I had a little bird

Its name was Enza

I opened the window,

And in-flu-enza.

–1918 children’s rhyme

*Article continues after advertisement

It was a web, a net, spreading wide and enmeshing every sort of cousin and dependant and old retainer.

–Virginia Woolf (“On Being Ill,” 326 version)

*

During the early morning of March 4, 1918, three men in Kansas dipped into an acute fever, forcing them to step away from their military duties. Stationed at Camp Funston, private Albert Gitchell, Corporal Lee W. Drake, and Sergeant Adolph Hurby endured a deluge of symptoms: a roaring headache, a suffocating sore throat, and extreme muscle pain. With hollow cheeks, their bodies were soaked with perspiration, an effect meant to cool their shivering bodies, as they slowly fought a pathogen. Gitchell, an army cook, alongside other chefs, nourished thousands of the soldiers at Funston, while Drake and Hurby prepared a young generation of men who were drafted into the US military.

Camp Funston, a training ground for fifty thousand soldiers and a detention center for pacifists who refused to fight, sat on an alluvial plain adjacent to the Kansas River in the town of Fort Riley. Far remote from the bustling ports of the northeastern corridor, the sluggish creeks passed through this midwestern town, where American men deployed from Illinois and Texas were transferred to prepare themselves for battle in the First World War.

When the three men admitted themselves to the camp’s infirmary, medical staff sprang into action, attending to their needs by measuring their temperature and monitoring their affliction. Once the camp medical officer confirmed that these men had influenza, they were sequestered. Later that day, however, over a hundred men pulled themselves into the military’s clinic, seeking reprieve from the flu virus. By the end of the month, Camp Funston established an emergency hospital for a thousand of the army’s servicemen, hoping that the disease would settle. Whether they were wholly aware or not, the men at this camp were harbingers of the 1918–1919 flu pandemic that swiftly affected many of the people at the base and across the world.

Influenza wasn’t a new disease; instead, the conditions of the early twentieth century, which put a higher number of people in close proximity, increased the opportunities for the flu’s circulation and unsentimental wrath.

