Between 1904 and 1914, the US completed the unprecedented project of connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans via the Panama Canal. Print celebrations of the achievement began to appear almost instantly, some even before the canal was finished. They have not stopped since. The typical Panama Canal book is a panegyric, and many writers have focused on the men who planned, executed, and helmed the project as paragons of power, vision, technical know-how, and ingenuity. The explorer and archaeologist John Lloyd Stephens, who became the president of the wildly profitable Panama railroad; Ferdinand de Lesseps, the French businessman who tried but failed to complete the canal; Phillipe Bunau-Varilla, the French engineer who negotiated the eventual American purchase of the canal company, as well as the canal concession and land in Panama; Theodore Roosevelt, the president who, in his own words, “took Panama”; William Gorgas, the doctor and public health officer who defeated yellow fever; and George Washington Goethals, the general and engineer whose genius for military organization finally made the canal a reality, were the figureheads of the project and its most visible champions. They also received most of the credit when the work was done.

But they did not build the canal all by themselves. The project required tens of thousands of laborers who toiled for years in the tropical heat to cut a trench through the backbone of the American continent. These men came from all over, but principally from the global peripheries, and the majority from the Caribbean. On the canal they made far more money than they could have made at home. But they paid dearly too, dying by the thousands from industrial accidents, landslides, inundations, and tropical diseases. If they were lucky, they returned home merely injured or maimed. While they worked, they endured segregation, race prejudice, and mistreatment at the hands of Americans, Europeans, and Panamanians alike. They also left an indelible stamp on Panama, a tiny Central American country that became, for a few decades at the turn of the 20th century, the focus of the whole world’s attention.

Cristina Henríquez’s new novel, The Great Divide, takes inspiration from this side of the Panama Canal story, following an ensemble of characters drawn to Panama, and the canal, from across the hemisphere. Ada Bunting is a teenage girl from Barbados who stows away on a steamer in search of a job that will help her mother afford surgery for her ailing sister. Omar Aquino is a young Panamanian man who defies his father’s distaste for the Americans and takes a job performing manual labor on the canal works. Marian Oswald, by contrast, is the Tennessee-born wife of an American medical officer tasked with the elimination of malaria who soon falls victim to disease herself. Finally, there are Joaquín, a city-loving fishmonger who works in the central fish market of Panama City, and his wife, Valentina, a reluctant city dweller who learns that the canal plan calls for the elimination and relocation of her hometown of Gatún, which will result in the displacement of her family, friends, and neighbors.

Henríquez tells of everyday people forced to navigate a new world shaped by imperial forces and organized along the lines of science, progress, public health, and engineering, all for the benefit of a fast-integrating capitalist system and a growing US empire. By presenting the perspectives equally of Panamanians, Caribbean migrants, and European and American managers—including those drawn into the canal against their will and those offered no choice but to vacate their homes to make room—Henríquez reminds us that any great project, a canal, a railroad, a nation, even an empire, is vast enough to contain a multitude of stories, and beneath each shimmering totality lies a network of interconnected but individual lives.

Henríquez’s novel is the product of extensive historical research. It also comes amid a boom in scholarship on and depictions of Panama and the canal that foregrounds the contributions of workers, especially those of color; women, especially women of color; and ordinary people, especially Panamanians. Recent histories have been much more suspicious of and even hostile to American imperial power than previous accounts, amending fawning profiles of a handful of great men. Julie Greene’s The Canal Builders (2009), for example, interrogates the experiences of the international labor force, while Noel Maurer and Carlos Yu’s economic history The Big Ditch (2011) details the economic effects of US imperial policy and the later Panamanian administration of the waterway. Michael E. Donoghue’s Borderland on the Isthmus (2014) narrates the history of US administration of the Canal Zone and the structural nature of its conflict with Panamanian sovereignty, while Marixa Lasso’s Erased (2019) recovers the stories of the Panamanian towns within the zone that were moved, inundated, or simply destroyed to make room. Most recently, Joan Flores-Villalobos’s The Silver Women (2023) details the lives and labors of Black Caribbean women living in the Canal Zone, while Kaysha Corinealdi’s Panama in Black (2023) explores the enduring influence and uncertain integration of Afro-Caribbean Panamanians into mainstream Panamanian society. All together, these scholarly works suggest that Panama and the canal remain an important site for inquiry into the nature of work, migration, sovereignty, and imperialism from the turn of the 20th century to the present.

