When Zora Neale Hurston died in January 1960, much of her belongings, including a trunk holding her papers, were burned. But in a series of fortuitous circumstances, a neighbor and friend salvaged some of Hurston’s papers, which were later turned over to the University of Florida in Gainesville.

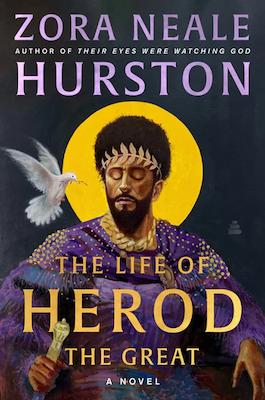

Among Hurston’s salvaged papers were the pages of her fictional account of The Life of Herod the Great, which Hurston was writing to correct the long-held belief that Herod was a villain responsible for “the slaughter of the innocents.” Rather than the evil king portrayed in much of literature, Hurston wanted readers to “be better acquainted with the real, the historical Herod, instead of the deliberately folklore Herod” and learn the historical patterns that established the western world as we know it.

Using Hurston’s papers, including excerpts from her letters, editor and scholar Deborah Plant—who previously edited Hurston’s Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo—has brought this novel to life. I spoke with Plant about the editing process for a salvaged novel, working with partially destroyed text, and what a novel about the first-century BCE Judea teaches us about contemporary life.

Donna Hemans: The Life of Herod the Great has an interesting publication history, including being salvaged from a fire. Tell us about how it was salvaged?

Deborah Plant: Hurston was living in Fort Pierce, Florida, when she became ill, but before becoming ill, she was still writing her manuscript on Herod the Great. She was actively revising her drafts, submitting letters, and various drafts to potential publishers. She hadn’t been successful with getting any reception, but she kept refining the work nonetheless. And by 1959, when she had a stroke, she couldn’t continue the work with the manuscript.

She eventually passed and all the material that was in the home where she was living before she died was being taken out of the house because they were clearing it for the next tenant. And the protocol was that stuff which could be burned would be burned.

And part of what those who were clearing the house were burning were contents from a trunk, that she had kept her manuscripts in. And one of her friends, who was also a deputy sheriff, was driving by. He saw the fire and he immediately went to put the fire out, and managed to save some of the contents of the trunk. And so this is how we managed to still have Herod the Great.

DH: How did you become involved?

[One of her friends saw the fire and] managed to save some of the contents of the trunk. This is how we managed to have Herod the Great.

DB: Another friend of hers, Marjorie Silver, gathered those papers that were salvaged and deposited them with the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida. It’s available to scholars to examine and I am one of those scholars who was able to do that and have the grace and the blessing of the Zora Neale Hurston Trust to go ahead and prepare the manuscript for publication.

DH: So the family blessed the publication itself?

DP: Oh yes. I wrote a proposal like you would do for any book, whether it’s the book you want to edit or book you want to write yourself. In this case, you write a proposal not only for the potential publisher, but also for the trust, because they have oversight of the personal material. And I wrote more than one. But eventually the trust appreciated the last proposal, and they felt it was a proposal that would do justice to Hurston’s work and they gave me permission to go ahead with it.

DH: What’s the editorial process like for bringing a posthumous work to print?

DP: With this manuscript there was so much involved because it was pulled from a fire. Also, it was a draft that came to us unfinished, and I put quotations around unfinished, because we really don’t know what else we lost. We could have lost a version that was completed.

In terms of what we did have, we had to figure out how to prepare it, especially when, in some cases—for instance, with the preface and the introduction—there were several versions because she revised it. The narrative itself was in different phases. Some of it was in typescript. Parts were in long hand. Pulling all of it together took a lot of consideration and time. With the manuscript being copied by someone other than myself, that proved to be problematic, because the copying was improper in many instances. I wound up making a lot of copies by using my iPhone, which happened be a good thing. The iPhone copies were in color and actually allowed for more of the text to be seen, particularly on those pages that were singed.

DH: How did you handle missing text?

DP: I didn’t want to guess what she was saying, and I wanted to have enough context to make the best choice based on what else she was saying. With the copies that were done in color, I could see more of a word, more of a sentence, than I was able to see when it was in black and white.

And then I did background reading to learn as much as I could about the history to understand what she was up to. That allowed me to see where she was going in the manuscript, and how the chapters were connected, particularly when not everything was in typescript. Knowing that background helped me to understand how she was organizing the chapters. Then there was the question of what to do about those instances where I could not discern what was written, typed or in longhand, because something was missing, or because of the singed pages. And there were a lot of singed pages, whether on the top, bottom or the sides of pages.

