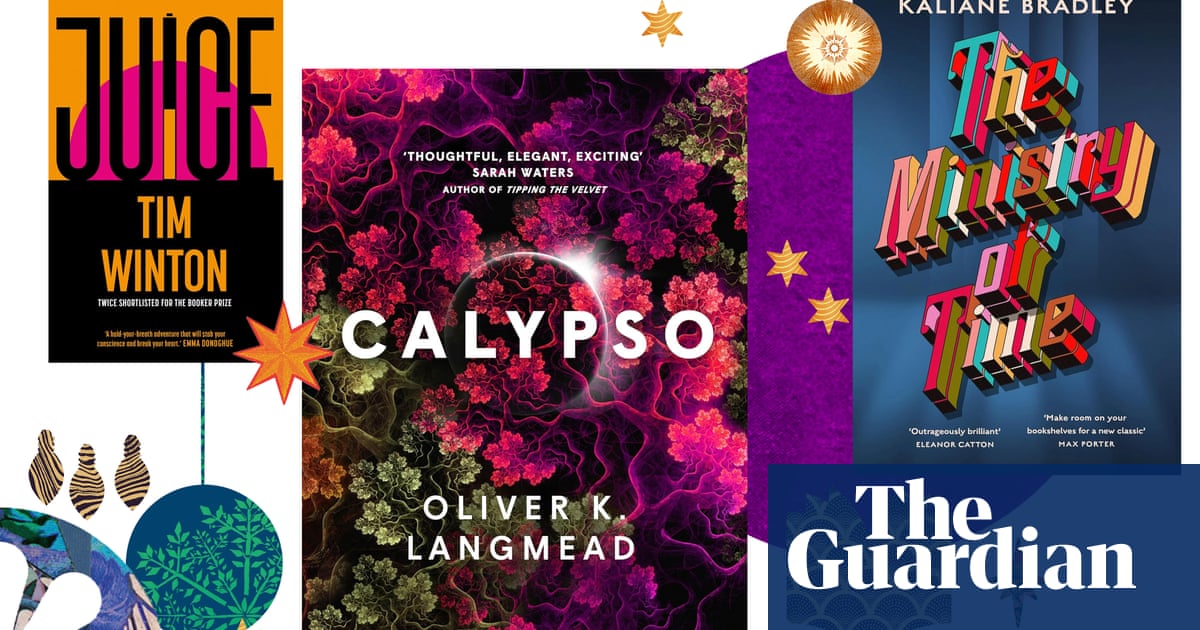

Juice

Tim Winton, Picador

There is no shortage of post-apocalypse dystopias, but Winton’s hefty eco-disaster is a cut above. An unnamed man and a mute young girl flee pursuers across the blasted landscape of future Western Australia. Looking for refuge in an abandoned mine, they are taken hostage by a stranger armed with a crossbow. The man narrates the story of his life, Scheherazade-style, in an attempt to stop this person killing them both – the tension that builds across this long novel as to whether the strategy will save them is brilliantly worked. As the night unfolds, we get the full scope of what it means to live in a ruined world, learning how the epochs of the past declined from The Hundred Years of Light to The Dirty World and The Terror. The architects of the Earth’s collapse, descendants of the corporate polluters from our time, now live in redoubts and bunkers, and part of the story follows “the Service”, a paramilitary group who hunt them down. The prose is gorgeous, as you would expect from Winton, and a passion for our beautiful planet – alongside anger at what corporations are doing to it – burns red-hot throughout.

Three Eight One

Aliya Whiteley, Solaris

Rowena Savalas, a 24th-century information curator, discovers a text that was posted online in the summer of 2024. Built out of multiple sections, each 381 words long, it describes a woman called Fairly’s coming-of-age ritual as she walks the Horned Road, where she is followed by the sinister “Breathing Man”. Is the story fiction or autobiography? What is the significance of the number 381? Fairly’s surreal adventures are annotated by the puzzled Rowena, as she tries to make sense of what’s going on. Enlightenment is neither evaded nor clunkily supplied in Whiteley’s expertly disorienting novel, although the ending is a satisfying rearrangement of our assumptions. A beautifully strange and unique fable.

The Ministry of Time

Kaliane Bradley, Sceptre

A British-Cambodian woman takes a job in the titular ministry, which is investigating the viability of time travel by gathering “temporal expats” from across history. Her task is to look after “1847”: the real-life Commander Graham Gore, who in our world died on the ill-fated Franklin expedition to the Arctic but here has been brought into the 21st century. There’s much fun to be had in showing Gore around modern Britain – he is amazed at washing machines and pop music, astonished to discover that the British empire is no more – and Bradley does this with great charm and wit. But she also does something more: pulling the reader along a thriller narrative as the real purpose of the ministry’s project comes to light; tracing out a compelling love story; and engaging with the toxic heritage of imperialism. Smart, funny and moving, this debut has been the hit of the year.

Calypso

Oliver K Langmead, Titan

This finely crafted verse novel combines hard SF, adventure and philosophical meditation. Calypso is a generation starship, “a grand cathedral / when the sun is out a hollow eclipse / And after dusk a glimmering circlet”’, carrying colonists towards a new world. Engineer Rochelle is woken from centuries-long cryosleep to discover that the ship is now in orbit, but most of the crew are dead; the internal ecosystem has run riot, overgrowing the interior spaces with lush foliage. She pieces together what has happened: a legacy of war between engineers and botanists over how to terraform the new planet. The story inhabits a variety of verse forms including syllabic verse, loose blank verse, alexandrines and concrete poetry; not a gimmick but an integral part of its effectiveness. The form and telling recall Paradise Lost, but the heart of the story is more bucolic: a space-opera eclogue. This is a unique and memorable work.

after newsletter promotion

Toward Eternity

Anton Hur, HarperVia

Scientist Dr Beeko invents a cure for cancer by replacing all the body’s organic material with flawless “nanodroid” cells. The cure is, if anything, too successful, for the nanite-cellular body becomes effectively immortal. At what point, we are asked, does a human stop being their original self? Literature scholar Yonghun, whose body has been remade by Beeko’s technology, teaches an AI how to appreciate poetry, thereby creating a new subjectivity named Panit, whom Beeko uploads into an artificial body, giving it access to the freedom of embodied life. Panit, trained on TS Eliot and Emily Dickinson, sees the universe in terms of poetry. From here the story moves from the near future to the far, as Yonghun, Panit and other “nano humans” replicate and thrive, posing an existential risk to humanity. Or are they themselves now humanity? The novel’s penultimate section, The Very Far Future, extrapolates beyond questions of personhood into interstellar wars, the loss and recovery of language, and deep vistas of space and time, towards the final section, Eternity. Hur’s superbly written novel explores humanity, love, beauty and death with beautiful resonance.