Few writers can be considered as poignantly relevant decades after their passing as James Baldwin. The Harlem-born writer was often considered ahead of his time, a figure who managed to cut through the noise on issues of race, identity, and social justice and provide a framework to question politics and power. This year, on August 2, Baldwin would have celebrated his 100th birthday. He died in December 1987 in his Saint-Paul-de-Vence home in the south of France at 63, leaving a legacy of art, activism, and love that pours through his work.

Article continues after advertisement

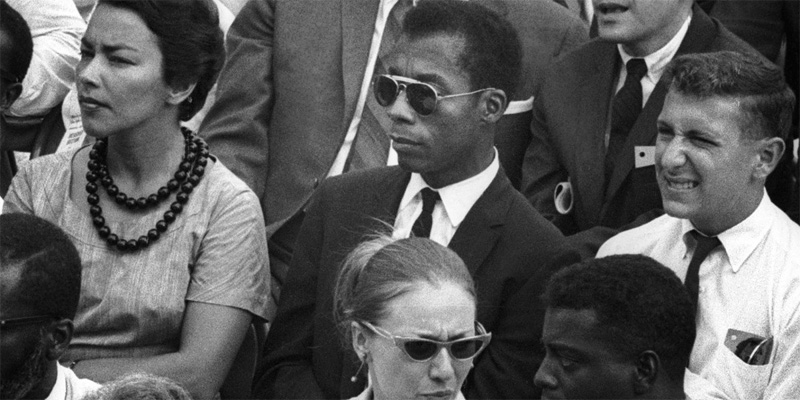

While Baldwin was widely known for being a major voice in the civil rights movement who marched alongside Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., a lesser-known fact about him was his enduring solidarity with Palestine and how he viewed strong parallels between Black and Palestinian liberation movements—united in their fight against oppression and imperialism.

In a then-controversial 1979 essay for The Nation, Baldwin wrote:

But the state of Israel was not created for the salvation of the Jews; it was created for the salvation of the Western interests. This is what is becoming clear (I must say that it was always clear to me). The Palestinians have been paying for the British colonial policy of ‘divide and rule’ and for Europe’s guilty Christian conscience for more than thirty years.

Baldwin had been writing about Israel-Palestine since the early 1960s, but his views changed radically over time. In his earlier essays, there is very little mention of Palestinians. It is in the late 1960s and early 1970s that, like many Black American intellectuals, Baldwin would become critical of Israel and supportive of Palestinians.

Nadia Alahmed, a Palestinian scholar, activist, and Assistant Professor of Africana Studies and Middle Eastern Studies at Dickinson, told me that “once Baldwin changed his mind about Israel, he never stopped criticizing it. Baldwin was one of the very first prolific black American voices to recognize Israel for what it really is.”

Although his self-imposed exiles in France and Turkey are well-documented, Baldwin also travelled widely in Africa and the Middle East. In September 1961, Baldwin was invited by the Israeli government for a tour of Israel, which was promoting itself as a post-racial haven intent on attracting Black American thinkers, like Baldwin, who felt alienated by their country’s enshrined racism and were looking for a new home.

According to research by Nadia Alahmed in The Shape of the Wrath to Come and Keith Feldman in A Shadow over Palestine: The Imperial Life of Race in America, Baldwin was—like many Americans—initially optimistic about Israel and the idea of a nation for Jewish people, a group that had been violently discriminated and traumatized.

Baldwin recounted in “Letters from a Journey” that he was treated like an “extremely well cared for parcel post package” by the Israelis in 1961, and that “Israel and I seem to like each other” upon first impressions. He visited the Negev desert, the Dead Sea, Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Haifa, and a kibbutz near the Gaza Strip.

But this romanticized view of Israel didn’t last long for Baldwin, who had grown up poor in Harlem and the grand-child of a slave. “Being a brilliant man and having grown up in the circumstances that he had grown up in, he could see the surveillance and the police state. He could see the police brutality against Palestinians. And he also says, ‘wherever we would go, there was always a border.’ He’s very acutely aware that brown and black Jewish people in Israel are second class citizens,” Alahmed said.