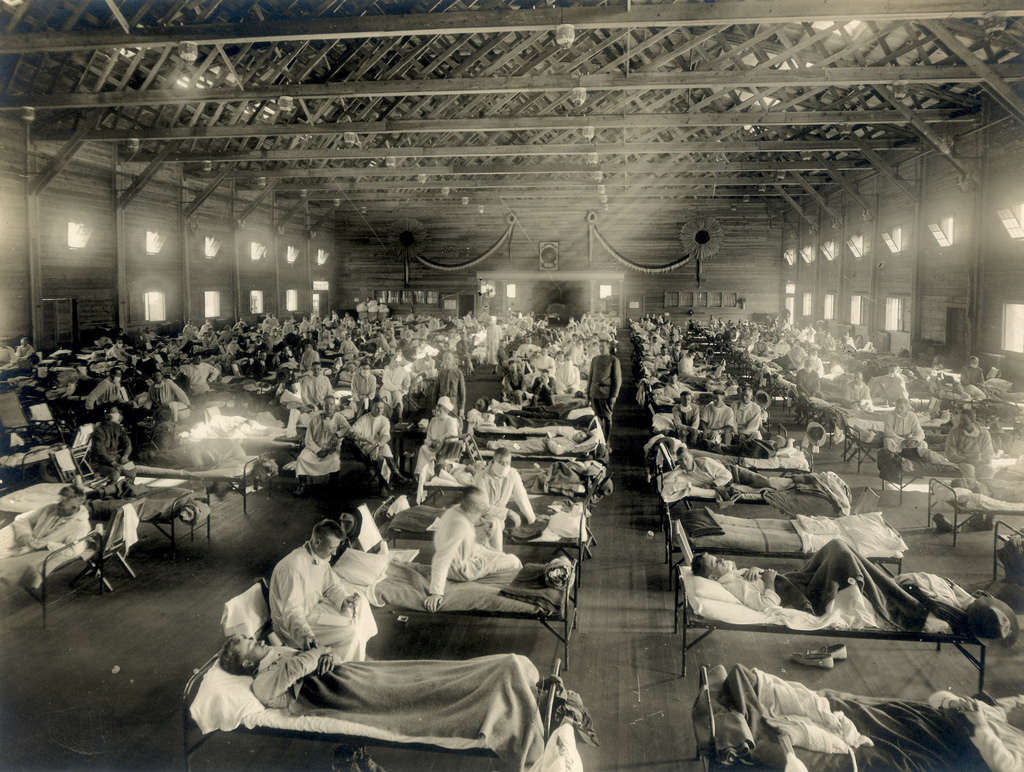

By the end of March 1918, over six hundred of the men at Camp Funston became ill with influenza, with many of them incapacitated, unable to carry out their service duties. Like Gitchell, Drake, and Hurby, many of them felt wretched from fever, muscle pain, and inflammation. As the week carried on, flu patients could experience sore throat, a runny nose, and the loss of appetite. Some men complained of abdominal pain, and others vomited uncontrollably. Other soldiers lay stricken, with their faces sullen, their airways obstructed by their mucous membranes. As the number of indisposed men grew, the military set up a communal sickroom, an infirmary that had been converted into a makeshift hospital where young soldiers lay near-comatose on angular cots, wrapped in pillows and linens. Staff began to don protective gauze face masks, as the recently able-bodied young men languished, incapacitated not by the expected war that had brought them to the camp, but by an invisible predator in their midst.

If photographs sharpen our understanding of the past, the image of the emergency hospital in Camp Funston unearths the unsettling consequences of the 1918–1919 flu pandemic. What seems like a grainy and visually dull picture brushes against the gravity of the disease. For the military men, the outbreak wasn’t merely a solitary illness, where they could recover in silence; it was visibly charged; a collective state of agony. When a US military officer took a profile picture of these men in their sickbed, it affirmed that even the strongest men could be subdued by a virus.

Photograph of military patients at Camp Funston, Kansas, taken by anonymous army photographer in 1918. National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Photograph of military patients at Camp Funston, Kansas, taken by anonymous army photographer in 1918. National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Although the image was anonymous (the photograph is credited to an unlisted military officer), the rows of beds expressed the scale of the outbreak and converted the private consequences of mass outbreaks into a public spectacle.

Camp Funston was the first, but not the only, US military base that dealt with the flu pandemic. In September 1918, approximately ten thousand soldiers at Fort Devens—near Boston—contracted the virus, resulting in dozens of deaths. Built in 1917, Camp Devens, like Funston, served as a training ground for drafted soldiers who were funneled into the First World War. By the end of the month, over 10,000 of the 50,000 soldiers reported flu-like symptoms. A doctor who treated influenza patients wrote to his friend about the outbreak: “This epidemic started about four weeks ago and has developed so rapidly that the camp is demoralized and all ordinary work is held up till it has passed.” Despair was rampant, but it was not the only response by the public. His testimony was neither original nor profound, but it spoke to the confusion and terror that became part of civil society.

Later, between 1918 and 1919, fifty to one hundred million people died of a new, even more deadly strain of influenza—some reportedly within hours of contracting the illness, others within days. The socioeconomic fallout was immense: garbage collection postponed, farm workers forced to delay their harvests, and businesses forced to close their doors. Given the loss of labor from war and disease, the United States experienced a mild economic recession during this period.

Frontline physicians toed the line between resilience and abrasion, sometimes unable to provide optimal care. Not only were health workers at exceptional risk, but they were also overworked. A December 1918 article in the Bulletin of Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania noted: “If the work at the main hospital was strenuous and heart-breaking, the work at the ‘front,’ meaning Front and Ellsworth Streets, where our emergency ward was established, brought us very close to the realities of war.” Founded in central Philadelphia in 1850, the Woman’s Medical College was the second oldest medical institution in the United States that trained women in medicine. As the historian Ellen S. More notes in her article, “A Certain Restless Ambition,” although few in number, American women physicians who served on the frontlines of World War One attempted to assimilate into their professions by exercising efficiency in care. On the one hand, that meant fighting a war but on the other hand, that included documenting how the influenza outbreak—at home and abroad—left people forlorn and debilitated.

