Out of Body by Kristina Kasparian

Wanda is the technician today. She asks Ethan and me to wait in the hallway until Margot is ready. We make ourselves small in the corner where they’ve wedged two chairs for situations like ours.

The corkboard is covered with photos of ecstatic couples embracing their newborns. I shift in my seat, struggling to imagine our picture. I test variation after variation of who would be in the middle, holding the baby. It should be Ethan. No, it would have to be Margot. She’d want it that way, and it’s only fair. It won’t be me. I can’t take credit for any of this—not the egg, nor the womb, and certainly not the instinct. I’ve come to hate these clinic corkboards. They’re a shrine to our losses and to my selfishness. These mothers are not selfish. They’ve proven their resilience and earned their place. They didn’t cop out like I did. They’d never hesitate to call themselves mom. I focus instead on the fish swishing in slow motion in the aquarium.

Ethan is calm now that Margot showed up. We both feared she’d changed the appointment date and left us in the dark. She’s been leaving a lot in the dark lately and, as we scramble with the bits and pieces she lets us in on, our vision of being a team in this has begun to dissolve. His hand is warm and steady on my knee. My gut is still churning. I have to remember she wants to be good at surrogacy. I have to remember to breathe.

The door flings open soon after we sit. The displaced air smells like sanitizer and fresh linen. Wanda ushers us in but is unsure where to place us.

“You could go in the hamper,” I tease Ethan. Oh, everything I say sounds so awkward and dumb. Out of all of us here, I am the one who should go in the hamper.

I feel the cold gel on my belly as Wanda squirts it onto Margot’s skin. My brain bridges the gap between our bodies, like a magic trick. I look at Margot for a second. She seems flushed today. Panting, almost. Wanda starts clicking buttons.

“Oh my!” Ethan squeals. He sounds like an old man when he’s excited.

“Wait.” I elbow him. “Don’t look yet.”

“Why not?” he whispers back.

“Because Margot can’t see.”

Wanda realizes and pushes the screen towards Margot.

The gel on Margot’s skin traces the bend of my ribcage and pools in the small of my back. As Wanda zooms in, milky wisps appear across a dark cosmos, but I can’t make sense of the rest. It’s not my disease I see this time—not one of the unruly masses that seed and bloom in my abdomen—but a face and limbs and a pulsing heart in a spacious, spotless womb.

I can barely look at Ethan. I’m afraid to see just how much he’s beaming. I’m afraid of how much he’ll hurt if all this slips through our fingers again. But mostly, I’m afraid this will make him the happiest he’s been in the twenty-two years that I’ve loved him. Unlike him, I’ve yet to come to terms with all the ways our new roommate will shake up our lives and love and dreams.

“The baby is very active,” Wanda says as she clicks and measures. “But very cooperative!”

Ethan looks pleased, as though these traits are sure to stick.

“It’s the latte,” I say, and Margot lets out a forgiving chuckle.

I smile at the sound of it, craving the ease of our early interactions. When we first met Margot, it felt like we’d hit the jackpot of a once-in-a-lifetime connection, but the tension between us has mounted over the last few weeks. Our best intentions and cautiously chosen words constantly fall short with her, our care somehow getting lost in translation in the haze of hormones. Her outbursts and withdrawals are triggered so abruptly, with little reprieve between episodes, leaving Ethan and me scrutinizing our texts to figure out exactly when we set her off, why we’re so bad at this, and how to make it right.

Margot is filming the screen, the way she does when we aren’t in town for these check-ups. I’m surprised she documents everything just as much for herself as for us, but of course she does. Why shouldn’t she? This is also her story—intertwined with ours, yet its own separate thread. I take it as a reassuring sign that she’s not detached from this pregnancy, that surrogacy is still a source of pride for her and not simply a business transaction.

‘During the pregnancy you’ll be a spectator.’

I notice I’m not filming or taking any pictures. I make a half-hearted reach for my backpack that I’ve wedged between an IV pole and a cabinet, worried that Margot will assume I don’t want this enough, that I’m ungrateful and unworthy of her womb. It’s just that I’m not used to being excited in medical settings. I’ve learned by now that all progress is fragile, and I’m praying our pieces won’t land on a space that sends us back to start. I don’t want to fiddle with my phone. I don’t want to miss an ounce of this moment that Ethan and I never expected to be wrapped in, this moment where my life is beginning and ending and standing still.

