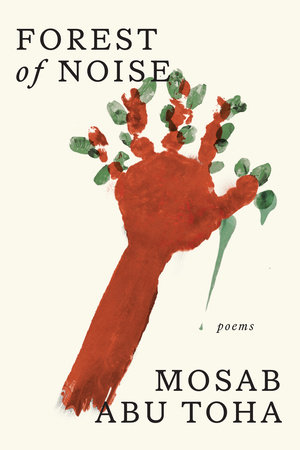

Mosab Abu Toha’s second poetry collection, Forest of Noise, is a heart-wrenching account of life in Gaza, under the tightening grip of the Israeli Occupation. Abu Toha morphs his stories in verse, into a range of forms. Some written as letters from Gaza, detailing the minutiae of everyday life under siege, “Children feel petrified at night… Grandfather has not left his room for seventeen days.” Some are instructions on what to do during an Israeli airstrike, “get a child’s kindergarten backpack and stuff/tiny toys and whatever amount of money there is…/and some soil from/the balcony flowerpot…” In others, Abu Toha pulls his reader closer in his grief and loss as he speaks of dreams he has for his homeland, dreams of his grandfather, his younger brother buried at sixteen, at the cemetery now “razed by Israeli bulldozers and tanks.”

Mosab Abu Toha is a Palestinian poet, scholar, and founder of the Edward Said Library, Gaza’s first English-language library, now decimated by Israeli attacks. His debut book of poetry, Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear won the 2022 Palestine Book Award and an American Book Award.

A few weeks ago, at Busboys and Poets in DC, I had the privilege of listening to Mosab Abu Toha read from his new poetry collection for the first time. The room turned still with the anguish he poured out, but particularly haunting were the stories he shared, the ones that didn’t make it into the collection because they are of his loved ones, his students, who died only a week or month before. It was a reminder that Palestine continues to be obliterated, that Palestinians continue to need us to amplify their voices.

Before you read the following conversation—on the confluence of identity and land, memory as inheritance, and America’s complicity in the ongoing Palestinian genocide—I want to leave you with Mosab’s words from the event, “Gaza is an open air prison—[it] is a mild statement. It is not a prison. I wish it was a prison. Who bombs a prison? Who starves the people inside the prison?”

Bareerah Ghani: I want to begin with the opening where you equate Gaza’s land and people to yourself. You say, “Every house is my heart…every hole in the earth is my wound.” Can you share your thoughts on the confluence of identity and land—to what extent are they inextricable?

Mosab Abu Toha: I, as an individual, could be anyone who has been killed, has been wounded. I’m a father. I could be in the place of parents who lost their children and their whole family. I could be the father who was killed with his own children, his parents and his extended family. I could be any one of these people. For us Palestinians, we love our land, our trees, everything around us. We have been in Gaza all our lives because of the Occupation. We are besieged by Israel not only from the land, but also from the sky, where the only kind of airplanes are the F16s and the drones bombing us from time to time. We are besieged from the sea—no one in Gaza can sail as far as 7 nautical miles, because there are Israeli gunboats and warships. So the land of Gaza is everything that I have. The trees in Gaza are the only trees I know. The holes in the ground are my wounds, because when the land is wounded, I am wounded. As a person who has known this land, this earth, this soil all my life, everything around me affects me. It harms me. Anyone who is harmed, whether it be a dog, a cat, a tree, a house, a wall, a plastic bag, it hurts me because this is the only thing that I have known in Gaza.

BG: In “Obit”, you mention you’ve left behind your shadow, and that it’s awaiting your return—“My shadow that no one’s attending to, bleeding black blood through its memory now, and forever.” I thought it was powerful, this insinuation that people of Gaza, no matter where they are, how distant, will continue to inhabit the land. I am wondering if you can talk about that poem, what you were trying to capture there?

MAT: I wrote this poem three years ago when I traveled to the United States for the second time. The first time I traveled, my wife and kids were with me, but the second time, I came by myself to finish my MFA Program at Syracuse University. So everything that I loved, cared about, that I can’t live without, was in Gaza away from me. And this shadow was the part of me that remained. My memories, my students, my family. Everything that couldn’t escape, that remained in Gaza, where I belonged and where I still belong, even though now I’m in the States, thousands of miles away.