By October of 1918, the United States began to feel influenza’s wrath. That winter, officials noted to the public how the ailment “spreads rapidly where people are crowded together in railway trains, in theatres and places of amusement, in stores and factories and schools.” By reporting this information in the New York Times, there was recognition that the media provided a powerful tool to put public health into practice. Despite these efforts, for most Americans, influenza was truly indiscernible, misunderstood, irrevocably infectious, with little treatment for the frail. What was even more difficult is that the very spaces where people gathered—churches, mills, and restaurants—were where the virus continued to endure and transmit itself.

Even with quarantine and public health measures, the flu took on a life of its own. Most insidious of all, the virus presented itself such that its early stages could easily fall under the banner of less serious, yearly, conventional flu. The sneeze or cough was at first little more than an inconvenience, a subtle but incessant probe through one’s chest. Nevertheless, the world war continued on while the microbe flourished, far more deadly than any weapon employed by humankind. Although there is little reliable data on how many people were infected with the flu virus between 1918 and 1919, researchers estimate that approximately 500,000 people in the United States, and an estimated 40 million in the world, died from the pandemic. Influenza wasn’t a new disease; instead, the conditions of the early twentieth century, which put a higher number of people in close proximity, increased the opportunities for the flu’s circulation and unsentimental wrath.

*

Early versions of influenza surfaced many times during human history. In some cases, medical philosophers classified the disease according to the plagues of their time, and in other circumstances, it became a metaphor for war. During his lifetime, the ancient Greek philosopher Hippocrates compiled a catalog of infections in his Corpus Hippocraticum, which provided insight into the etymology and progression of various diseases. Hippocrates writes of the “Cough of Perinthus,” a fifth century B.C. epidemic that swamped a Greek seaside town on the Sea of Marmara, afflicting the upper respiratory tract in what is thought to be the first influenza epidemic in human history.

But flu-like symptoms had pre-modern roots and these diseases’ social and linguistic imprint carried on throughout the early modern period. During the sixteenth century, Italian physicians identified a condition they called influenza di freddo, meaning “the influence of the cold,” a condition they later described as a chilling effect on the body. While the record is not clear on whether this pre-modern definition mapped onto the medical description during the classical period, influenza terrorized humankind frequently throughout the subsequent century.

The earliest account of an influenza epidemic in the modern era appeared in Britain in 1803. Dr. Richard Pearson, a London-based physician who conducted observations of the epidemic during the initial phase, affirmed: “The Influenza, as it appeared in 1803, is precisely the same disease which has extended itself at different periods for near a thousand years.” By 1831, a lethal strain swept across Europe with successive waves in 1833, 1837, 1847, and 1889. The recurrence of these outbreaks suggests that influenza slipped through the ever-growing cracks of society—ongoing class war, mounting anti-colonial strife, and concurrent disease crises, such as cholera. Prior to the development of germ theory, the waves were perceived to be random acts of God, but with time, and in some cases, people began to ascribe disease to specific places and people.

As Patrick Berche recounts in his article “The Enigma of the 1889 Russian Flu Pandemic,” the 1889–1892 flu outbreak was “the first pandemic of the industrial era for which statistics have been collected,” an indication that governments wanted to account more thoroughly for emergent infection and mass death. When the 1889 outbreak initially struck the Russian Empire, even including Tsar Alexander among its victims, many aspects of Russian life came to a halt—with factories, ports, and schools temporarily closed. Eventually, the disease spread from Russia to Western Europe, arising in Berlin, Copenhagen, and Paris.

In 1891, the northern English newspaper Yorkshire Evening Post reported: “In some cases there are three, four, and five sufferers in one house. Nearly all the members of the medical profession are actively engaged day and night in visiting, consulting and dispensing, and occasionally their surgeries are besieged by persons seeking advice and waiting for medicine for patients.” As physicians worked in these hospitals, they faced many obstacles—patients who cried over abdominal pain or children confused by their lethargic state. Although it was not as destructive as the 1918–1919 flu outbreak, between 1889 and 1894, the flu killed nearly 100,000 British people. The trouble with viruses before the twentieth century is that they had invasive tendencies, startlingly brutal in causing harm.