And, besides, if she’s recording, I don’t have to. I’ve grown used to following Margot’s lead. I’m hunched against the wall, but I know that’s where she wants me.

“During the pregnancy, you’ll be a spectator,” Margot warned us very early on, drawing the delicate boundary between her pregnancy and our child. This is our first surrogacy journey, but we are Margot’s third parents. We’d wanted an experienced surrogate, and that seems to come with being told how things are done. The rules of engagement are as she explains them to us. The agency we hired to match us doesn’t provide us with much support, aside from sending out annoying funnel emails and dispensing the funds we’ve put in their trust.

The trouble is that spectating is hard work when a history of medical neglect and grief have wired you to be protectively proactive. Spectating feels next to impossible when you are bursting with gratitude and guilt for having asked someone to be pregnant for you, to risk their health while you safeguard yours. Spectating seems absurd when you’ve displaced entire universes and gambled fortunes to create this reality where the stakes are unbearably high. Still, I’ve been trying hard to spectate, to make myself patient and compliant and calm, even though I’m yearning to be all in, to savor this unusual pregnancy in my own way.

Behind the irritating fabric of my face mask, I am breathing through my teeth. I glance at my grinning husband, who hovers over the ultrasound table no differently than if it had been my body, my belly, my baby. He’s not feeling as out of body as I am.

I’m staring dazedly at the white and the shadows, the moving inkblots, this body I’ll hold in my mom’s rocking chair in the thick of the night, and I’m swallowing hard, beckoning myself to feel anything but removed.

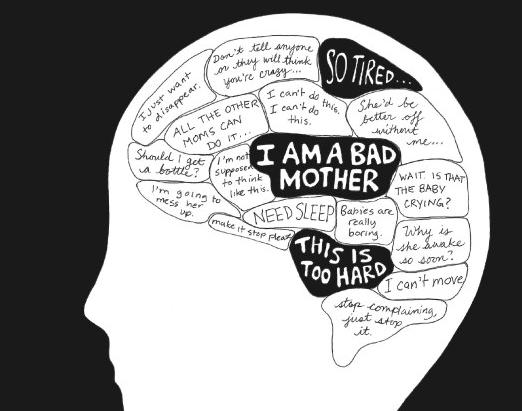

But I am the other in mother.

“Honey, I need you to put yourself back into the equation,” the counselor told me last week. “It’s not your egg, you’re not the one carrying the baby, and you’ve already lost so much of yourself and your career to this relentless illness. I need you to start taking up more space and getting your confidence back. Your needs matter as much as hers, please remember that.”

I was in my twenties when I found out my eggs were faulty, not because Ethan and I were trying to conceive, but because of the hot flashes and fatigue that had suddenly piled onto the searing pain and hemorrhaging that upended my days as an ambitious graduate student. Though I’d seen over a dozen doctors since my late teens, no one would name the illness that had been steadily dismantling my identity. The onslaught of these new symptoms only veered us further away from the mark; suddenly, we found ourselves discussing premature menopause and egg-freezing instead of getting to the bottom of my illness. At the time, menopause was even less on my radar than motherhood, yet we somehow found ourselves pulled into the rabbit hole of fertility treatments because doctors urged us to prioritize pregnancy. The high doses of IVF hormones only fueled the disease until I could no longer shower without vomiting or stand up after peeing. After repeated miscarriages, I pulled the plug on pregnancy to save myself. I was told I was too young to give up on my eggs and my uterus, that there was still more we could try to make a pregnancy stick. But after five surgeries in eight years to try to keep my finally-diagnosed illness at bay, I wasn’t willing to take that risk. As much as I’d have loved for Ethan to finally be a father, I didn’t want to be a mother at the cost of my body and mind. Surrogacy is our most tender compromise, a decision that felt liberating as soon as we’d made it.

Surrogacy is our most tender compromise.

