The List by Noreen Graf

We’re settling into the hot tub, me with my glass of wine, my 30-year-old daughter with some probiotic drink. She lives in my pool house with her husband whose birthday is today. He’s working late tonight as a server at the Coffee Zone, wearing an “it’s my birthday” sash to get better tips. I let them stay for free as long as they pay electrical, to make them accountable and curb their use of AC. All three of my daughters have moved back home for stints of time to reset and relaunch. This daughter is a struggling writer. These days, moving back in with parents is a thing. Not like in my day. When you left home, either booted out or running free, you stayed gone. Mom booted me. She’s been on my mind since last week when I stumbled upon her lifelong list of things that made her angry.

“Sometimes I worry you have Alzheimer’s,” says my daughter, yanking my brain back into the hot tub.

“Like when?”

“Just sometimes.”

I try to think of what I’ve done. Was it that she saw me playing Solitaire on my phone when she got home from work? How could she know I was at it all day? I haven’t played in years, but today I played while attending Zoom meetings with my audio and video off. I’m a Rehabilitation Counseling professor at a public research university that sits along the border with Mexico. But seriously, two back-to-back faculty meetings and then a department meeting with the dean. It’s grueling. Most times I garden on Zoom, but it was raining this afternoon.

My daughter glides her hands over the water, “It’s probably my anxiety about you getting older and dying.”

“I’m aging at the same rate as everyone on Earth.”

I try to reassure her, but I’m not reassured. A few weeks ago, I told my sister I always feel like I’m ready to cry, and I can’t figure it out. Maybe it’s aging, or professor burnout, or the phenomenon of cyclical live-in children… or my wandering brain. I’m sure my students have wondered about my lucidity during lectures that sometimes stray down adjacent dead-end paths only to do an abrupt about-face with a familiar, “Where was I?”

I assure myself they like these meanderings.

In front of the hot tub, Moby, my Great Dane, circles. Over the past eleven years, I’ve watched Moby’s face morph from a cool gray with a sharp white forehead stripe into an old dog face with racoon rings around his eyes, his stripe blurred by white hairs that cover all but glimpses of his original youth. But this isn’t about Moby.

Last week, my colleagues and I voted out our director. This was a personality thing more than a competence concern. We really didn’t have any power to enforce his removal; it’s the dean’s call but he allowed us the vote to assess faculty discontent. It also sent a message to the director, who resigned, effective immediately. So, for a day, we were unsteered. Paddles resting in a rowboat atop still water. I didn’t say it was calm water. Imagine waiting for a giant sea monster to spring up, mouth open, ready to gulp up the boat, the oars, and the disgruntled professors. Still water. The next day we had an interim director. Quiet chaos ensued, mostly in the form of gossip—and the kinds of meetings that might want to make a professor play video games all day.

I don’t think my mom ever got Alzheimer’s. Nothing to worry about.

In the hot tub, I tell my daughter, “I don’t think my mom ever got Alzheimer’s. Nothing to worry about.” Ultimately, I think parts of her brain slow-rotted a tad. I don’t tell my daughter this. On her deathbed six years ago, Mom got her four daughters confused. Not her four sons though; she recognized them until the very last.

At work, the monster in the still water is that now everyone feels “unsafe.” The result of our mutiny. Unsafe is a trigger word these days, a popular and dramatic overstatement. What we feel is insecure. These are insecure times. Who could be next on the chopping block? What we feel is replaceable (easily). What we feel is unloved.

Also last week, or maybe the week before—I have trouble with time—I was rushing through my home office, having lost my phone again, and I spotted a piece of paper folded in a decorative blue bowl on my very dusty bookshelf. I didn’t remember what the paper was. Why was it there? I stopped to pick it up.

My chemistry professor ex-boyfriend says I’m a cat, even though I’m a dog person, because I’m always getting distracted and changing directions whenever something catches my eye. I’m headed to the car, I start weeding, that sort of thing.

Maybe I should tell my daughter I’m a cat. She’s sipping her probiotics and telling me about critique of her TV script from a screenwriting competition she entered and I can’t keep my head on what she’s saying. I’m proud of her, and her love of writing, of putting words to paper.

Anyway, last week I opened the mysterious paper from the blue bowl and immediately recognized Mom’s handwriting. At the top, a title is written: Anger. It’s underlined because I believe in her day, titles were always underlined. If one of my students underlined the title of their APA-style paper, I would take off points. But maybe Mom was underlining for emphasis.

My daughter is checking her phone to see if the script contest results have been posted. I’m always losing my phone and dear Alexa wants to charge me for the Find My Phone function, apparently I have only two more free calls to locate my phone. My daughter announces she is in the quarterfinals for her queer superhero movie script.

“You go girl!” I tell her, but she’s texting with rapid-fire fingers.