In the midst of massive uncertainty and mortality, imaginations run wild. One rumor blamed a novel technology—electric lights—for the contagion. At times, even early media was an outlet for false information. On January 31, 1890, the New York Herald ran an article suggesting that illumination from railway cars and steamship cabins was somehow responsible for a global influenza outbreak, noting, after all, “the disease has raged chiefly in towns where the electric light is in common use.” The article also noted that the disease “attacked telegraph employees.” Like many statements that lacked evidence, the tale played on people’s fear that innovation, leaps apart from and beyond tradition, could be the source of bodily harm. Beyond that, the economic depression of the 1890s, juxtaposed with growing discontent with authority, cast doubt on the general state of society at the end of the nineteenth century. The world stood in shock as a disconcerting wave of war and disease swept across even the healthiest people in European society.

At the outset of World War One, influenza had a different life. Thousands of soldiers who served in the trenches in the Rhineland or resided in barracks in Eastern Europe contracted influenza and were hospitalized. Sore throats, headaches, and fevers joined in as fighters suffered from ghastly wounds incurred during the battle. Unlike bullets, the flu did not just attack flesh; it unsettled the mind because of its overwhelming power over the body; the cold sweats rippled on the skin’s surface as strength quietly receded below. Doctors monitored, treated, and theorized about the life cycle of influenza while also contending with a government that wanted nothing more than to deflect blame for disease run amok.

In societies where fear could be spread through text, governments counteracted by shaping the flu narrative. Under the 1914 Defence of the Realm Act, British media were prohibited from printing or spreading information that might “cause disaffection or alarm.” On the surface, the legislation was sensible by trying to minimize collective stress. But in reality, it unlatched the doors for censorship, particularly about the origins of the outbreak. So long as Britain was not considered the origin of the flu, publications were permitted to write as they wished. During the early months of the 1918 influenza outbreak, the British media—similar to other Western media outlets—referred to the disease as the “Spanish flu,” a denotation that bears resemblance to the 1889 “Russian Flu” outbreak.

This work to otherize the malady—as a foreign invasion—neither reduced anxiety nor prevented the illness; instead, it perpetuated a message that the flu was an uninvited guest overstaying its welcome (and perhaps of less concern to England’s domestic population). Nevertheless, in Britain, similar to the United States, soldiers disproportionately fell ill to influenza, which meant that the population associated the contagion with militarization. A 1919 piece in the Manchester Evening News reveals an unfortunate and mislaid hope that human bloodshed and conquest could defeat the virus.

The end of the war did not end the Spanish flu. As the death rate soared, the joyful crowds gathered to welcome the Armistice in Albert Square, Manchester, unwittingly inviting the Spanish Lady to join them. The killer virus remained active well into 1919.

Even when the war ceased, influenza’s reign did not wane. The global impact and power of 1918 was unrelenting and exposed a fester in the public health practices in even the world’s mightiest and wealthiest nation-state of the time. In 1918, well before the establishment of the National Health Service, Britain proved ill-equipped to maintain its people’s health in a time of catastrophe. The outbreak caused the government to shift its policy from one of relative inactivity to a suite of diverse tactics, led by a patchwork of charity organizations and government initiatives.

British doctors implored radio programs and film productions to warn people about the dangers of the influenza. One of the most enticing British films campaigning for public health was an eighteen-minute silent production, Dr. Wise on Influenza. The video begins with a grainy shot of an elderly man standing in front of a microscope. Like many broadside films of the time, the moving pictures were interlaid with a message. Throughout the program, we see people sick with the flu, sneezing on others, taking public transportation, and unable to get out of bed. The flu takes a toll on their bodies, but as we see, the virus also spreads throughout the city.

But unlike an apocalyptic film where the viewer develops affinity for the character, the cinematic program provides directives. In one card, Dr. Wise informs the audience that “All infectious diseases, such as influenza, are caused by the invasion of microbes,” and in another he recommends that a flu patient treat himself by, “gargling his throat and douching [sic] the nose with potassium permanganate and salt.” Public health messages such as these were modestly funded by the Local Government Board in Britain, offering a visual aid on how to behave.

The flu was not only a phenomenon of mass contagion, which rumbled through entire communities; it was also a private battle that people felt in their beds.