I lost thirty members of my extended family in one airstrike… This shadow, which is the part of me that remained in Gaza, has bled seas of black blood.

Now, a year after the beginning of the genocide, this shadow has been terribly harmed by the Israeli bombardment from the sky, the Israeli land invasion, the shelling from the sea, the bullets from snipers, and from the armed quadcopters. I personally lost thirty members of my extended family in one airstrike in October last year, and I lost 3 first cousins, two of them with their husbands and children. Their whole families were killed. And I lost my last grandfather to illness because there was no medicine, no ambulances, no health care system for the past year. This shadow, which is the part of me that remained in Gaza, is still bleeding. It has never stopped bleeding, but in the past year alone, it has bled seas of black blood.

BG: I’m really sorry about your family.

MAT: The problem is not only with the Occupation, it lies with the governments. And the criminals supporting this Occupation. It’s terrible when I see that my country has been ravaged and destroyed by the Occupation, but it hurts more when I see people justifying whatever Israel has been doing, not in the past year, but for the past seven decades. And not only are they justifying, they are doing everything in their power to make sure that Israel continues to kill, to take more land. I keep saying this—it’s really evil of the governments of the world, especially of the United States, to keep saying that Israel has the right to defend itself, and to keep sending more and more weapons that kill children. And I’d like to emphasize that this is not a war on people in Gaza. It’s a war on families. They are not killing individuals. They are not killing, you know, a paramedic or a journalist. No, they are killing the journalist, his wife and his kids. They are killing the doctor, his wife and kids, and sometimes his grandparents, his parents, his cousins and siblings, who live in the same house. So when we hear the spokesperson of the White House, the President of the United States or the Vice President, being concerned, saying that we’re telling our Israeli partners to decrease civilian casualties, they don’t do anything practical to make sure that this loss does not continue. Instead, they make sure that Israel defends itself. And what does it mean, defend themselves? Kill more and more people in Gaza and the West Bank.

50% of the people in Gaza are under 18 and half of the other half are women. So about 70% of Gazans are noncombatants. And the remainder are people like me, teachers, nurses, drivers, people who don’t have anything to do with whatever happened on October 7, but they have been dispossessed, and are suffering because of Israel’s siege and its Occupation, because of Israel’s depriving us of having a normal life. And this is not last year, this has been going on for decades.

BG: In mainstream media, the Palestinian narrative has been framed as a conflict when really, it’s an ethnic cleansing, and America is particularly complicit in this erasure of your people. How do you battle this duality of, at once, finding refuge in a country but also being displaced because of it?

The poem, for me, functioned as a report. But it’s not about numbers, or the name of the place or the name of the person killed. It’s about what it means to lose someone.

MAT: I came to the States, not as a refugee, but to work at Syracuse University. I think it’s very important to speak truth to power, face to face. It’s true that I am in a country that is fueling the genocide, but this country is not 100% with the genocide. There’s been a lot of solidarity from the American people. We have a lot of students taking to the street, protesting the genocide happening in Gaza. We have a lot of people rooting for the Palestinians to get their freedom. It’s not about the ceasefire. It’s about the rights of the Palestinians to live in their own country, to have their own rights. That’s why I’m in the States. This is an opportunity for me to be here, to meet with as many people as possible, to travel to as many cities as possible, meet with the public, with my readers, especially now, as my second poetry collection is coming out.

BG: In this new collection, I couldn’t help but notice several poems are written in the form of letters as though the sender is wishing to preserve these everyday moments. And in many other places you emphasize the value of photos, especially of grandparents. What are your thoughts on memory serving as inheritance, as a source of preservation?

MAT: I haven’t seen my grandfather, Hasan. He passed away even before my father got married. The photo I had of him and the stories I heard about him—from my father, my aunts, and sometimes from people that I ran into—were the only things that I could inherit from him. I couldn’t inherit, let’s say, his jacket, his walking cane, or his passports, or his family’s photo album. These were all that kept me close to him.

