In 1959, Norman Mailer—between novels at the time—published a book called Advertisements for Myself. Even for Mailer, it was an unusual book—part compendium of unpublished short fiction, part clearing house for published short fiction, part a series of “Advertisements,” in which the writer, according to his own “Note to the Reader,” “surrounds all these writings with his present tastes, preferences, apologies, prides and occasional confessions.”

Article continues after advertisement

While it’s difficult, in 2025, to make much of a case for some of the fiction Mailer included (“The Time of Her Time,” basically a story about a woman’s very weirdly achieved orgasm) or even to see the nonfiction (“The White Negro,” “The Homosexual as Villain”) as having any but a historical interest, the Advertisements themselves stand as something sort of extraordinary, an unfiltered declaration of the kind of ambition novelists don’t normally trumpet these days.

The book is of particular interest to someone like me, publishing my sixth novel, and thinking a lot about how novelists used to pitch themselves in an age when the novel itself had a heightened cultural importance.

What drew me back to Mailer’s book after nearly fifty years was my memory of one long section, titled “Fourth Advertisement for Myself: The Last Draft of THE DEER PARK.” It’s twenty pages long, and consists mostly of the narrative of what happened to Mailer after submitting what he considered a finished draft of his third novel to Rinehart & Co.

Though the publisher had contracted for the novel, they found a very sneaky way of rejecting it (largely due to worries about the sexual content), which led to Mailer’s subsequent rejection by seven different publishers before landing at G.P. Putnam’s. By then something had happened to Mailer. Putnam was ready to publish the book, had it in galleys, but Mailer had decided he no longer liked his own prose.

The book is of particular interest to someone like me, publishing my sixth novel, and thinking a lot about how novelists used to pitch themselves in an age when the novel itself had a heightened cultural importance.

He had created a narrator who had been “cool enough and hard enough to work his way up from an orphan asylum,” but had somehow allowed him “to write in a style which at best sounded like Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby.” In detailing the summer’s worth of work he did to change that narrator’s voice—which amounted to a plunge into drugs and sleeplessness and a confrontation with the writer’s own shaky psyche—Mailer manages to commemorate something lost to the great majority of novelists writing and publishing today: a sense of the importance of what he was doing.

His was a world in which novelists waited to be judged by a venerable, harsh-but-dependable bank of critics. A world in which a writer’s own prose revealed to him a sense of his own personal strength and weakness.

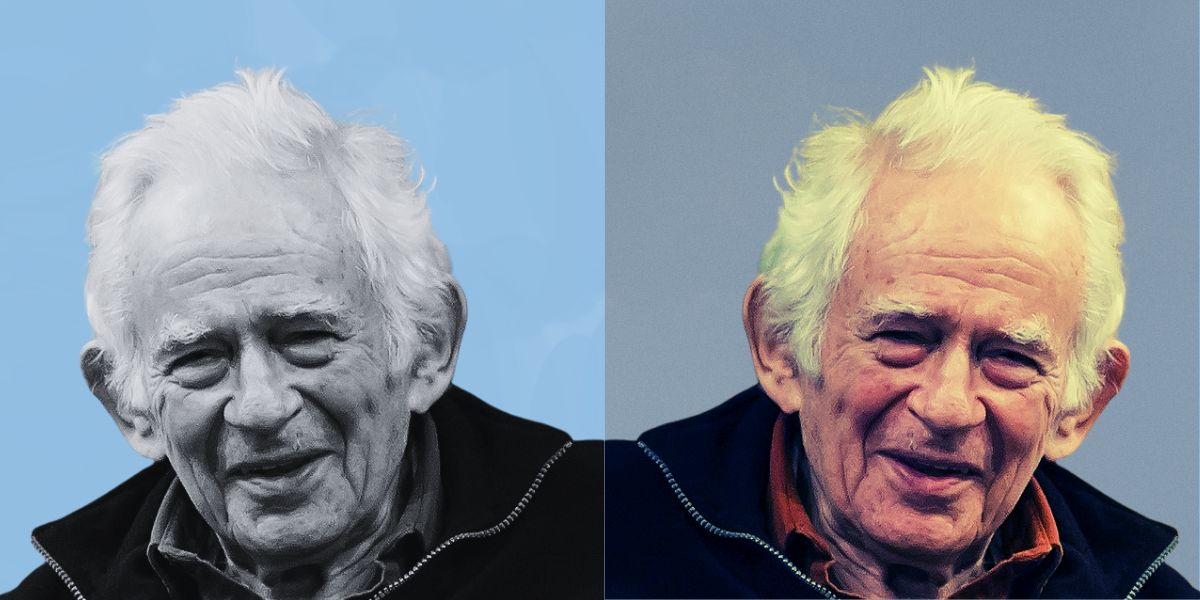

My own reading of Mailer goes back to high school, when I read his novel An American Dream, largely for the sex in it. I moved on to The Naked and the Dead, then read virtually everything the man published up through 1984’s Tough Guys Don’t Dance, at which point the sexual stuff I had initially been drawn to began to seem entirely too retro, and entirely too much. But fandom seems beside the point when a novelist writes as brutally about his own process as Mailer does here.