But at some point along the way, Margot’s confidence began to chip away at my own, as though they belong to the same pie chart. I’ve been struggling to keep up with this acquiescent tango, this push and pull between showing support and giving her space. The moves change as soon as I learn them. I’ve been walking on eggshells and second-guessing my facts, erasing my wants just to keep the schedule, the trust, the peace. It feels like the least I can do in return for such an impossibly tall ask. After all, the doctor had given me the option to carry, and I chose not to take it. I chose to assign someone else that weight.

Now, my eyes on the screen, I think of how I might remember this moment when that face finally looks up at mine. I think of our donor, Bettina, who is somewhere going about her life, not knowing her egg has hatched inside Margot’s womb. I think of my grandmother and wonder when I’ll finally find the right words to tell her—in my heritage language that lacks all these controversial scientific terms—without dishonoring her vulnerable values and sacrifices. She raised me to do everything myself and to silently push through pain, and here I am outsourcing the very essence of what makes a woman worthy. I think of my teenage self and want to tell her we’re still ambivalent about motherhood, that we didn’t grow out of our reluctance like they’d promised we would, that we acquired a taste for asparagus and yellow gold and winter, but not for pregnancy. I think of when the door will slam on the words, “You’re not my mother!” and I wonder who, by definition, is: the one who reproduces, the one who births, or the one who soothes?

“Baby’s facing you now,” Wanda says to all of us as she presses and probes.

We all lean a little closer to the screen. The three of us are in this being’s gravitational pull—already, forever.

“Oh, hiiii!” Ethan exclaims, making Margot and me giggle.

Am I a fraud for being happy right now, when I’ve never craved kids in my kitchen? What kind of selfless mom will I be, if I’ve already put myself first? I’m sure I won’t be a natural at parenting like Ethan, but I’m curious about finding my own flow. Margot told me last month that I don’t have the faintest clue of the life that awaits me. On her bad days, she mocks my work and my slow mornings, tells me I’m in for a major reality check. I remind her—and myself—that living with a disabling illness has made me creative with my time and energy. I try not to let her rattle my faith in my adaptability, but she does. When I read her messages, I feel seasickness swell behind my sternum, yet it’s not from an embryo growing inside me.

Margot still hasn’t glanced in our direction. She’s propped herself up on her elbows and even her shoulders are turned away from us now; I can see the looped drawstring of her gown interrupting her hair’s strawy lines. We may as well not be in the room.

“Why would anyone choose to be a surrogate? What’s in it for her?” Our friends and family try to understand our arrangement. Their burning questions are also mine. I once told Ethan that I could understand murder, but not this. Margot says she grows babies well. She thrives on being needed and valued. Her happiest days are those where she receives compliments about any positive difference she makes and about the boys she’s contributed to the world. She fiercely defends surrogacy and educates unknowing or opposed minds who condemn the practice of renting a womb or buying a child. But, in recent weeks, as our involvement is kept to a minimum, I can’t help but wonder if she also likes the rush she gets from the power she holds, and whether it is reasonable for expert surrogates to feel this way. When we learn that our agency has been refunding expenses unrelated to surrogacy that are not in our contract, we feel we have no choice but to turn a blind eye to it all, partly because Margot often tells us she’s under financial stress as a single mom, and partly out of guilt from a culture that lauds surrogates as altruists and chides intended parents for being petty.

I’ve been thinking of how our dynamic may have been smoother if Ethan and I were a few time-zones away from Margot or if our hardships hadn’t programmed us to cling to every milestone. I think of all the people in online support groups whose need for a surrogate is more absolute—women born without a uterus, or women who gave up their uterus, or gay men. Maybe Margot would have felt more at home with one of them, where the roles are more clearly defined.

I’ve also wondered if it might have been easier if we’d remained strangers like with our egg donor, Bettina. We barely know anything about Bettina, only her medical history, basic personality traits, and the color of her eyes, hair, and skin. But surrogacy huddles you real close, real fast, and leaves no stone unturned. With Margot, we know what her weeknights look like, what her son cooks for supper, whether it rained during soccer practice, how her grandmother is doing. We know she’s a space optimizer and a note leaver and that she is unstoppably generous with the people she chooses to love. We’ve debated every opinion from abortion to cilantro. We know what pushes her buttons and how she pushes ours. It’s ironic, though, to know all this yet not have the slightest idea of how gracious the other will be in times of heightened stress.

