn’t ask him for money. I would never ask for money. So I felt embarrassed, yeah. Suddenly you become a supplicant.”

There are the friends who come round, bring food, feed him, brush his teeth, give him a head massage and read him a bedtime story. They spend hours with him. He’s humbled by their generosity and it’s made him question what kind of person he was before the accident. “It’s so beautiful that somebody’s doing this for me. Then you think, would I do this for someone else, and I think it wouldn’t occur to me. Most of the people who do all that for me are women, and you think, I wish I could do this for them now. But it’s too late for me to do this now, and I regret I didn’t do it before.” In Shattered, he writes, “I wish I had been kinder. If I get another chance I will be.” But he knows he won’t get the chance to help people in the way they have helped him.

The selfishness of his former life is a recurring theme in Shattered. He’s not apologising for his past, just acknowledging it. He calls himself an “opportunist social climber” and says he loved hanging out with the older generation of British literary heavyweights – Salman Rushdie, Martin Amis, Julian Barnes. The mid-80s through to the 90s was a wonderful time for writers – advances were huge and plentiful. He might have been politically on the left, but he didn’t half benefit from the Thatcherite ethos. “In the 1980s, selfishness was the character ideal of the age, and fucking hell was it fun.” He makes no bones about being numero uno in his life.

There was always a laddishness to Kureishi’s writing; a desire to prod and shock. In Shattered, he writes about his proneness to choking since the accident. “I am more intimate with the Heimlich manoeuvre than cunnilingus.” To even think of comparing the two takes a degree of perversity. He boasts about taking cocaine with his sons. After fantasising about “the world of filth and depravity”, he is reminded “how close sexuality and disgust have to be for sex to retain its edge”.

Shattered is sex obsessed. But this time it’s not sex as a possibility or inevitability, it’s sex as an impossibility. The accident has left him impotent. I tell him he reminds me of Michael Gambon’s Philip Marlow in The Singing Detective, hospitalised, in psoriatic agony, but instead of trying to think of unsexy things to stifle an erection, here he’s conjuring up sexual fantasies to see if he’s capable of getting one. “Well, that’s a very perceptive thing to say. I was lying in bed like Michael Gambon in that show with these beautiful Italian nurses washing you and cleaning you, and you can’t feel anything. Your sexuality has gone for ever. They’re leaning over you, and they smell beautiful, and they’ve got great eyebrows, and all your dreams have come true. You’ve got three nurses tending to you, and there’s nothing you can do about it.” Kureishi is incorrigible. You sense he really does believe that if only he’d been in full working order, the nurses would have jumped into his hospital bed to enable him to fulfil their fantasies.

In Shattered, to see if he can get himself going, he recalls a threesome he had in his promiscuous 40s after he had left his first wife. A younger woman he hooked up with in Amsterdam gets in touch to tell him she’s in Britain. He asks her to visit him. Would you like me to bring anything, she asks. Yes, he says – chocolate, weed, magic mushrooms and a friend.

What strikes me about the passage, I tell Kureishi, is the way you depict yourself as a taker rather than a giver. He smiles. “Well, that night I was obviously looking for an adventure, but I wouldn’t say that was an everyday experience. I wrote about it because I thought it was funny.” It’s also bathetic. “It was a disappointment,” he admits. “I’d been expecting a threesome with two women and she turned up with her boyfriend who was the same age as me, clinically depressed and barely said anything. He just sat on the end of the bed with his head in his hands watching me fuck his girlfriend.”

He launches into a spluttering phlegmy cough. It sounds so uncomfortable for him. “Excuse me,” he says when he gets his breath back. “Coughing is really important to clear your lungs, and I’ve got reduced capacity. It’s difficult for me to clear my lungs.”

Kureishi tells me about Nietzsche’s theory of the eternal recurrence – the philosophical concept that our lives will repeat infinitely and in each life every detail will be exactly the same. He says he lay in his hospital bed, revisiting the past, asking himself whether he’d want to change it. “You can’t live a life without thinking how stupid you were and what a mistake that was, and how self-sabotaging that was. I’ve been in therapy for a long time, and my therapist kept me from some of my more self-destructive impulses to do with substances and bad relationships and stupid behaviour. And having kids has also kept me on the straight and narrow.” When he totted up his balance sheet, he concluded the one thing he wouldn’t change at all is his time with d’Amico. “She’s my destiny; the person I want to be with.”

Did he ever think something awful could happen to disturb that contentment? “Yes. When I turned the TV off and went into the kitchen to close the windows at night, I used to look out and think, how much longer is this going to go on? There’ll be a day when this happiness will end. I always thought that way.”

Shattered is as savage as anything he’s written, but it’s also in large part a love letter to all those who have supported him – friends; strangers on the street; his sons; d’Amico; Scoffield, who emerges as heroic. “When I go out on the street, people come up to me all the time and say, ‘Well done, mate, I love your writing.’ Nobody approached me before. Now it’s every day. I’ve become a local celebrity because of the blog.”

