In August 2021 Sarah Rainsford flew back to Moscow from a reporting trip in Belarus. After a mysterious wait at passport control, a border guard approached. He produced a piece of paper. Reading with a “solemn air that was almost theatrical”, he intoned: “Sarah Elizabeth, you are banned from entering Russia as a threat to national security.”

Rainsford, the BBC’s Russia correspondent, was being expelled. After some hours at Sheremetyevo airport she was allowed to enter the country. Foreign ministry officials, however, soon made clear her reprieve was temporary. They told her she was being kicked out for good. It was, they said, a “mirror response” after the UK government refused to renew the journalist visa of a suspected Kremlin spy in London.

I read Goodbye to Russia – Rainsford’s excellent memoir of more than two decades reporting from Moscow – with a wry smile. In 2011 I was expelled in similar circumstances. In my case, a migration service guard pronounced: “For you, Russia is closed.” Like Rainsford, I was outraged. And then curious: what do these KGB-style episodes, mixing menace and dark comedy, say about what Russia has become? And its malign view of the world?

Prior to my kicking out, FSB goons broke into our Moscow family apartment and left behind a sex manual. The spies who entered Rainsford’s flat brought a different calling card – “a large unflushed deposit in each toilet”. These intimidation tactics are well known: a fuck you from a secret state. The BBC’s security team gave her a motion sensor to detect break-ins. It didn’t work; her husband used it to play Cuban salsa.

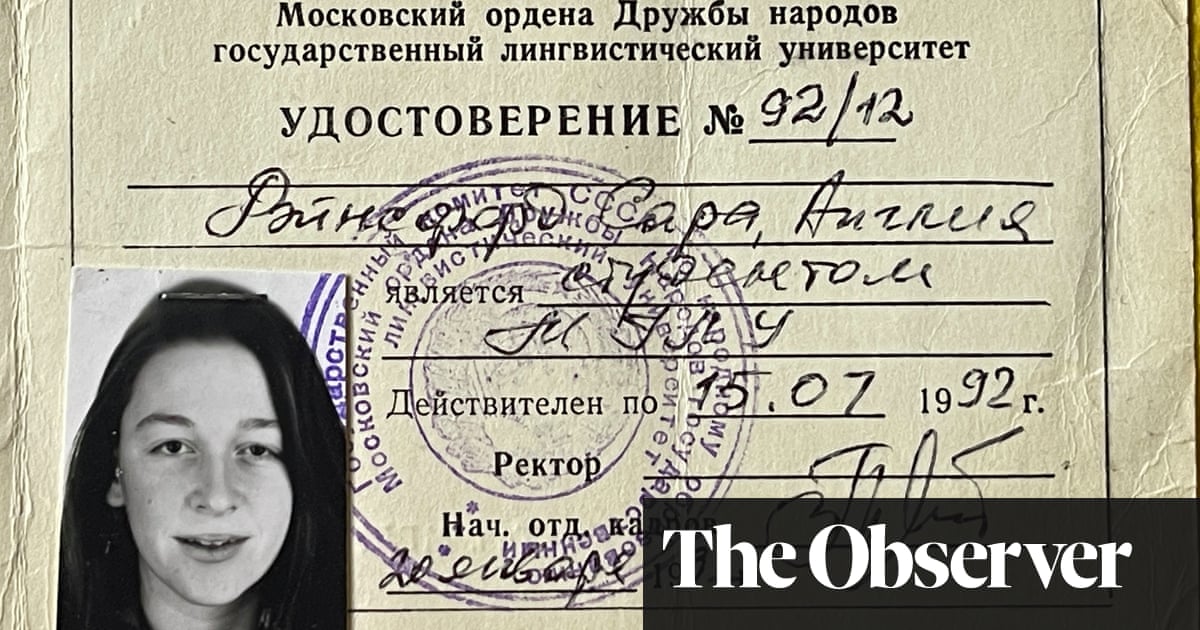

Rainsford’s expulsion meant an end to a long love affair with Russia that began in January 1992. A sixth-form teacher, Mr Criddle, kindled her interest in the language. Aged 18, she spent five months teaching English in Moscow. Her new home was “vast and still mysterious”, she writes; hungry people queued outside bare shops. President Boris Yeltsin had recently vanquished a coup by hardline communist plotters. Democracy, seemingly, had arrived.