It was about a decade later that Baldwin started publicly adopting an anti-Zionist stance. In his 1972 essay “Take Me to the Water,” Baldwin explained why he refused to settle in Israel: “If I had fled to Israel, a state created for the purpose of protecting Western interests, I would have been in a tighter bind: on which side of Jerusalem would I have decided to live?”

In a 1970 interview with Ida Lewis, Baldwin even said: “I am anti-Zionist. I don’t believe they [Jews] have the right, after 3,000 years, to reclaim the land with western bombs and guns on biblical injunction. When I was in Israel it was as though I was in the middle of The Fire Next Time.”

With statements so taboo for their time, particularly from a well-known intellectual, Baldwin was unsurprisingly called anti-Semitic by many American Zionists and was censored by several media outlets. In 1971, Baldwin drew explicit parallels between Black Americans and Arabs, telling interviewer Margaret Mead: “You have got to remember, however bitter this may sound, no matter how bitter I may sound, that I have been, in America, the Arab at the hands of the Jews.” Mead then quickly shut down the interview and said that Baldwin was “making a totally racist comment.”

A lot happened in the world during the 1960s that incited Baldwin to change his mind about Israel-Palestine. Israel aggressively expanded its territory, notably occupying the Syrian Golan Heights and Egyptian Sinai Peninsula, and established itself as a military superpower after defeating three Arab armies in the Six-Day-War. Meanwhile, anti-Vietnam War protests coincided with Black Power movements in the US.

On a personal level, Baldwin was devastated after the assassinations of his friends Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. X—along with Muhammad Ali—was one of the loudest Black American voices advocating for a free Palestine at the time. In 1964, in Cairo, Malcolm X said that “the problem that exists in Palestine is not a religious problem… It is a question of colonialism.” That same year, one year before he was assassinated, Malcolm X had even visited Gaza, then under Egyptian control.

Baldwin agreed with Malcolm X’s claims of American hypocrisy—that when Jewish settlers in Israel act with violence they are praised by the West, but when Black people do they are attacked, jailed or killed. Baldwin wrote in a 1967 New York Times piece: “The Jew is a white man, and when white men rise up against oppression, they are heroes: when black men rise, they have reverted to their native savagery.”

Scholars said that what really changed Baldwin’s mind on Israel-Palestine (and introduced anti-Zionism to the American public) were the positions taken by the Black Panther Party and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Nadia Alahmed said that Baldwin’s conversations with Black Panther members Stokely Carmichael, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale about how Israel is an extension of American imperialism and a white settler colony is what “really radicalized Baldwin”. “The fact that Baldwin embraced the Black Panther Party was huge, because there were so many black critics of the Black Panthers and what they stood for,” she said.

Another prominent voice connected with the Black Panther Party and friend of Baldwin’s was Angela Davis, who became arguably the most important figure on Black-Palestinian solidarity. Baldwin would write to Davis while she was in prison in 1970, and Davis later recalled that she received support from Palestinian political prisoners and from Israeli attorneys defending Palestinians while behind bars.

Such stories of internationalist solidarity are still relevant in recent years. Prince Shakur, a young Black queer writer and activist heavily influenced by Baldwin shared how he became interested in Palestine during the Black Lives Matter movement in 2014.

“People were sharing posts online about ways to remedy tear gas canisters and resist police violence, whether it’s in the West Bank or in Ferguson,” Shakur told me. On the situation in Palestine today, Shakur added: “When Black people go online and see other people suffering in ways that are visceral and primal, and videos of violence get weaponized by the far-right, this process is very familiar to Black people.”

According to Michael R. Fischbach, the author of Black Power and Palestine: Transnational Countries of Color, young black Americans see these parallels easily, especially as a result of social media and the proliferation of movements like BLM and Boycott, Divest, Sanctions (BDS). “It’s part of the same struggle,” he told me.

With events to commemorate Baldwin’s life and legacy for his 100th anniversary planned in New York, London, Paris and more, many will pay tribute to Baldwin’s writing, but no-one ought to ignore his politics rooted in solidarity, which continue to inspire new generations across the world.

As Baldwin himself once wrote: “The paradox of education is precisely this — that as one begins to become conscious one begins to examine the society in which he is being educated.”