I hope I am worthy of Margot’s sacrifices, of what she calls her pincushion butt after the countless injections of progesterone, of her six-hour drives each way to the clinic, and all that time away from her sons just so she could grow ours. But I secretly hope she’s worthy of our sacrifices, too.

When the ultrasound is done, the machine spits out a series of black-and-white photographs. Wanda grabs the roll of prints and tears it right in half. Three for Margot, three for us. This little white blob with a button nose is now safely tucked in each of our pockets.

Outside, squinting in the hot autumn sun, we catch up on our weekend plans on the curb, our voices tentative but possibly tender. We hug. In a few seconds, we’ll part. Margot has to rush back to her family, and we have to contend with this abstract concept of our baby growing somewhere far away from us.

In six months, it may hurt just as much for her to watch us walk away. Even the strongest threads look scraggly and strange when pulled apart from their weave.

Ours is the only car on the road, or at least, that’s what the fog has us thinking. We are pulled into the dreary haze by white ribbons of lane and snow. I never imagined my son would enter such a monochrome world.

I keep checking the ETA on the map, hoping we’ve timed our four-hour drive right, unsure of how fast or how slow delivery might be when it’s the fifth. Margot hasn’t opened our text in hours; she’s either sleeping, driving, delivering, or upset.

“You’re still okay without music?” Ethan asks.

“Mmhmm,” I nod, my eyes glued to the incrementally appearing ribbons.

The silence follows us into the maternity ward of the small-town hospital, where the hum of the cleaner’s floor zamboni is the only sound that reaches our ears for a long while. There are no beeping machines, no code blues or yellows or reds, no pages for doctors or patients. Occasionally, we hear sneakers shuffling past, a soft knock, a startling racket from the ice machine down the hall, and—finally—a muffled scream that culminates in sweet baby wails. This hospital makes delivery seem relaxing, at least for those who get to take their baby home.

Once, we hear, “We’re going to the O.R.!” Ethan and I look at each other with widened eyes, fearing it’s about Margot. The nurses have placed us in a sort of conference room to keep us out of the way. Margot wants to deliver alone, but we’ve been assured she’s agreed to have him brought to us right away. We aren’t told when she’s been induced or that the process has been delayed or much about her progress at all, to protect her privacy as the patient. I spend the wait staring at a box of luer lock syringes, and Ethan corrects some of his students’ exams. I don’t know how he can focus.

I don’t know how we’ll go on.

Now and then, we’re checked on by Sasha, a nurse whose eyes fill every time mine do. No one knows what to do to soothe us, and the social worker is not in on Christmas Day.

When Margot broke the news last week that his heartbeat had been gone for days, I was foolish enough to think we’d grieve together. Instead our trio collapsed like a house of cards. I’ve been desperate for more empathy from her all week, all trimester—something, anything, beyond information being relayed to us after the fact—but maybe that’s another impossibly tall ask. She dropped the bomb and retreated, keeping us out of the loop to block us from being here to say goodbye. The hospital didn’t even know it was a surrogacy pregnancy until we told them we were coming. I wish our lawyer would answer the phone.

Sometimes, the staff expresses their sympathy in stats:

“This is our first surrogacy loss in the seventeen years I’ve worked here.”

“After week twenty, the chance of a loss is actually lower than one percent.”

“It’s common for parents to choose not to see the stillborn, so there’s really no wrong decision here.”

I’m drowning in plain sight.

When evening falls and we’re told she still hasn’t delivered, it becomes clear we’re not driving home tonight. Sasha escorts us into a room at the end of the hallway so we can get some sleep. Margot and the c-section patient are in the only other occupied rooms. Margot’s door has a purple butterfly on it.

“You won’t forget about us in here, will you?” I ask. Understaffed big-city hospitals in our province have left their scars on us.

“No way,” Sasha laughs. “My shift ends in an hour, but I’ll introduce you to Lauren, the night nurse, before I leave.”

This is it: the closest I’ll ever get to being a new mom in a delivery room.