In a way he wasn’t before? “It’s the disability. It’s pity. And it’s love. And it’s their generosity. You realise how kind people are. How loving they are.” He seems so astonished by the world’s kindness, I wonder if it’s because he himself used to have an unkind view of the world. Perhaps fans didn’t approach him because he seemed unapproachable – too cool for school. He doesn’t have time to answer before he is hit by another phlegmy coughing fit. “Excuse me,” he says. Time for a drink.

Over the morning, we’ve developed a curious, and rather lovely, intimacy. As I stand over him, putting the straw to his lips, he tells me how much he misses being able to scratch his arse. I almost offer to do it for him.

But there has been progress. Now he can scratch his face and eyes with his knuckles. It’s amazing how often you need to scratch yourself, he says, and when you have use of your hands you never think about it. “If you tied your hands up for a day and had to spend the day without their use, you’d see what they mean to you.”

He takes another sip of water. “Cheers, Simon. It’s great to have a Guardian journalist doing this for me at last!”

after newsletter promotion

The book also seems like a love letter to his father, Shannoo, who emigrated from Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1947 and met Kureishi’s English mother Audrey in a London pub. Shannoo spent his working life as a civil servant at the Pakistani embassy in London, but really wanted to be a writer. He wrote many unpublished novels. The depiction of him in The Buddha of Suburbia devastated Kureishi’s sister Yasmin, who wrote a letter to the Guardian saying he had sold his family “down the line” and she would not stand by and let it be “fabricated for the entertainment of the public or for Hanif’s profit”. She objected to his portrait of the family as working class and their father as a bitter old man.

Did she have a point? “My dad was posh. Really posh. My mum was working class. He came from a very wealthy and privileged family. An educated family. He wasn’t like a traditional immigrant who comes from a village and goes to work in Bradford. He came over to study law and he had 11 siblings and most of them were sent either to the US or the UK to study law or medicine.” Where did the family get the money from? “My grandfather was a doctor and a colonel in the British army and a big gambler. He was the highest promoted Indian in the army. They had servants and he had a big house.” As for his father, he can’t speak highly enough about him today. “He was a very friendly, charming guy. He was a beautiful man, a very sweet man.”

Why is Kureishi so often described as being of Pakistani heritage rather than Indian? Simple, he says. He was brought up to think of himself as Pakistani. “My dad went to work in the Pakistan embassy. You can’t work in the Pakistan embassy and call yourself an Indian! So he called himself a Pakistani, even though he’d never been there.”

The Buddha of Suburbia was adapted for the stage by Kureishi and director Emma Rice earlier this year. He admits he felt uneasy when he watched the play. “I thought, for fuck’s sake, what have I done? That’s my mum, my dad, that’s our house, our street. I’ve put them on the stage and made them look like idiots. I’ve embarrassed myself and I’ve embarrassed them.”

It feels like an apology of sorts. But suddenly he changes tone. “Then I thought, it’s a warm, moving story about race and growing up in England, about pop music, sex, leaving home. It’s not a simple story of Hanif’s put his dad on the stage and made him look like a fool.”

So was Yasmin right to say it was unfair on the family? “I would say that’s my story; that’s my version of it, and you have your version of it and somebody else will have their version of it. In any family there would be a collision of utterances.” And now he goes full Kureishi. The regret of a couple of minutes ago has morphed into an audacious celebration of his generosity. “Growing up in Bromley [in south-east London] in the 70s was boring. Really fucking boring. It was always raining and cold. And you see the play and it’s really funny and lively. I’ve done them a fucking favour. I’ve really brightened it up. There’s a lot of music in it, people are in bands, having sex and being creative.”

There is another potential “What have I done?” moment in Shattered. While it’s loving towards his father, it’s anything but to his mother. He describes her as “the most boring person I ever met”, adding that “liking other people was one thing she couldn’t bear”. Was it necessary to write that? “Well, me and my mum always had a beef,” he says. Is she still alive? “No, she died about four years ago. Tracey warned me about that. She said, ‘Don’t say that shit about your mum.’ But I believe it. She said, ‘I liked your mum, she was charming, she was funny, she was sweet.’ Well, I had various beefs with my mum over the years.” Such as? “She was depressed most of her life. She was very withdrawn.” He calls out to his care worker. “The coffee’s getting a bit cold, Camilla, d’you mind making some more, please?”

It’s cruel to call her the most boring person you’ve met, I say. “She wouldn’t engage with you,” he protests. “Depressed people can’t. They don’t. It’s not really her fault.” I tell him I’m a depressive and I can engage perfectly well with people. He looks amazed. “How long have you been depressed?” Most of my life, I say. “You don’t seem depressed to me. You’ve got a good sense of humour. You’re up for a laugh.”

