You don’t necessarily think of William Boyd as an author of spy novels – not in the way you would think of John le Carré or Charles Cumming – but he returns again and again to the secret world in his writing. In 2013, he wrote a Bond novel, Solo, which saw the spy travel to Nigeria, where the author grew up. Writing a character who embraces espionage so wholeheartedly seemed to highlight the way in which the agents in the rest of the Boyd oeuvre tend to be pulled into the secret service reluctantly, their subterfuge speaking of deeper personal struggles.

Gabriel Dax lives in the shadow of an early tragedy. As a child, his house burnt to the ground; he escaped, but his mother died. He is tormented by flaming nightmares, drinks too much, refuses to commit to his working-class girlfriend, Lorraine, who works in a Wimpy and whom he finds “incredibly, tumescently alluring”.

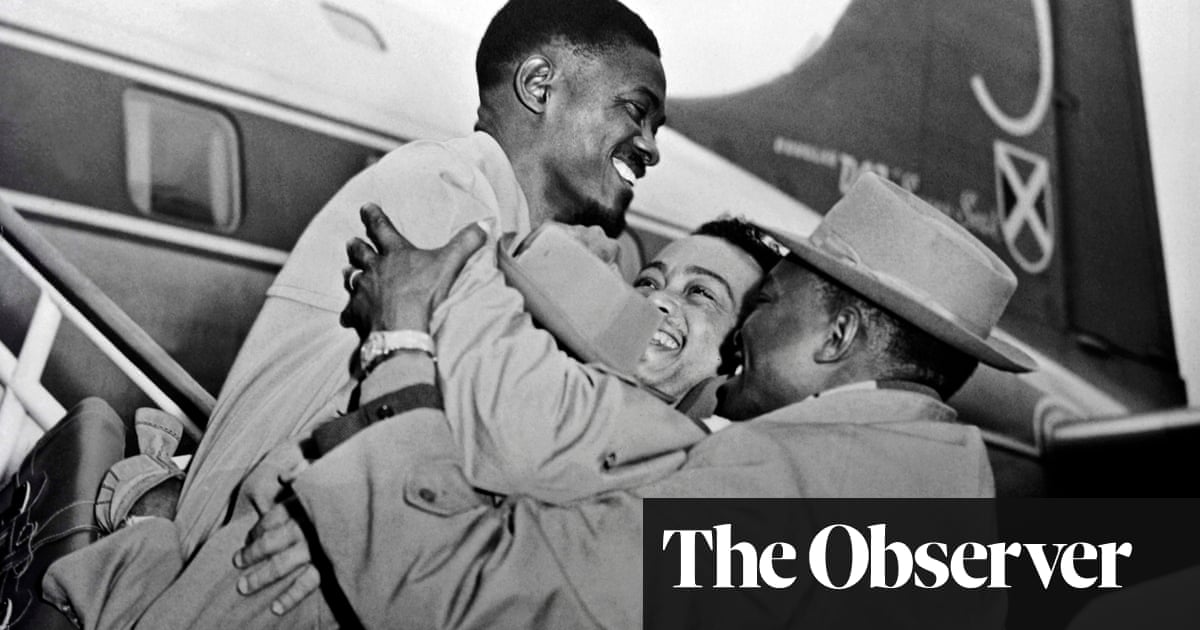

It’s the early 1960s and Dax, a young but celebrated travel writer, is in the Congo to interview its new prime minister, Patrice Lumumba. Lumumba mentions that foreign powers are trying to assassinate him, giving Dax the names of three agents: one American, one British, one Belgian. A few weeks later, with Dax back home in London, the news breaks of Lumumba’s death.

Convolution is one of the great pleasures of the spy novel. Seen from height, the structure of these narratives says: the world is not as it seems. There are connections where you thought there were none; what appears to be coincidence is in fact part of a wider scheme. The untangling of the threads at the end comes with a pleasurable sense of release. Boyd used this generic template masterly in his purest spy novel to date, Restless, in which the ordinary life of Eva, its hero, is transformed and upended by her recruitment as an agent. Gabriel’s Moon is equally sure-footed, comfortably managing at once to deliver all the pleasures of the genre while also subtly undercutting and questioning them.

Gabriel spots an attractive older woman, Faith Green, on his flight back from Africa. She’s reading one of his books. Soon, she’s turning up at his door, revealing that she’s head of an obscure sub-department of MI6, the Institute of Developmental Studies. Their job is to wheedle out double agents (whom they call “termites”). Green asks Gabriel to act as a “messenger boy” for her. The request isn’t a complete surprise – he’s done similar jobs for his brother, the pompous Sefton, who does something shadowy in the Foreign Office.

The story now races off across countries – one day we’re in Cádiz, the next Warsaw – and gives us a broad cast of memorable characters. We get to know the enigmatic Green much better, coming to understand her role in the complicated web that links a Spanish painter called Blanco, a British double agent and an American president. We meet Kit Caldwell, MI6 head of station in Madrid – “worldly, amused, cynical” and often very drunk. We meet the sinister American agent codenamed Raymond Queneau. Gabriel is drawn deeper and deeper into the labyrinth of secrets and betrayals while all the time trying to come to terms – via his analyst – with his childhood trauma.

Martin Amis said that a novelist writes his or her best books between the ages of 35 and 45. But there is something impressive about the energy and life force that the 72-year-old Boyd brings to his novels. I adored the rangy and rollicking The Romantic and here, two years later, is a spy novel every bit as good as Restless. Boyd takes such obvious, infectious pleasure in telling his story, bounding along just in front of the reader, scattering clues and red herrings. I’m not sure that there’s a more reliably entertaining novelist working today.