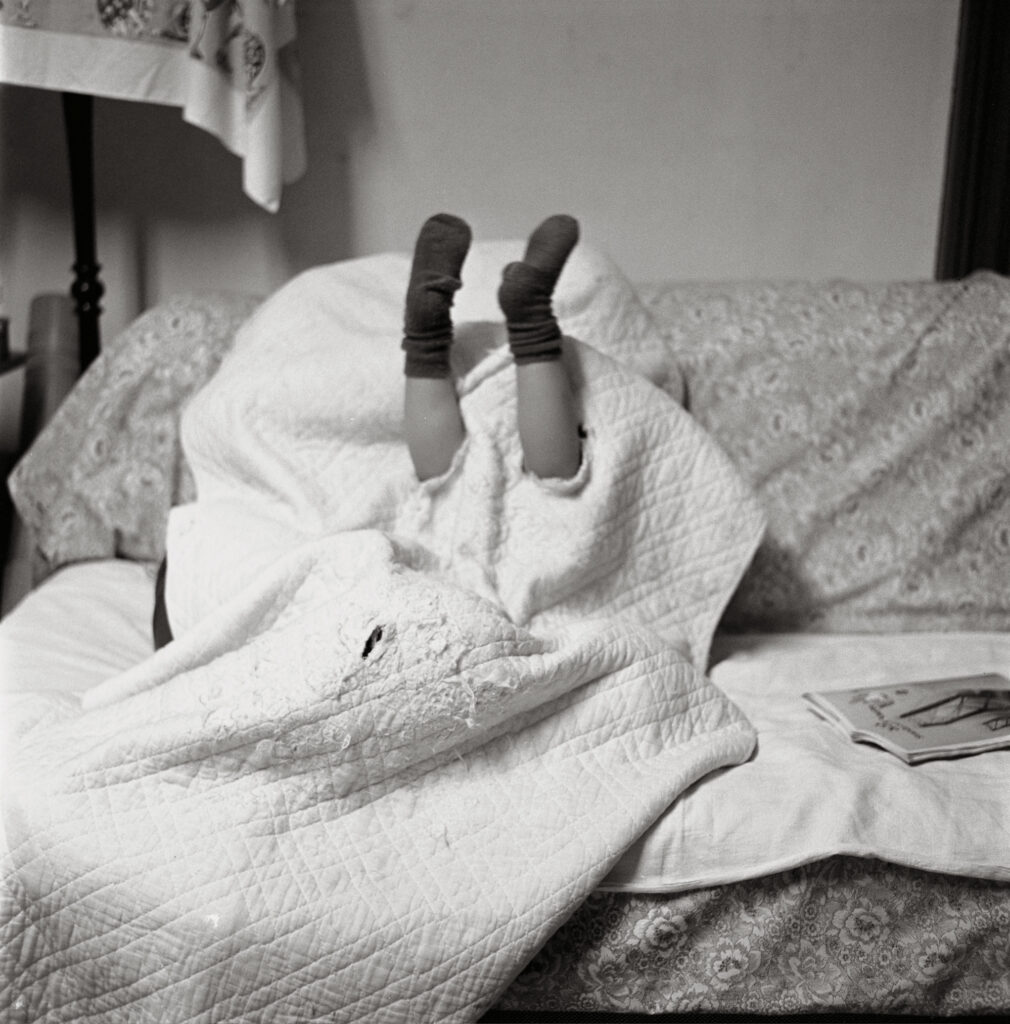

Featured image: Kawauchi Rinko, Untitled, 2004; from the series the eyes, the ears. Courtesy the artist and Aperture.

Article continues after advertisement

To be a woman in Japan is to live with constant conflict. In a country where attitudes toward gender remain extremely conservative, simply being a woman exposes one to many forms of prejudice and discrimination. Japan ranks 125th out of 146 countries in the Global Gender Gap Index as of 2023, and it continues to languish at the bottom. This disparity is reflected in women’s limited opportunities for success in the world of photography.

To note a few examples: I was once “advised” by a famous male photographer, who also happened to be the principal of a photography school, to marry a rich man if I wanted to become a photographer. This was in 1995, approximately ten years after the enactment of the Equal Employment Opportunity Law, which aimed to provide equal opportunities and treatment in the workplace regardless of gender and opened doors for more women. Between 1997 and 1999, the forty-volume book series Nihon no shashinka (Japanese photographer) was published by Iwanami Shoten. Widely regarded as the primary reference on the history of Japanese photography, it focused only on male photographers. Moreover, in the first twenty-five years of the Kimura Ihei Award, one of Japan’s most prestigious photography awards, only three recipients were women, until 2000 when Nagashima Yurie, Ninagawa Mika, and Hiromix were asked to share the award.

We must remember that these are the kinds of facts and experiences that have shaped the women in this book. They are survivors. At the same time, their exclusion from mainstream photography is precisely what has allowed them to observe things from a distance. Ironically, this exclusion may have been a result of their experimental approaches, which challenge the established values of photography and the nature of the medium itself.

For better or worse, pioneering women artists such as Yamazawa Eiko, Ishiuchi Miyako, and Ishikawa Mao stubbornly forged their own paths alone, distinguishing themselves from the artistic trends of their time. That widespread recognition of their work has been so delayed can be explained only by the overwhelmingly homosocial, male-dominated world of Japanese photography in which they emerged, one that relegated women photographers to an inferior position. In Ishikawa’s case, this was further complicated by the political and historical relationships between Okinawa and Japan, and the legacies of the American occupation—as well as the social commentary inherent to her work on the topic.

Many women artists who started out as photographers also gradually expanded into other genres such as film, theater, and literature. Cross-genre work has become increasingly common worldwide since the 1970s, with artists—both men and women—drawing from multiple artistic fields and techniques. Yet the connection between the photography and art worlds in Japan has historically been tenuous, and the stark gender gap in both fields has made it difficult for artists who began their careers as photographers to be fully appreciated for their distinctive contributions.

*

Over the past decade, the world of photography has made a concerted effort to tend to critical gaps in its historiography. A significant emphasis has been placed on redressing the underrepresentation of women artists, resulting in a rich array of individual and collective exhibitions and publications worldwide. The excavation and recovery of women’s work serves as a testament to the liberating nature of self-representation and self-expression, and to the importance of photography as a medium to express and share one’s own story: to be heard and to be seen.

In the same spirit of restorative history, this project highlights the extraordinary work produced by Japanese women photographers from the nineteenth century to today, with a particular focus on their production from the 1950s onward. Since the 1970s, Japanese photography has become the subject of major books and international exhibitions, but recognition has primarily centered on male photographers such as Sugimoto Hiroshi, Moriyama Daidō, and Araki Nobuyoshi—arguably among the most well-known in the photo world outside Japan. Meanwhile, innumerable Japanese women photographers have played a key part in the medium’s development, from its introduction to Japan up to the present day. Unfortunately, their practices have remained largely underrepresented and underappreciated both abroad and within Japan. Through a wide-ranging selection of images and essays, this book offers a critical and celebratory counterpoint to what is known about Japanese photography. It seeks to challenge and complement historical precedents and the established canon.

__________________________________

From I’m So Happy You Are Here: Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to Now, edited by Pauline Vermare, Lesley A. Martin and Takeuchi Mariko. Copyright © 2024. Available from Aperture.