Regardless, societies would need more will and better coordination to tackle the flu. By 1919, the city of London centralized its public health system, partially through the establishment of the Ministry of Health, by expanding regular street cleaning and waste removal services. Initially concerned with child and maternal health, small as they may seem, these measures played a crucial role in growing the arsenal of government-funded initiatives to secure health and confidence for everyone. By the end of the decade, officials were reluctant to introduce quarantine restrictions on buses and trams for fear of damaging morale. Still, they took some time to conduct this collection for influenza.

We take for granted today the precision—perceived or otherwise—granted by modern record-keeping and statistics for most of the West. We can record a birth through a certificate, or confirm a cause of death through an autopsy. But these mechanisms did not always hold in early 1919—especially for the working poor.

In November 1918, the Times reported a salacious article, “Triple murder and suicide,” suggesting that murder and suicide were linked to the influenza outbreak. Aiming to enliven the dull rhythm of life, the paper veered slightly from the truth. That fall, Leonard Sitch, an avid baker in Suffolk, England, had a breakdown, stabbed his wife and two children, and eventually hanged himself. Some of his neighbors were in disbelief, citing that he was respectable, while others told reporters that his mental health was attributed to the aftershock of having the flu. Although some people were skeptical about the relationship between influenza and psychosis, at the time, some scientists believed there might be an association.

During the first part of the 1918 pandemic, doctors occasionally cited psychosis when reporting on the pandemic. In 1919, the British physician Dr. George Henry Savage believed that influenza deteriorated the nervous system, which could subsequently “originate any form of insanity.” What he argued was that when people were bedridden, dark-eyed from the flu, time ceased. Savage was not alone in his thinking. Karl A. Menninger, an American physician, conducted a study in 1919 at the Boston Psychiatric Hospital and surmised a link between influenza and mental health disorders such as dementia and delirium. At a moment when physicians were trying to figure out why and how people were getting sick, they wanted to find a bridge between the predilections of the body and mind.

Mental illness—as lived by the people who suffer from anxiety and depression—is so distressing precisely because the person can become, as author Rachel Aviv notes, a “stranger to themselves.” Derangement, depression, and suicide did coincide, the data says, with influenza outbreaks, but they were most likely a consequence of the social unease and material strain that existed in the early twentieth century. The lingering ghosts of world war, profound class division, and unaddressed traumas surely reinforced alienation and more grave psychiatric issues.

Disease response was fragmented and complicated. In 1921, the Times noted that London was still haunted by the pandemic, to the point that “our minds [were] surfeited with the horrors of war,” which, in turn, resulted in even more carnage because of the “catastrophe” of the flu. Society was under immense pressure not only to attend to the dead but to find small ways to secure some agency for the living. On November 6, 1918, in southeast London, one superintendent requested that the local government provide him with twelve gravediggers because he had a backlog of corpses to bury.

Not every public health measure was morbid. Some found solace in even the smallest measures of control over a spiraling environment; residents in London’s Hackney neighborhood, for example, were advised not only to isolate themselves in their beds if they had flu symptoms but also to rinse their mouths with salt and potato. In addition, some of the most controversial public health tools were enforced quarantine and surveillance. Public health methods were rooted in individual responsibility, even if they included practices that today would seem far-flung from germ theory; isolating oneself in bed, and engaging in homeopathy, was part of staving off disease. For industrial workers, whose wage was dependent on showing up to the factory, this was not always possible.

Contrary to popular thought, the 1918 flu would claim more lives than the bubonic plague. In Britain alone, that death toll was over 200,000. The inescapability of infection meant that people sought care wherever they could find it. The bed featured as a place where flu patients—whether in a public military camp or their private homes—found refuge. People’s experience with the flu did not always look the same. For soldiers on active battle duty, most of whom were living in close quarters, social distancing was nearly impossible. But a section of the creative workers, many of whom came from the upper class, had more autonomy on how their home situation was structured. The flu was not only a phenomenon of mass contagion, which rumbled through entire communities; it was also a private battle that people felt in their beds.

__________________________________

From A History of the World in Six Plagues: How Contagion, Class, and Captivity Shaped Us, from Cholera to COVID-19 by Edna Bonhomme. Copyright © 2025. Available from Atria/One Signal Publishers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.