So had organised crime. As a Russian student at Cambridge, she returned in 1994-1995 to study in St Petersburg. The city was a gangster paradise. One rising person was an ex-KGB officer, previously stationed in communist East Germany, and now deputy mayor: Vladimir Putin. Rainsford improved her conversational skills by getting a job in an Irish pub. “It’s possible I once pulled Putin a pint of Guinness. Or maybe a half,” she recalls.

after newsletter promotion

She did a stint as a telephonist on the royal yacht Britannia, when the Queen sailed in for a visit. By the time she returned to Moscow in 2000, as a BBC producer and reporter, Putin was president. Russia, she found, “provided an endless flow of stories”. She visited Chechnya, interviewed the liberal journalist Anna Politkovskaya and reported on the horrific Beslan school massacre, where 334 people – most of them children – were killed.

Putin was taking Russia backwards. It was becoming a full-blown authoritarian state with retro Soviet characteristics. Government critics and dissenters were ruthlessly persecuted and bumped off. Rainsford’s book begins with an account of the murder in 2015 of Boris Nemtsov, a charismatic politician and ex-deputy prime minister, gunned down next to the Kremlin. Politkovskaya and other independent journalists were killed as well.

Like her reporter predecessors, who in the 1970s covered the Soviet Jewish dissident movement, Rainsford spent time with brave Kremlin critics. One is Vladimir Kara-Murza, a Cambridge-educated historian, who was sentenced to 25 years for “treason” and who was freed last week in a prisoner swap. In 2019 she covered anti-government protests led by opposition leader Alexei Navalny. The Kremlin poisoned Navalny and banned his anti-corruption foundation; in February he died in a gulag.

Rainsford was in Ukraine when Putin launched his full-scale invasion and is now the BBC’s eastern Europe correspondent. “Any lingering nostalgia I had for Russia, and regret at being expelled, were extinguished in an instant,” she writes. As the first bombs fell, she describes Putin’s “snarling face” on TV and her “hands shaking”. “Reporting on the war was like covering no other conflict for me. My shame was mixed with revulsion,” she confesses.

Her book is a vivid and moving chronicle of Russia’s dysfunctional slide into mass murder. Rainsford tours Bucha, the Kyiv satellite town where young Russian soldiers tortured and executed civilians, and investigates the kidnapping of Ukrainian children. Her London flat is full of reminders of her life in Russia, including a collection of cheesy Putin mugs. She bins them. “For a long time I couldn’t bear to see any of the Russia stuff,” she says.

To what extent are ordinary Russians complicit in this? Ukrainians hold the entire nation responsible, including its intellectuals, many of whom have now fled. Rainsford disagrees. She identifies Kara-Murza and Navalny as patriots, damned as “traitors” by Putin’s shrill clique. She notes the “immense power of propaganda”, a way of controlling society. “It hangs in the air all around. It takes immense self-control not to breathe a little bit of it,” she reflects.

Rainsford has written a compelling study of Russia’s post-Soviet transformation into a fascist dictatorship. The BBC hangs on in Moscow, just. Other media organisations, including the Guardian, have gone, following the arrest of Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich. Last month a court jailed him for 16 years for “espionage”. He is now home following the biggest swap since the Cold War. The Kremlin no longer cares about its international image, if it ever did. The bright future Rainsford once imagined – of a Russia happy and free – is far away.

Luke Harding’s Mafia State: How One Reporter Became an Enemy of the Brutal New Russia is published by Guardian Faber.