That meant making sure I knew the narrative flow, and seeing where it would more easily transition in terms of what needed to be excised, because some of that had to be done too. And then figuring out how to be the editor without interfering with the writer, especially when the writer is not here to talk to you about what she wants to keep. But being a Hurston scholar all my life, I felt she would agree with the edits that were made because I know her work so well.

DH: So you had to do a certain amount of research or reading the historical material itself on Herod. Would this have gone differently if the book had not been based on a character represented in history?

DP: Even with a fictional work, I can imagine where hers might go, because I know her other work. She maintains the same kind of principles, the same kind of ideals. She’s always about justice, creativity, autonomy, and freedom. These are just hallmarks of who she was and who her characters were. This is what informs Moses, Man of the Mountain. This is what informs when Janie will speak her truth, when she will strike out for her own independence. The works that Hurston has already given us, whether they are fictional or ethnographic, would inform how I would read a manuscript.

DH: How beneficial was Hurston’s own notes and papers to bringing the book to publication?

Zora Neale Hurston’s always about justice, creativity, autonomy, and freedom.

DP: The ending was not in the salvaged papers but her letters, where she wrote about Herod and the latter part of his life, were instrumental in my being able to give the manuscript an ending she intended for it to have.

DH: You were also involved with Barracoon and bringing that book to publication posthumously. Was the editorial process similar?

DP: No. Barracoon was not in a fire and that work was pretty much intact. It was not unfinished. She wrote to Charlotte Mason, who was her patron, and said, “I have finished the manuscript draft of Barracoon and it’s ready for your eyes.” She was even sending it out to potential publishers. That work was actually complete, although there were some aspects that I had to address when I prepared it for publication. For instance, it was still a draft. She had notes on the back of pages that she wanted to insert in the manuscript, and I had to make sure that it was included.

Here again that work also was in typescript, which meant that I had to create a digital file. I was sent a current version of her manuscript, which I basically couldn’t use because the person who typed it was correcting the original. Because I know Hurston’s genius as an anthropologist and ethnographer, I knew that she would want that manuscript to maintain its integrity in terms of the dialect.

DH: Hurston’s preface includes a portion of the ancient Greek philosopher Polybius’s lecture to his disciples: “History may be a lantern of understanding held up to the present and the future.” What does The Life of Herod The Great say of our current lives?

DP: In the introduction, Hurston says history repeats itself. She points out that what was really prominent in terms of the turmoil of that period was this whole energy of the West’s efforts to dominate the east. There is this similar tension in the 21st century. It is the same struggle. Hurston said we must study history to see what this eternal struggle teaches us.

The answer is not in electing a strongman to rule and dominate us. It hasn’t worked in the past. It will never work. There will always be more war. They don’t bring peace. They don’t bring security. They don’t bring anything except their egos and ambitions. These so-called strongmen not only see themselves as saviors of a particular group or nation against the enemy, but they will also dominate the people that they represent.

It’s a rich history for us to look into and to see the same things that were done in Herod’s day. As James Baldwin would say, “history is not the past. History is the present.” I say history doesn’t repeat itself, it just continues. The only way that we can address that is to have a conscious awareness about our history and a committed intention to intervene in that history by looking at what has been done and the consequences of that. And look to see where we can do something different to create the kind of world that we want.

DH: The book is a continuation of Moses, Man of the Mountain. Can you talk about Hurston’s interest in biblical figures?

DP: Her father was a minister and her mother was a Sunday school teacher. She was kind of enthralled with the whole ceremony of church and what she called the poetry of her father. He would have the congregation spellbound. Hurston was mystified by it all, but at the same time curious and wanting to know more.

She talked in Dust Tracks on the Road about when she was punished as a child. She had to stay inside in one of the rooms and the only thing in there to read was the Bible. She was impressed with a lot of these biblical figures. She is a cultural anthropologist trying to understand humanity. And one of the ways you understand humanity is that you understand the worldview of a particular people. You come to understand spiritual ideals and that which grounds them spiritually. Doing all of that work—collecting folklores, stories, sermons—was part of her interest in the Bible and how we interpret the Bible, and gave her the capacity to distinguish between myth, legend, folklore, and history.

DH: Was this the last of her unpublished work? Should we expect anything more?

DP: I don’t know. The thing about the trunk that had her papers is we don’t know what papers were in there and which ones weren’t. Hurston traveled a lot. She had to leave her belongings with friends and places where she was staying. So I can’t give you a definitive answer. This is the only one I know about right now.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.