Ethan falls asleep a minute after I decide he needs the bed more than I do. I sit on what I don’t realize is a pull-out and peel one of the five clementines I’ve brought. I’m so stupid: I brought a muffin and a clementine for Margot and each of her two sons, in case they’d be here too, in case we’d be waiting together. I look around at the discordantly cheerful decor as my chewed-up nails dig into the acidic peel. This is it: the closest I’ll ever get to being a new mom in a delivery room. The first time I was in a maternity ward was nine Decembers ago, when we’d given IVF a try with my own measly eggs, and I’d ended up hospitalized for internal bleeding hours after the egg retrieval. The last time I was in a maternity ward was four years after that, when I miscarried our last viable embryo. Now Margot is miscarrying for me because I selfishly opted out, to protect myself from exactly this.

I put my hands over my ears. I swear, this silence is going to engulf me.

Ethan is on his side, his head slightly turned to the sky, like in a painting. I watch him breathe. I don’t know how he can.

The sudden break in the silence jostles us both awake. I scramble for my face mask and my glasses and to remember where I am and why my boots are on.

“She just delivered,” the doctor says, standing in front of us for the first time all day. I glance at my watch. Hours have passed—it’s one a.m. There are no sweet baby wails filling the hall.

“Is she okay?” Ethan asks.

“Yes, she’s fine.”

“Did she need surgery?” I fire next. Margot had been terrified about this possibility.

“No, everything came out. No tissue was left behind.”

Ethan asks what has been weighing on both our minds. “What was the cause?”

“I can’t tell.” The doctor shrugs his shoulders, and it makes me want to shake them. “There was nothing obvious I could see. We can send the fetus for testing. They can check the cord and the placenta and the development of the organs. It might tell us more.”

“Yes, we wanted to ask for that,” my voice croaks.

Asking for that involves signing a bunch of forms, including forms that list Margot as the mother and forms that transfer Margot’s motherness to me. We would have signed all of these same forms in a few months, on Mother’s Day weekend, together, while tulips pierced the dormant earth. A stillbirth is still a birth.

The extra forms we wouldn’t have had to sign—if the universe weren’t so sickeningly cruel—are the ones surveying where we stand on horrific things like an autopsy and a cremation and a memorial.

“What did you decide about seeing Baby?” Lauren, the nurse who replaced Sasha, puts her hand on mine. She briefed me earlier on what I might see, how discolored and deteriorated he might be.

“Yes, I still want to…”

“I don’t.” Ethan gets up to leave the room. “I have the last ultrasound so clear in my mind, and that’s what I want to remember.”

He leans into me before he goes. “Good luck,” he whispers. He knows I need to stare pain straight in the face and let it ravage me before any healing can ever begin. We are both fluent in grief, we just speak a different dialect of it.

When the nurses return to the room, my baby is in a large metal bowl covered with a sheet. I have to fight back nausea and the thought that I might never use my baking bowls again.

“Would you like to move to the bed?” Lauren points and I look over at it.

I bow my head and shake it. What I want to tell the nurses but don’t is that the bed is for real moms and their real babies, the ones who cuddle and cry and come home with them. The bed is for when the universe gives me a chance to finally get this right. Clearly, hope is a subscription you can never cancel, one you get billed for without informed consent.

Lauren brings him to me. Half-baked, lost forever. My mind crosses to a dark place where I imagine him suddenly gasping for air, changing his mind, sticking with us three. He can survive out of body, can’t he? He is scarlet, almost translucent. But it’s his slender fingers that shock me most, that remind me of how far we’d come. If it wasn’t meant to be, there’d been ample opportunity for it not to have been. A bad embryo, a failed transfer or two or three, Margot’s early blood clot or COVID infection. We could have not met her in the first place, or never signed the contract after our first conflict. But everything had worked, and in record time, for once. What was there to learn? Must there always be something to learn?

I stare at him, my little red frog. I already know I’ll never recover.

“Why’d you abandon us? Didn’t you want us? Did I take too long to decide I wanted you?” I want to wail these words and crack the eerie silence of this place. But my chest is too waterlogged, and I am sinking too fast to scream.

Lauren watches me watch him. “I can leave you alone with him for a few minutes,” she says.

When she starts backing away, I panic. “I don’t think I can…” I begin to howl, ugly and tired, folding in on myself with my clenched fists pressed against my empty belly, worried that Margot might hear, that she’ll resent my grief for burdening hers, the way she’d always lash out at us for adding to her stress and schedule.