So there are the memories that you hear about other people, in this case, my grandfather, and also my grandmother—I only remember seeing my grandmother once. She passed away in 2000, when I was about 8 years old. But there is also a memory that I could’ve had with my grandparents if they were still alive, and if we could be in Yaffa where they used to live before the Catastrophe of 1948. There are memories I could have made if Gaza hadn’t been under occupation and under siege for decades, memories I could have made with my wife and kids traveling, and to see our families in the West bank, or in Jordan, or with other people visiting us from outside. But it’s very difficult to leave Gaza, to go to the West Bank, to Yaffa and other occupied Palestinian cities, even for a visit. I tried multiple times to go to Jerusalem for a few hours to attend my visa interview and the Israelis denied me permission to appear at the American embassy. They are not only preventing us from returning to cities where our grandparents were expelled from, but are also preventing us from visiting an Embassy for a few hours. There are memories I could have made if these circumstances did not exist, and continue to exist in Gaza.

The memories that I did have—as a child, memories of my parents, my children—I wrote about them in this book. Preserving these memories is important because if the stories I know, if the things I had with me did not make it out with me, and if I did not share them with other people, like you and others who have never been to Gaza, it would seem like it never happened. If we did not know about what happened to the Jewish people at the hands of the Nazis, if there were no pictures, no videos, of course no one would believe that it happened. But because it’s documented and taught at schools here in the States, people will know, and they will sympathize, etc. But you know, what’s happening to the Palestinians is not something in the past. It’s happening live. It’s not memories we are narrating. Oh, you know, last year I lost thirty members of my extended family. I’m not telling you this a few years after it happened. I’m telling you the same day—I posted about it. And I posted pictures of some of my family members. I do this every day. Every one of us has been doing this every day. So it’s not something that the world is learning about, a few years later. We have been documenting this for a year and the world is reluctant to even call it by its name—a genocide.

BG: Absolutely. It’s horrifying. I can’t imagine what it’s like for you and other Palestinians who have family there, who live there, who have lost so many people. For those of us witnessing this genocide, we want to know what we can do. What would you say to people like me and others who are allies, who want to help. What can we do?

It’s terrible seeing my country being destroyed by the Occupation, but it hurts more when I see people justifying whatever Israel has been doing, not in the past year, but for the past seven decades.

MAT: Listen and learn from the people who are surviving. Don’t fall into the propaganda that’s been out for decades about what’s happening in Gaza. Learn about the people who did not make it, from the people who did make it. Never stop talking about Palestine, about what’s happening now, but also the reason why we are suffering, being massacred, for decades. The reason why all this happened.

BG: Thank you for sharing this. You’ve been really active on social media. You post daily about the situation in Palestine. How do you feel about social media, and its ability to reveal the truth about what’s happening to Palestinians?

MAT: Since the beginning of October 7, Israel has blocked the entry of food and medicine. And when they let a few trucks in, and people try to get to these trucks, they kill them. Israel has been controlling the number of food trucks, the amount of fuel entering into Gaza, but also the presence of international journalists and doctors. They have cut electricity, water, they have even cut the Internet connection. People are struggling to connect to the Internet through the use of some E-sim cards. So when people do connect to social media, they are trying to do what war journalists would be doing.

While I was in Gaza. I was a father, a son, a neighbor, a poet, and also, a reporter. I was posting pictures, translating some breaking news. I was doing the work of so many people, because if I was not doing it, no one would. And there are so many people who are doing this on social media which shows that we have so many stories to tell. And if we don’t share with the outside world, it’s lost. That’s why, we’re seeing a lot of Instagram journalists, photographers and video journalists. Many are normal people. Maybe they were farmers, people who were just taking pictures of the sunset, or a few children playing on the beach. They became journalists covering the war and running after each airstrike. And this tells anyone that there is no international coverage of the war in Gaza. That’s why people in Gaza are doing it. And then, the number of the journalists, whether they are video journalists or photojournalists or reporters, tells you the magnitude of the destruction that’s taking place in Gaza.

