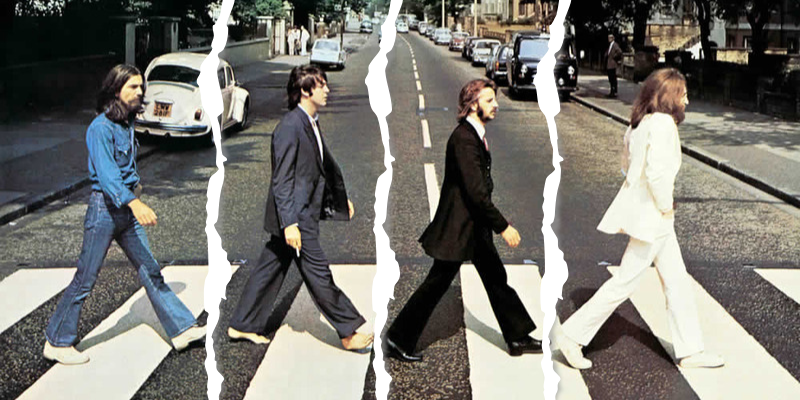

“Looking back on it, we did used to say, it’s like a divorce,” Paul McCartney reflected on the Beatles’ breakup, now a marathon heading into its fifth year. “It really was like that, but four fellas trying to divorce instead of a man and a woman. And then you get four sets of lawyers instead of just two. All of that kind of stuff was not making life easy at all.” At the moment, the lawyers were not the problem.

Article continues after advertisement

As Paul, Linda and their three daughters—Heather (11), Mary (4), and Stella (2)—were enjoying some downtime at High Park in Campbeltown between recording sessions in Stockport, the attorneys representing each of the former Beatles convened in New York on Monday, February 11, 1974—the tenth anniversary of the Beatles’ American debut concert in Washington, D.C.—to hammer out an agreement dissolving the Beatles’ partnership.

This had been Paul’s goal since early 1970, shortly after John Lennon announced to his bandmates that he was leaving the group. It was John, in fact, who first used the word divorce, likening his split from the Beatles—and the liberation he felt in declaring it—to his divorce from his first wife, Cynthia.

The holdout was John, who had dangled the prospect of signing such an agreement before Paul several times since 1971 but always reneged.

McCartney had not wanted to divorce the Beatles. He wanted to divorce Allen Klein, the brash New York manager whom John brought in to manage the Beatles and their company, Apple, which was losing money alarmingly by early 1969. Lennon’s enthusiasm for Klein won over George Harrison and Ringo Starr, but Paul resisted, arguing that Klein’s reputation in the music world was unsavory. The Rolling Stones, who had brought Klein to Lennon’s attention, subsequently warned the Beatles that he was bad news: Klein had negotiated the Stones an improved contract with Decca Records while quietly buying their master tapes and publishing (through 1971) behind their backs. Paul feared that he could walk off with everything the Beatles had built, as well.

Nevertheless, when Paul refused to sign Klein’s management agreement, the others overruled him, breaking the Beatles’ longstanding rule that all major decisions be unanimous.

The idea of Klein being considered his manager, not to mention his taking a cut of the royalties on the Beatles catalog and his own albums, was galling to Paul, but the only way to get Klein out of his life was to extricate himself from Apple, and the only way to do that was to dissolve the partnership agreement that the Beatles signed in 1967. Unable to persuade the others to let him out of that agreement, Paul reluctantly followed the advice of his lawyers, Lee and John Eastman (who were also his in-laws, Linda’s father and brother), and took them to court to force the dissolution of the partnership.

He took a publicity hit when he sued the other Beatles and Apple, but he prevailed. Yet, four years later, the battle still was not over. Because the Beatles did business as Apple, not as John, Paul, George and Ringo, their recording contract was between EMI Records and Apple, and according to that contract, all royalties for Beatles and solo recordings were paid to Apple. A receiver had been appointed to sort out Apple’s byzantine finances, so that the money could be split. But finally splitting the company—and distributing those royalties—required a dissolution agreement signed by all four former Beatles.