“That’s absolutely okay.” Lauren gently tugs my baby away from me, and I sneak one last quick glance, already regretting cutting our time short, already wishing we’d said yes to cremating him.

I want him so bad, but differently. Not like this, not in the dead of winter. I want him warm against my chest, cooing and drooling and farting. I want him in the wee hours of the morning, before the robins stir awake. I want him hanging off me in the carrier, his face tucked under a yellow broad-rimmed hat as I dig my hands in cool soil and plant our abundant garden. I want him fiddling with his toes on the bed between us, intriguing our cat. I want him smooth and even and breathing, not this scary scarlet of stillness. I want him the way millions of people have somehow been able to have their babies without so much as a second thought. I want to tell him I’ve been waiting, that I cleared out so much space for him in my closet and drawers and heart.

I am hovering somewhere above this scene, ice-cold and see-through.

I can easily recall his knees and nose, but I have no information about his dimples or daydreams. How can I mourn someone I never even knew?

Ethan comes back in once I’m alone again. I remove my boots and lie on the bed, then eventually get cold and tuck myself in. There’s a clunky pad on the mattress that gets tied up in my calves every time I turn. This would be useful for my periods, I think. But this is for Margot and for mothers who deliver.

I wake up to the zamboni purring as it makes its way down the hall. The fog is back. Margot is gone. Her purple butterfly door is wide open, and someone is making her bed. They kept us apart from start to end. We didn’t see her, or half see her, or even overhear her. We’ll never meet again. I want to fall to my knees and scream at this colossal failure of ours. I imagine her driving, resolute, hopefully not bleeding. She’s free, yet we’re still here, bewildered and empty-handed. There’s no way she, or we, would try our foursome again. We’ll have to restart the long search for a surrogate and hope our holes won’t make us unlikeable.

How did we lose everything in half a heartbeat? Our son, seventy thousand dollars, our future, a friend. I want to wake up Ethan and tell him our life is over. I make some noise, and he comes to.

After more paperwork and more back-and-forth about whether or not we are parents, we leave. We walk past the Christmas tree trimmed with baby bonnets and birth photos—a red box of bereavement mementos tucked under Ethan’s arm—and let the fog haul us home.

I can feel my pulse just above my ankles. I’m surprised I’m alive.

My head is too buried in my pillow to even see outside. There’s no point in moving. My watch says it’s past ten, but I hide the evidence under covers. I can’t remember the last time I slept this much. Maybe after my first surgery. That was a january too—a slate wiped bare, much like this one. All I’ve found the energy to do is clean and declutter, as if to have control, as if he’s still coming.

The earth has gone flat, and I’m sliding off it fast, about to crash face-first.

“Five more minutes,” I lie to Ethan. He’s been up and about for who knows how long now. I’ve ignored coffee brewing and bacon sizzling and negotiations with a hungry cat. I’ve ignored my full bladder, which is starting to seize and cause a migraine.

“You can have seven minutes if you want,” I hear him say. I almost smile.

It’s been twelve days since the hospital. We’re at the cottage we rent from a stranger-turned-friend, on a tiny lake, cocooned by a vast forest that has become my confidante over the last four years. We come here once every six weeks to fill our lungs and journal pages. Nearly every one of our recent milestones has unfolded here, wrapped in the magic of loon calls and stormy sunsets. Now, the magic has no way to reach me—I am looking without seeing, and my heart has barricaded all its rooms. When I stare out at the trees, scouring the space between them for deer, I know I won’t see them—the animals keep their distance when they sense that I’m unwell.

I finally force myself into the shower. When the lavender foam flows past my navel, I think of Margot’s rounded belly and stretchmarks. I think of the umbilical cord. I almost envy them. I have no feedback from my body about this loss; it is unscathed, and I am unentitled to this grief.

A real mother would be entitled to know why her son died. The autopsy results are in, but we are not privy to them, though both our contract and the hospital paperwork state in black on white that the baby’s results are to come to us. We’re told they’ve discussed the findings with Margot, but she’s prevented staff at all levels from sharing them with us, and they comply because she is the patient. It’s unclear whether she is punishing us or concealing something. We fester without answers, discarded by doctors and nurses and counselors who have forgotten that we are the parents. I can’t sleep without being tormented by the same nightmare of Margot pushing all the air out of my chest with her hands and mine serving her coffee the next morning while I ask her if my music is too loud.