Where was I? Oh right, the day I found the list in the blue bowl, I was chasing the sound of the ringer, because Alexa wasn’t charging yet. I was in a hurry. I can’t recall why. But, with my phone in my back pocket, I slowed to read the first statement on Mom’s Anger list. Unsupervised when with Carol and me killing her. I already knew this part of Mom’s story but was saddened nonetheless.

Before Dad died of leukemia in 2006, Mom spent years writing the family history. They visited Germany so she could write Dad’s ancestral history, and then Ireland to write her own ancestors’ stories. And then came a third book about her more immediate relatives (we’re talking starting in the 1930s here), which included stories about her growing-up years. She titled the book, What’s in your Genes? When mom mailed her spiral-bound books to me and my siblings, it was with an unspoken request to read her pages and pages of family history, adorned with black and white photos of some of the roughest, worn faces on earth (really, I’m related to them?). I certainly wasn’t interested, nor did I see the book’s relevance to my life. And I didn’t have the time for it, as I was trying for two academic publications a year with ever-diminishing enthusiasm.

My relationship with Mom hadn’t been great. Maybe it was being kicked out the night of my graduation from high school and our two-year estrangement after, all because of what boiled down to my rejection of the Catholic church—her life blood. But even after our mending, in her presence, I was frequently seething under my silence. Not silence as in quiet. Silence as in not speaking my mind. The silence that comes just before the scary guy jumps out and makes you shriek, and then he stabs you to death with the Halloween soundtrack getting louder and louder. Maybe I felt unsafe?

Mom died in 2019, just before COVID hit. But a couple of years before her death, when Mom was alone, I filled a wine ritual vacancy. Mom had called her sister nightly to share a glass of wine over the phone. When her sister died, I stepped in. Who else was going to listen to my stories of my three grown girls, dogs, and latest published academic articles and failed fiction? We talked about me for hours some nights. I would frequently clench and cringe at her opinionated responses, but then blather on and on.

I begrudgingly and dutifully (with a glass of wine in hand) read her book. Then one day, as I was reading page 33 of volume three—about Uncle Ed, Aunt Phyllis, Uncle Bern, Aunt Marg, and Aunt Lib who lived at 8136 S Peoria around 1939—and I read the line, “I murdered that beautiful child.”

I read the line again. Who murdered what child?

The shock of that line was like opening a pantry and coming face-to-face with a rat eating the dog food. This is more than a metaphor, it’s a memory. What could I do? I screamed and closed the pantry, so it wouldn’t escape. But closing a door doesn’t make a problem disappear. It gives you time. But you can’t take time because you know you have to deal with the rat. You can’t stand the idea of the rat being in the pantry, so you face it. I called Mom..

“I was reading your family history and…” Really, I can’t remember how I put it to her, but I later came to think, her whole purpose in those years of research and writing about ancestors was so she could write that one line, to tell her abominable secret. Here is an excerpt from page 33.

When I was 4 or 5 years old, Mom, Dad, Uncle Ed’s daughter, Carol, and myself were visiting there. Carol and I were sent to Uncle Ed and Uncle Bern’s bedroom to take a nap. Carol was 2 or 3 years old, and beautiful, like a Dresden doll. I believe she had long, dark curly hair and milky white skin. Instead of napping we were playing. We must have been playing “doctor.” In my mind’s eye, I see myself giving her a teaspoon of medicine. It was in a dark bottle and on top of one of the dressers. Where did the spoon come from? The bottle contained “Oil of Wintergreen.” She died! I don’t remember what happened next. Did she die right there? Did she go to the hospital? Did the police come? Was I questioned?

She only learned what substance killed her cousin when Mom was in her seventies. As a child, she never heard a word about the dead girl. She was never included in a funeral, and no one mentioned the incident again. It was poofed away.

I guess like our director has been poofed away, only he is still there as a faculty member, and I feel terribly sorry for him because I remember when I was poofed away—twenty years ago. Lesson to newbie professors: Do not have a public affair with your dean in the same year you are coming up for promotion and tenure. This was a tragic story, and I won’t bore you with the details. That dean resigned just before a vote of no confidence—there’s that voting against other faculty thing again. Obviously, I wasn’t tenured. Within a year, the dean and I married, only to divorce a year later, and then get new jobs in states far apart. I heard he remarried.

Lately, I keep driving by a sign in the yard of a neighbor a few blocks away from my home. It has just one word. Pray. And it lingers in my head.

The truth is I’m terrified of Alzheimer’s, of losing memories that shape my connections to the people I love. My irreverence lightens the weight of what time may take. But then again, I might just have the opposite of Alzheimer’s because I’ve been getting back memories of my childhood. I can’t recall any right now, but when I get them, I call my oldest sister—who recently tested negative for Alzheimer’s proteins.