The holdout was John, who had dangled the prospect of signing such an agreement before Paul several times since 1971 but always reneged. This was a significant inconvenience to Paul. In the summer of 1971, he had formed a new band, Wings, and he was paying his bandmates a weekly salary, underwriting touring and recording expenses, and running management offices (McCartney Productions Ltd., or MPL) in both London and New York to oversee it all. Yet his royalties for the last few Beatles releases, as well as his five post-Beatles albums (two solo, three with Wings), were frozen in Apple’s bank accounts.

Now, at long last, the four sets of lawyers were meeting, and the end was in sight.

Much had changed over the past year. For one thing, Klein was no longer in the picture. When his contract expired in March 1973, the other Beatles opted not to renew it. “Let’s say that possibly Paul’s suspicions were right,” John commented at the time.

More importantly, the personal relationships between the former Fabs were stronger than they had been since 1969. “Yeah, I miss Paul a lot,” John told NME in mid-January 1974. “Course I’d like to see him again. He’s an old friend, isn’t he?” Elsewhere in the same issue, John was quoted saying, “I think anything is possible now, and if it happens, I’m sure we’ll all do something wonderful.”

All four were pursuing solo careers with notable success, if not quite at the level of (near) infallibility that they had enjoyed as the Beatles. Talk of potential collaborations, once angrily swatted away, were now offered as possibilities, however vague. In the February 16, 1974, edition of Melody Maker, Chris Charlesworth reported from New York that a joint statement from the former Beatles would be released in the near future, a tip that Charlesworth interpreted to mean the announcement of a new Beatles album.

Lee Eastman’s first reports from New York were encouraging. The talks were productive, and the attorneys would press on, hoping to have an agreement by the end of the week. But there were complications. Klein was suing Apple for what he claimed were unpaid fees, and Paul’s position was that since he had warned the others against signing with Klein, he should not be liable in the event that Klein prevailed. He therefore insisted that the other three indemnify him against that possibility.

Another issue was that the Beatles’ individual homes were purchased through Apple and were technically among the company’s assets—something that had to be considered when splitting those assets among the four musicians.

Yet another sticking point was that John had been charging his New York living expenses and the cost of his film projects with Yoko Ono to Apple, and by the end of 1973, those expenses totaled about $2 million (£860,000), money that Paul, George and Ringo wanted reimbursed to the company. And there was the not inconsiderable matter of how to deal with recording expenses that the individual Beatles, as well as Yoko, had charged to Apple.

When Lee Eastman telephoned again on Friday, February 15, Paul was expecting to hear that after five days of negotiation, they had a contract that satisfied everyone, and that his freedom was at hand.

Instead, Eastman delivered the stunning news that with negotiations at an advanced stage, Lennon’s attorney piped up with a last-minute demand from his client: Lennon would not sign unless he was guaranteed an extra £1 million ($2.3 million). It was a demand too outrageous to discuss, and the negotiations ended abruptly.

“I asked him why he’d actually wanted that million,” Paul recalled, “and he said, ‘I just wanted cards to play with.’ It’s absolutely standard business practice. He wanted a couple of jacks to up your pair of nines.”

In calmer moments, Paul recognized that the negotiations were a complex dance, and that all four former Beatles had priorities that were no longer in sync. Financially, there was a lot at stake for Paul, too. While the critics were often divided over his post-Beatles output, McCartney’s record sales were healthy. In America alone he had sold over four million LPs, the royalties for which were currently sitting in Apple’s bank accounts.

“I mean, there were many stumbling blocks. And just to keep the record straight, it wasn’t always [John]. I mean, obviously they accused my side of doing plenty of stumbling too.”

But John’s demand was more than legal poker play. In purely practical terms, Lennon forced the delay to be sure that neither he nor his lawyers had overlooked any details—whether, for example, the tax ramifications of the settlement would be more severe for him, as a British subject resident in the United States, than for the others.

On a purely emotional level, Lennon was also conflicted about the finality the dissolution agreement represented. Granted, he had occasioned the split and he had demonstrably moved on, musically and personally; but he was also the band’s founder, and despite his public assertion that “it’s only a rock group that split up, it’s nothing important,” he saw the Beatles as his own creation.