I wish it were the summer, when I wouldn’t have to feel the crushing weight of beginning a new year this way while scrolling through endless recaps and resolutions. This is a time for dreaming and anticipating, but I can do neither. Luckily, cell reception is spotty at best, so I can take a break from the internet for a while and from compulsively refreshing my email for results that won’t come.

At least in the winter, we can go two whole weeks without seeing another face out here. We can take a break from whispering thanks to everyone’s sorrys. They tell us they can’t imagine what we’re going through, but the truth is that we can’t imagine it either—we shake our heads in disbelief at least once an hour. “I’m lost,” I keep saying, then sobbing. I’m usually good at channeling pain into action when the universe slaps me hard across the jaw, but my life has just been emptied like an unzipped suitcase flipped over onto a bed.

When I manage to get dressed, Ethan and I take our daily walk through our favorite forest. We have to concentrate as we traipse. The snow is not deep, but there are a lot of fallen trees. Last spring, just before we matched with Margot, a tornado ripped through the forest, changing it forever. For three seasons, we couldn’t even enter—it was dangerously unstable. Being severed from my calming source hurt in a deeply disorienting way. Now, the path we knew with our eyes shut is playing tricks on us. How could something so entrenched in me have become so unrecognizable? As we crawl under fallen pines and trace wide berths around the messier trunks, we find ourselves unbearably unsure of the way. We stomp in the snow to make exaggerated footprints and lay down arrows made with branches to tell our future selves how to get out before we go any deeper. It’s always smart to have an exit plan.

Once we get through the tough bits, we walk quietly for kilometers. For hours, I focus on putting one foot in front of the other. Ethan walks ahead, stopping now and then to warn me of ice hiding beneath the surface or to hold branches away from my face as I duck through trees. My lips collect snow, wool, and tears. They’re not all from the cold.

As awful as these days have been, I know the apex of this grief is deferred. It’ll hurt way more in May, when the spring is utterly different than we planned, when friends who were pregnant alongside us get to bring their babies home. It’ll hurt more in July, when it’ll still be the two of us at the pool and the park. It’ll hurt next Christmas and forever, in the pauses between our sentences and the time it takes for our chests to refill after a fit of laughter. I’m no stranger to due dates deleted from my calendar, yet this grief is unlike all the others. We’ve been knocked out of orbit; what was so close will take an eternity to align with again, that is, if we ever muster the courage and finances to start over. I don’t believe in altruism anymore. The most benign personalities now plague me with doubt.

Every few minutes, I stop to let nature drown out the sound of us. I lean into the forest’s familiar embrace, though I have nothing to give back. I listen to starlings cackle and skinny trunks creak in the wind. The seasons will go on, whether or not I let joy back in.

I lie on my back in the snow. In my attempts to tolerate winter, this has become a tradition, but I didn’t expect to want to do it today. I stretch into a star and let the firm earth steady me. It’s as grounding as I’d hoped, like curling up against my mom’s chest as a toddler, like coming back home to my body. I watch the confetti swirl and the treetops sway. I need a sign, I tell my forest. I need magic to force my heart open a crack and show me that he’s not far and that we’ll be okay.

I get back on my feet and we pick up our pace; we can’t have the falling snow fill in our footsteps. Besides, it’s nearly three, and these days I’m only stable between noon and two.

As Ethan unloads the car, I open our mail. Half of the cards contain holiday wishes; the other half tell us we are not alone in our grief. Either way, I’m grateful for them.

I switch on all the lights and the lanterns, turn up the heat in all the rooms. I check on the plants. They look badly strained, but maybe not lost. I’m unsure of whether to water them, and how little or how much. I’ve become unsure of everything. The one in his room—the bonsai we adopted the day we chose his crib—is sprouting a new offshoot, its course clearly charted to the sun.

The end of this stark winter is intangible, but if the plants know where the light lives, I suppose I can look for it too.

The post I Am the “Other” in “Mother” appeared first on Electric Literature.