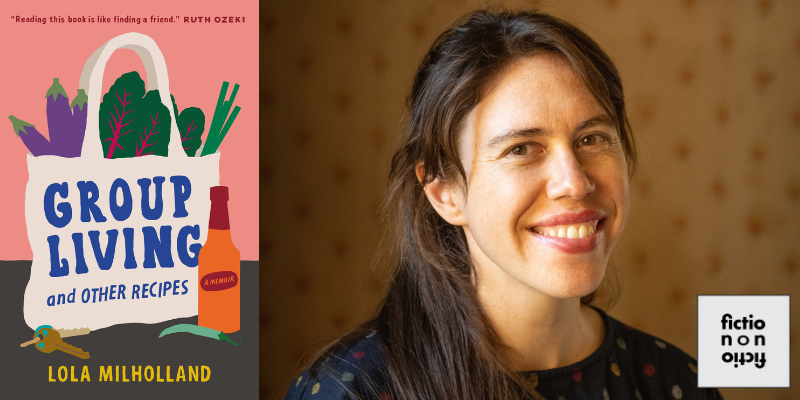

As the housing crisis worsens and Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris makes lowering housing prices a key part of her agenda, nonfiction writer Lola Milholland joins co-hosts V.V. Ganeshananthan and Whitney Terrell to discuss her experience with communal living. With traditional single-family homes economically out of reach for many Americans, Milholland talks about the social and financial benefits of living with others, including shared cooking and meals. She cautions that living with roommates will not solve the housing crisis and talks about the need for widespread and systemic change. She reads from her book, Group Living and Other Recipes.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

Whitney Terrell: Your book Group Living and Other Recipes is about the interrelation of housing and food. We’re gonna get to the food part, but let’s start with housing, or maybe a single house, which you call the Holman House in the book. At one point you write, “I didn’t live in the Holman House, but with it.” Can you introduce us to that house and talk about what you mean by living with it?

Lola Milholland: Yeah, absolutely. When I was five years old, my mom bought the house in Northeast Portland. It’s an old craftsman, and it was built around 1905 or 1906, and so it had had so many people living in it before we ever entered, and you could feel the history in the home itself. Right away, my parents found old chicken cages under the front porch from a time when people did subsistence living and have kept chickens there.

There are all kinds of secrets that you would just stumble upon as you went through the house, the things people had left behind and hidden in different corners. I had this strong feeling that, like the house had had its own life, and we were just one chapter in it. My parents loved to throw parties, and later, when I was an adult in the house, I had this feeling that the house wanted us to be throwing parties, like it needed a certain amount of human life pulsing through it just to be its fullest self. Sometimes I felt like we didn’t even want to have a party, but the house had sort of called it out of us.

WT: Could you describe it? Was it a two-story house? Three-story house? Did it have a porch? When you say craftsman, what does that exactly mean?

LM: Yes, I was talking to a reader, and they’re like, “it sounds palatial.” No, it’s a two-story house. It has a front porch. It’s painted white. It’s mostly wood. The beams and the structure of the house is old growth, so it has the materials of the landscape built into the home. The front porch just covers the front porch. You go in the door and you’re in the living room. And because of when it was built, it had very tall ceilings. When I was little, some people had dropped the ceiling to make it feel like a bungalow, which I think maybe was cooler at the time, so it felt much more cramped. My parents knocked that out at some point, and so it has sort of tall-ish ceilings. The ground floor has no bedrooms, but we’ve repurposed one room into a bedroom. The upstairs has three bedrooms.

So it was a house that big families, big multi-generational families, were living in at the turn of the century. Now we’ve built a back porch and a side porch. So we have a house that, as I always say, because there’s so many entrances just on the first floor, makes itself porous.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: It sounds really lovely. A significant part of the book focuses on the ways that the residents of this gorgeous house and other communal spaces are cooking for each other and labor sharing. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about the role that cooking and food play in communal living?

LM: Absolutely, I think food is often at the heart of many communities, and it certainly is in our house. We decided early on that we would have dinner together every night. So that means if one person cooks, they cook for everybody. If they want help with the cost of groceries, they just ask people to pitch in. So we do work on a sliding scale, but it means that people aren’t cooking their individual meals and then each only cleaning the thing that they think of as their own mess. When it’s a meal time, we are all together, and we sit down together, and you eat dinner with whoever is there that night. It’s not really rigid, this person cooks on Monday, this person cooks on Tuesday. It’s a lot more communicative, and if no one can cook, no one’s around, that’s fine, too. But I love the fact that when we are together in the house, and it’s meal time, we spend it together. We find out how our days were, we joke around, we process the news. You know, we have these small interactions that give you a sense of texture of another person, that can build a lot of intimacy.

WT: So I have a 14-year-old son, not super communicative right now. He’s very Clint Eastwood-y. I’m wondering if it would be good for him to be having dinner with a lot of people. Or, how did that affect your social engagement when you were younger? Or did you not like having people around? He hates it when I’m around, I can’t imagine me having extra people around.

LM: I think there’s a lot of ways to think about that. One is, you know, when I was his age, I remember rejecting my parents’ food. I remember saying, “Oh, I don’t need to eat that, I bought myself a super bag of Doritos, so I’m not hungry, you guys eat without me.” There is some time in your teen years where you’re figuring out who you are in opposition to your parents. I’m not a social scientist, but that just seems pretty apparent from every lived experience I’ve ever seen.

Something I think about in a communal house is, we’re only four, five, six people, but you know, if somebody’s feeling really social, and I’m not, I can just back away and let them interact with somebody else. The pressure isn’t all on the two people who are there to fulfill each other’s social needs. You know? If your son maybe doesn’t want to talk to you about something, but there’s someone else there, maybe he would want to. Or maybe, right now he’s in a time where he’s very internal, and in the future, he’ll want that. We go through different phases of our lives where we have different needs, and I think about that a lot with communal living. I don’t think everyone should live communally. That seems preposterous to me. We’re all too different, and we have too many different needs at different times in our lives, but there are times when it might really serve us, and those could be different for different people.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Vianna O’Hara. Photograph of Lola Milholland by Shawn Linehan.

*

Group Living and Other Recipes • Umi Organic • Living With Roommates Is Sorely Underrated |TIME • Can a $9 Lunch Cure Loneliness? | Oprah Daily

Others:

Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 7, Episode 33: “Brandy Jensen on the Mainstreaming of Polyamory” • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 7, Episode 29: “Jen Silverman on Generational Divides in American Politics” • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 7, Episode 52: “Myriam J.A. Chancy on Haitian American Communities” • Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard • Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard: “Home Prices Far Outpace Incomes” • The Gift: How the Creative Spirit Transforms the World by Lewis Hyde