Tonight, in this hot tub, the dog still eyeing us, I tell my daughter this genetic factoid and she says, “It doesn’t mean you don’t have it.” I’m annoyed, I would never have said harsh things to my mother, even in her later-day times of confusion.

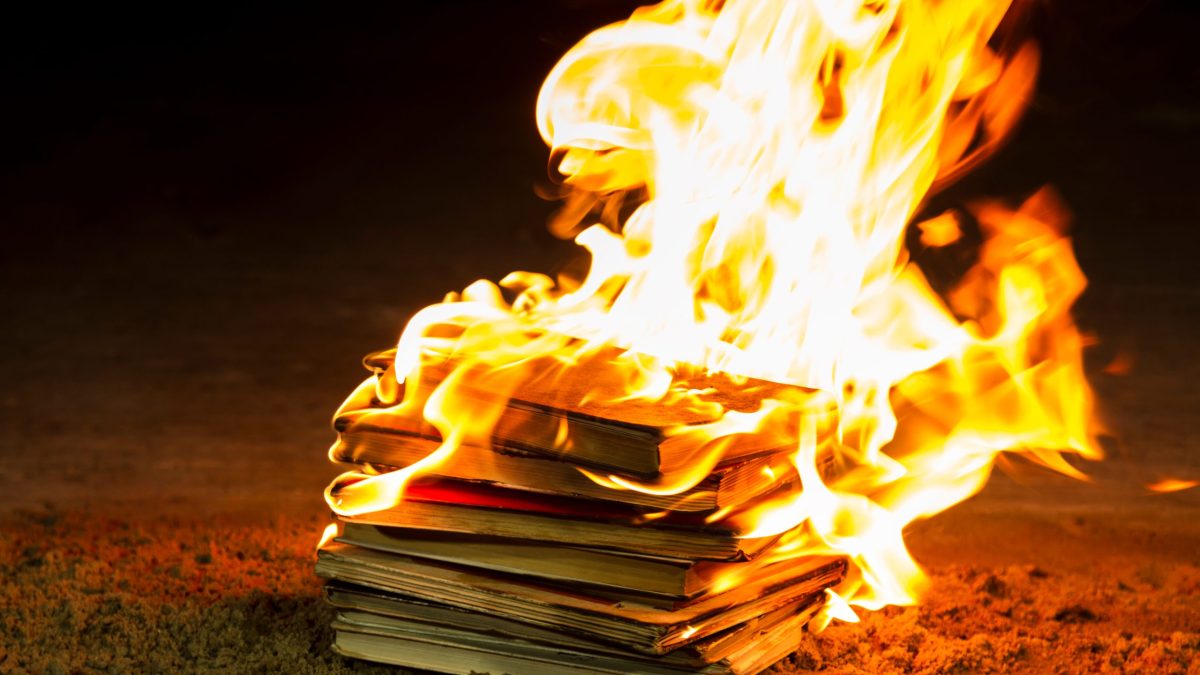

Aside from Mom’s ancestral volumes, she was a voracious journal writer. A teenage bride—18 was common I guess back in the day (I should talk, my first marriage was at age 19)—Mom kept journaling through having eight babies, starting in 1956, through Dad getting shot as a police officer in the 1968 riots on the south side of Chicago, through the killings of the Kennedys and King, and through our wine phone arguments about the man whose name rhymes with Rump. But I don’t care about those political arguments now. What I care about are the volumes and volumes and volumes of her journals which were burned before read. Poof. They were gone. Like she was.

Mom was best at expressing anger when I was growing up. I didn’t see her sadness, and she was, as I am today, uncomfortable with touch or expressions of affection. When that wall began to crumble as she aged, I couldn’t handle it, because my wall remained intact. I became expert at changing the subject when she approached emotional expression, trying to tell me what good things I had added to her life. I imagine she wrote them down.

When Mom died, her bookshelves were lined with her journals, maybe sixty or seventy. These books were the only place she had been free to fully express her feelings. A few days after her death, my eldest sister randomly picked up one journal and read a page aloud. It was something that Sister 1 interpreted as negative and about her. Okay, it probably was negative, and about her. Sister 1 decided she didn’t want anyone in the family reading things she told Mom in confidence. “Okay,” I said, “you read first and redact anything about you that you don’t want anyone to see with a black sharpie.” So, then some other sibling, I don’t remember which, said something like, “But then (Sister 1) might read something about me I don’t want anyone to see.”

All around the mulberry bush, the monkey chased the weasel. See, I told you, things are coming back from my childhood.

We all live the human tragedy. Every human.