Would he have said she was the most boring person in the world if she’d still been alive? “Yep.” How would she have reacted? “I think she would have been offended.”

What does he think Yasmin will make of the book? “We’ve got a bit of a beef going on,” he says. What about? “God knows. She came to see me in hospital and there was a minor beef. I can’t even remember what it was about.” Has there always been beef? “Yeah.” Who’s normally responsible? “Well, as you can imagine she would say, ‘Oh, he wasn’t very friendly.’ And I’ll say she wasn’t very friendly.” He thinks at some point Sachin will give Yasmin a ring and tell her she and Kureishi should bury their pride and sort out their differences.

I’m still thinking about his mother. What does he think it says about him that he felt he had to write about her in this way? “That writers have a splinter of ice in their heart, as Graham Greene says. When I’m teaching writing, a student tells me a juicy story and I say, ‘That’s great, write it down’ and they’ll say, ‘I can’t say that – if my mum read it, she’d hate me for it.’ And then you think, well, you’re not a fucking writer, are you?”

Are the boys similar in character to him? “They’re very sweet. They’re really good boys, and they’re better children to me than I was to my parents.”

He loves being a writer, he says – possibly more than ever. It might take his carers two and a half hours to get him ready for the day – breakfast, washing, turning him over, cleaning his catheter, administering suppositories, hoisting him up, dressing him – but when it’s 10am and he’s sitting in his wheelchair, ready to write, or ready to be helped to write, he feels alive again. “Finally when I’m up, I can become a writer. I can become a human being. I can talk to you, talk to people. And it’s a relief to come back out into the world.” He never thought he would. Kureishi says at times he believed it was pointless going on. But he was so dependent on others that he couldn’t even kill himself without their help.

D’Amico, who has been working upstairs, walks in. Kureishi looks at her adoringly and apologetically. “We are just talking about how I ruined your life,” he says.

She laughs. “Ah, how you ruined my life much before the accident? Ten years ago!”

I quote a bit from Shattered where he writes, “Isabella is broken by the accident.” Is that how she sees it? “It’s a difficult question. I’m not precisely happy about the accident, but we are much more organised, we know more things, we are dealing with it pretty well on the whole. We still have a nice time. It’s an adjustment.”

The worst time, both agree, is night. “Sometimes I wake up in the night,” d’Amico says. “In the night Hanif’s really pessimistic.” Kureishi’s eyes start to moisten as she talks. “Isabella sleeps upstairs and I have to sleep in the hospital bed. It’s horrible, I don’t want her to sleep alone, but you can’t get two people in that bed.”

One positive, she says, is he’s more gregarious. “After his accident, Hanif is much more keen on seeing friends. He liked to see friends before, but we were also lazy. I used to travel a lot. He has become more social.”

“I hate being alone,” he says. “It’s depressing.”

D’Amico heads off upstairs to get on with her work.

Were you crying when she was talking, I ask. “Yeah. Well, I don’t want to hear that she’s been hurt by this shit. And I don’t want to feel I’ve inflicted on her a life that she doesn’t want. That’s terrible, that you’ve done this thing to all these people around you. That they have to be devoted to you in a way they didn’t anticipate. You put a terrible strain on other people. So I’ve got to write and keep being productive myself.”

Kureishi says writing the book has helped restore his confidence. And, he hopes, this is just the start. As well as the adaptation of The Buddha of Suburbia, he’s working on the follow-up to Shattered and a screenplay for a movie. What’s it about, I ask. He smiles. “It’s going to be about a bloke staying in Rome who falls on his head and breaks his neck, then wakes up in hospital and has to learn to live again.”

He says he’s slowly adjusting to being a disabled person. Are there any pluses? Well, he’s learned more about the realities of life; perhaps he was too cocooned before. “Trauma can create opportunity. So you say to yourself, this terrible thing happened to me, but how am I going to adjust to it and what can I do to speak from it, as it were. So I’ve got a new energy for writing, despite the fact that my body is broken. I’m not going to give up.”

The bit of movement that has returned to his hand has given him hope. “I’ve started having occupational therapy and am trying to learn how to write with a pen. I’m like a four-year-old. I can make gestures and movements.” His goal is to be able to write his name, one day. “Eventually I’ll be able to sign one of my own books again. That would be a big deal for me.”

D’Amico bursts into the room with a sense of urgency. “I’ve been thinking about it. I’ve not been broken. I’ve definitely not been broken,” she says passionately. “I was never broken.”

“Yeah,” Kureishi says quietly. “‘I never noticed he’s a vegetable.’”

D’Amico raises her eyes. She’s heard it all before. “As I say to Hanif, fortunately he’s a talking vegetable.”

Does he talk more than he used to? “No, no,” she says.

“Never fucking shuts up,” Kureishi says with a defiant grin.