Mailer being Mailer, there’s a good deal of fighterly metaphor that needs to be discarded (“the life of my talent depended on fighting a little more,” “I needed the energy of new success, I needed blood.” ) What compels more deeply is the vulnerability of waiting for what the reviews are going to say, after publishing a second novel (Barbary Shore) that had not been treated kindly.

“With the reserves I was throwing into the work, I no longer knew if I was ready to take another beating.” Mailer is at his best writing about the actual effect that follows taking such a “beating”: “I knew a time could come when I would no longer be my own man, that I might lose what I had liked to think was the incorruptible center of my own strength.”

However pompous that may come off to contemporary readers, Mailer is getting at something. Writing in a way that will protect oneself, to keep from taking a beating, Mailer warns, is to risk something enormous.

It all reads as entirely existential, and the wonder, for a writer publishing in 2025, is to consider how deeply public it all once was. Mailer writes as if he’s waiting to face a gang of executioners, all of whose names he seems to know.

He knows without doubt that once the novel comes out, he’ll face the big guns at Time and Newsweek, Harper’s and The Atlantic, The New York Times, of course, but also the Herald Tribune, Commentary, Saturday Review, The New Yorker. What existed for Mailer—the certainty of the big public judgment—has devolved in 2025 to the simple plea coming from the majority of us: please notice me.

One of the things that rereading Advertisements for Myself has made me wonder, however, or perhaps simply to question, is how much we- novelists in the early twenty-first century—might be in some part responsible for our diminishment within the culture. Has our curtailed ambition—our refusal to take after writers like Norman Mailer—landed us in a place where we simply don’t matter as much?

Regarding this question, the writer Charles Baxter wrote to me: “Novelists like Mailer who thought they commanded the big bow wow orchestra were supplanted by novelists and short story writers who ended up writing chamber music to a smaller audience.”

We made that choice, I believe, because we took a hard look at the world of books that had preceded us, particularly (those of us who are male) at the big brawny post World War II guys and realized that Chekhov and William Maxwell had more staying power. We adjusted our instruments, and our ambition. But that doesn’t mean one can’t still read Mailer without a strong hint of envy for how much the struggle of writing a novel used to matter.

But then, maybe there’s a way that Mailer’s experience is still getting replicated, albeit in a different form. While Mailer waited for a gang of established critics to mow him down, one waits, today, for a very different set of critics, those less established but still powerful voices on the internet waiting to give one a “beating” for some of the choices we make.

The new novel I am publishing, Remember This, a novel with a wide-ranging canvass that includes the art market, the career of an Alice Neel-like artist, and the contemporary theater, also includes the travails of a largely heterosexual seventy-year-old man who travels to Haiti on a do-gooder mission, and proceeds to fall in love with an eighteen-year-old Haitian boy.

Though no sex ever occurs between the two, my early readers warned me about the quicksand I might be stepping into. The words “groomer,” “sexual tourist,” “predator” were bandied about.

The warning those readers were giving me was a double one. First, watch out for the way your own excesses—the flagrant manner with which you’re dealing with tricky material- might be off-putting to your potential readers. But watch out, too, for what might happen to you, upon publication, simply for entering such delicate territory.

They were right, of course, in the first part of that warning. Their voices convinced me to pull back from certain excesses, unnecessary ones.

But I knew that the second part of the warning was one I had to push past. The choice I’d made—to deal honestly with aging male desire—was one I had to stick with. The integrity of the novel depended on my not backing down from it. If that choice was to open me up to internet invective, so be it.

One writes what one has to write. One goes there. Then one takes the beating, in whatever form it takes.

And here’s where I’m forced to join hands, even a bit reluctantly, with Norman Mailer. Particularly with his articulation of what gets affected when one begins to back down from a dangerous challenge: the risk to “the incorruptible center of my strength” begins to seem less a self-important articulation than something utterly real.

One writes what one has to write. One goes there. Then one takes the beating, in whatever form it takes. One can learn—can go on learning, even at an advanced age—from the recorded struggles even of a writer of whom one has long ago ceased being a fan.

______________________________

Remember This by Anthony Giardina is available via FSG.