BG: Absolutely. As I understand, in your new poetry collection, there are some poems that you wrote while you were in Gaza, living through the current genocide. I’m curious about your relationship with writing and language, particularly English, which, if I am correct, is your second language?

MAT: It’s a foreign language. It’s not even a second language because in Gaza I never used it. I just use it to write, to communicate, but I’ve never used it even as a second language with people who are visiting, I’ve never used it outside of my room when I was in Gaza.

BG: And yet it is the language you write in. You tell these stories that are very integral for other people to hear.

MAT: Yeah, I think the poem was the best tool for me to share my experiences and also my feelings as I lived and survived the first two months of the genocide. Half of the poems in this collection were written during that time. Why, the poem? Because it preserves the experience and the feelings that come with it. Because you can write a poem and post it, and people will see it and feel it. I was posting many of these poems online because I couldn’t wait until it’s published in a poetry magazine, or the New Yorker. These poems cannot wait, just as people who get injured or burned because of airstrikes cannot wait until the border opens for them to travel and get treatment, so doctors do what they can using the scarce equipment they have.

As a poet, I write and, in a few minutes, I post the poem, and it goes out into the world, and people read it and feel it. The poem, for me, functioned as a report. But it’s not about numbers, or the name of the place or the name of the person killed. It’s about what it means to lose someone.

BG: Is there a particular reason why you write in English and not in Arabic?

My hope is to live in a country which is Palestine, where there is no occupation, no siege, where we can travel whenever we want, wherever we want.

MAT: Well, the people who are responsible for this ongoing genocide are in the West, not in the Arab world. Why would I write in Arabic and tell people how I feel? If I write in Arabic, to whom am I writing? Am I writing to my father and brother and my neighbor? They know. They have more terrible stories than me. When I’m writing in English, it’s not a choice of language. It’s a choice of audiences.

I write in both languages, by the way. But I don’t sit here and say, Okay, I’m going to write in English and English has certain constraints that are not found in Arabic. English is a language of communication, and poetry is a way of communicating. The people responsible for this genocide, be it in America or in Europe, speak English and they need to hear the stories in English, not in Arabic.

BG: In several of your poems you talk about survivors’ guilt and this idea that Palestinians who are surviving, must tell their stories. But in the undercurrent of that telling, there’s this necessity to prove that your life is valuable because Palestinians have been dehumanized so much by the West. How do you grapple with those things and the weight of it?

MAT: When I write poetry, I’m not trying to humanize Palestinians. I’m an artist. This is how I perceive things. I see details. When I write about the people I love, or the people I see and care about, my students, my neighbors, my house, the garden in our house, the sunset, the clouds, the birds, I don’t see the frame of the picture. I see the picture itself. I’m not trying to humanize Palestinians, so that people in the outside world would say, Oh, you know these people are really kind, oh they deserve to be alive. No, this is another function of the poem. I, as an artist, care about the details of everyone’s life. Not because I’m Palestinian, and I want to humanize my people. But this is the way life is. When there is an airstrike, I don’t see the victim. I don’t see the baby who was beheaded by the Israel airstrike.

I see the pacifier, I see the cot, I see the blanket. It’s visible there as much as the baby is visible. These details indicate that there used to be a life before death happened. I see the full picture. I don’t only see what happened after the airstrike. I also see what was happening before that, which is equally important.

BG: That’s powerful. I would like to ask—what is your hope for Gaza, for life beyond today?

MAT: Gaza is part of Palestine. So when I hope something for Gaza, I hope something for Palestine. My hope is to live in a country which is Palestine, where there is no occupation, no siege, where we have our own airport and can travel whenever we want, wherever we want. Where we can welcome anyone who wants to visit us, because in the past at least 17 years, no one has been able to visit Gaza unless they have an Israeli permit which is given mostly to journalists or human rights organizations.

This is in one of my poems—I want to see Gaza from the sky, from an airplane window, the way I see cities in the States or in Europe. When the airplane lands, I want to see what the streets look like from afar. I want to see Gaza from the sea, to see the water, and also the buildings and the refugee camp. I want to see all that from afar. I mean, these are just simple, simple dreams.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.