As a grieving family, we decided Baby Brother 4, somewhere in his late forties, should take the journals and keep them safe and in a year, we could revisit this hot topic. I was hoping Sister 1, and everyone else would get to a place they just didn’t care who knew what about whom. We all live the human tragedy. Every human. They are the same tragedies, “there’s nothing new under the sun.” (Ecclesiastes 1:9). Old as the bible. See, I already know Sister 1’s husband is the scum of the earth, Brother 1’s second wife did a lap dance on some stranger at their wedding reception, and Sister 4 stole Brother 3’s girlfriend. We think Sister 3 set a fire. The thing is we all know, through our very efficient grapevine, most of the stuff we pretend not to know. And lots of stuff even Mom didn’t know. I think.

Sitting in the steamy water behind my house, the dog now stomping around in my tropicals, my daughter is agonizing about calling the doctor because it makes her anxious. “You should try not to worry so much,” I say to my daughter who has just told me about her stomach problems of the past week. I try to focus on her words and raise my body half out of the water by sitting on my heels. The hot tub is feeling hot, burning hot.

What I have of my mother’s words, besides the ancestral history volumes she wrote, is one sheet of paper titled ‘Anger.’

Burned. I think, burned. Two years (time flies) after Brother 4 was charged with the safekeeping of the journals, I asked about the journals and was told the books had been burned. I was told by Sister 1 and Brother 4 that everyone had agreed to this action. No, I said, I would never have agreed to it. When? No, I don’t have Alzheimer’s. If I were to somehow agree (and I didn’t), I would have insisted they be burned in a ceremonial way. I’m a counselor, or at least I used to be before I was a professor teaching counseling, and I know how to end things. I know, and teach, about closure, and there wasn’t any.

Another poof goes the weasel! I feel unsafe, or did I say that word is an over-exaggeration? Why aren’t siblings 3, 5, 6, 7 and 8 outraged?

So, what I have of my mother’s words, besides the ancestral history volumes she wrote, is one sheet of paper titled “Anger.” I’m centering the text, so it becomes a poem. Poems are sublime. She meant it to be read. She wanted to be heard.

Anger

Unsupervised when with Carol and me killing her

Never talking to me about her death

My mother on the bathroom floor drunk? Hurt?

Parents fighting-fighting

Dad coming home drunk almost every day.

Dad leaving us at a cottage

Hating the holidays because I never knew when they would fight

I never remember being hugged as a child

I think my mother resented the way Dad spoiled me

I think my Dad may have spoiled me to get at Mom

So late for my music recital

So many times caught between them

Daughter getting pregnant before marriage

Husband not telling me about not getting the chief’s job

Husband quitting work

Moving to Indiana and leaving me in Illinois

Husband moving out of our bed and giving up sex

Husband drinking

My failure as a mother, person, wife

Never controlling my temper

My own list of angers, failures, disappointments isn’t long if I condense them into qualitative themes with multiple sub-themes—I also teach Qualitative Research. They have to do with my poor human and dog parenting, poor partnering, and poor performance. The overarching theme is poor choices. But my biggest anger is that Mom’s thoughts, for her whole life, were banished by her own children and burned.

Moby barks to remind me of his presence, once again patiently sitting next to the hot tub. Such a loyal companion.

Not long before her death, Mom wrote down every item she owned of aesthetic, monetary, or nostalgic value on a slip of paper. With a girlfriend as her witness, one at a time, she pulled the slips out of a jar to randomly assign who of us kids would inherit each specific item. Her greatest fear was that the family could be torn apart by material things, and she wanted to avoid any post-mortem arguments.

But the journals remained in her house after her death for us to deal with. Unnamed beneficiary.

My daughter is ready to get out of the hot tub. I’ve inattentively kept up with the conversation about the doctor and writing edits and promised to finish reading her script tomorrow. Lack of attentive parenting needs to go on my list, sub-theme of poor parenting. But who knew parenting would go on for so long—thirty years and counting. That I would never be able to put down the weight of it. She walks away dripping and wrapping the towel around her still young body, her young, semi-trained service dog, Maggie, bounding towards her. Moby waits for me.

I sink my body down until only my face is above water. I close my eyes and listen to the humming from the motor keeping the water warm; underwater it is akin to white noise. I relax and imagine swimming upward in deep cerulean water. Then I feel panic. The water goes black, and I break the surface with my flailing breaststroke. I’m out of breath and gulp in air.

The thing at the top of my anger list is that I will never have the opportunity to read my mother’s uncensored thoughts. Or run my fingers across her practiced handwriting as I read her words. To push aside events of drama and trauma and hear her dreams and joys as well as disappointments and pain.

I want to wrap this up and provide a tidy end, where I make peace and come to terms with aging and colleagues and children and siblings and losing my mother. And I could do this because I am trained in writing discussion and conclusions sections. I could force some kind of forgiveness message to complement being in a hot tub with a glass of cheap white wine over melting ice because I like it that way. And too bad if ice shouldn’t be in Chardonnay. Instead, I’ll follow Moby inside. Maybe I’ll forget someday.

Poof.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.