“Everybody changes,” said May Pang, Lennon’s companion at the time. “With John, things changed on a daily basis. Even though they had to break up to get to the next level in their musical careers, at the same time, he started this band that changed the world. It wasn’t just a band that said, ‘Oh, we made six albums.’ It changed pop culture. It changed how we live and how we dress. And he knew that.”

To the other lawyers, Lennon’s demand was little more than a stunt, something to be expected from the most mercurial of the Beatles. So in conveying the news to Paul, Eastman also offered his belief that Lennon’s demand was just a hiccup in the proceedings and would soon be sorted.

But Paul was livid. Seemingly unconcerned about leaving Linda and the girls stranded at High Park without a car in the dead of winter, he stormed out of the farmhouse, hopped into “Helen Wheels,” his Land Rover, and took the coastal road out of Scotland and toward Gayton, the Merseyside village where he had bought his father a house, called Rembrandt.

To the other lawyers, Lennon’s demand was little more than a stunt, something to be expected from the most mercurial of the Beatles.

Linda contemplated the prospect of staying in Scotland and leaving space for Paul to cool off. But after a few hours, she decided to head for Rembrandt and ordered two cabs to accommodate a traveling party that included Linda and the girls, plus four dogs, each larger than the two youngest girls. Reggie McManus, the owner of the Campbeltown cab company, was taken aback when Linda requested two cars for the nearly 360-mile trip to Gayton but agreed, provided that Linda didn’t mind making it an overnight journey.

McManus and another driver, Bob Gibson, collected Linda, the girls and their small menagerie at High Park at 12:20 a.m., and delivered them to Rembrandt on Saturday morning at around 10. The marathon journey racked up a fare of £70 ($170), which Linda paid from a roll of banknotes. To Linda’s surprise, when she arrived in Gayton, Paul was having a cheerful breakfast with his father, his rage diffused by the head-clearing drive south.

Linda was used to Paul’s temper, a characteristic that he had always carefully shielded from public view, projecting instead an enthusiastic Cute Beatle veneer. She and Paul quickly put his fit of pique behind them, and the next day, when Paul sat for a lengthy interview with the New York Daily News’s Sunday magazine section—a chat that began in early afternoon and continued that evening after a break for some horse riding—his paeans to marriage and family were laid on thick. “Linda and I know that marriage is old-fashioned,” Paul told his interviewer, Karin von Faber, “and we know the contract is just a piece of paper. It’s up to the people what they make out of that piece of paper. I had my wild life. I really had a wild time, especially when we toured America in 1964. But I told Linda everything about that and all the rest. I have no secrets from Linda. I had my time, in my time. But I am much happier now. This new life means more to me.

“No matter how much money Linda and I may have, it means nothing to us without this kind of happiness. It’s a great pleasure—and a tough job—to raise children. With female children, you want to try to teach them early to understand men as much as possible. Men and women are so totally different they spend a good part of their life trying to get closer to each other. Of course, they rarely get close enough. That’s the problem. They should start early. I don’t mean sex. I mean understanding, communicating, like the beautiful thing I have with this blond lady.”

But Paul’s anger about the inconclusive legal negotiations was not far from the surface, and he wanted to be sure his side was heard, and in perspective.

“All of us realized that this great thing we’d been part of was no longer to be,” Paul told von Faber. “I think we’ve all accepted it as a fact since that day in the Apple office in London when John told us—‘I’m leaving the group, I want a divorce.’

“Linda and I aren’t rich people because so much of our money has gone into Apple. That’s a disaster. Our former manager, Allen Klein, did some pretty strange things with the millions we made. Linda’s dad is our attorney, and we’ve sued Apple, and we may get rid of the whole mess and get a settlement in the next few weeks. I sure hope I can clear it up. You know, the other Beatles didn’t believe me when I said Klein wasn’t the right man to handle our affairs. I took a lot of abuse from John, George and Ringo for my position. But it turned out I was right in the first place.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from The McCartney Legacy: Volume 2: 1974-80 by Allan Kozinn and Adrian Sinclair. Copyright © 2024. Available from Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.