Henríquez’s novel also adds to a rich tradition of literary treatments of the canal that explore the politics of the isthmus’s US-assisted secession from Colombia, US economic and informal imperialism, and the perilous experiences of canal laborers both during and after construction. The Great Divide riffs on the Panamanian genre of novelas canaleras, which consider both the relationship of the country and its people to the US-administered Canal Zone and the marginal role Panamanians have often played in governing their own national territory. In themes and content, The Great Divide most closely mirrors Gil Blas Tejeira’s Pueblos Perdidos (1962), a historical treatment of the entire period of canal construction from the arrival of the French in the early 1880s to the first transit through the US-built canal in 1914. Like Henríquez’s Joaquín and Valentina and their family, Tejeira’s protagonists, a French-Guatemalan-Panamanian family in the Canal Zone, come to reside in Gatún and face the rupture of displacement. But Pueblos Perdidos takes on a longer timeline, 35 years, than Henríquez’s work. Tejeira also makes frequent digressions into the political, social, and economic history of Panama and Colombia, beyond what might be strictly required for the advancement of the narrative.

Henríquez offers no such panoramic account of political developments. But her aim is not to produce a novel of national history or sociological development. Instead, The Great Divide pulls out a cross-section of human experiences to place them under literary examination.

“The Great Divide” succeeds as a novel about the ways that human connection is made both possible and impossible by the imperial system that arrived to govern the Canal Zone.

In The Great Divide, the canal acts as a gravitational force. It draws disparate characters into near relation while touching people living countries or continents away, including some who never travel to Panama at all. Henríquez demonstrates the globe-spanning reach of the canal while remaining tightly focused on what is ultimately a local story. With the exception of a few chapters set in Barbados, the entirety of the book’s action takes place either within the Canal Zone—an area extending five miles on either side of the canal—or in Panama City. Henríquez frequently emphasizes the apposition of events: her characters might not share much in terms of social or political background, but they share a common place and time. As Marian Oswald is catching the cold that will lead to the pneumonia that renders her bedridden for most of the novel, Henríquez directs our gaze to the works taking place just beyond her palatial residence:

Down the hill from where the Oswalds lived, past the train station, past the town of Empire with its machine shops and clubhouse and commissary and post office and stores, down a steep terrace of 154 steps, down, down into the Cordillera Mountains, into the base of a man-made canal that was presently 40 feet deep and 420 feet wide and growing by the day, thousands of men worked in the rain, shoveling mud, wrapping dynamite, laying railroad track, and swinging pickaxes at the sheared rock walls.

Every morning these men, who had come from all over the world—from places like Holland, Spain, Puerto Rico, France, Germany, Cuba, China, India, Turkey, England, Argentina, Peru, Jamaica, St. Lucia, Martinique, Antigua, Trinidad, Grenada, St. Kitts, Nevis, Bermuda, Nassau, and Barbados most of all—converged in one place: The Culebra Cut.

Henríquez shows the thousands of laborers employed on the canal, most moving earth and rock with machines and human muscle. The Culebra Cut was the most difficult part: It involved digging a ditch through the mountains themselves, moving some 100 million cubic yards of earth in the process. Thousands of tons of dynamite were employed to blast through the rock; the rubble was then loaded onto trains and carted away. Henríquez excavates the hard and physically dangerous nature of this work, as well as its effects on the men who did it:

Their hands blistered and bled from squeezing the handles of their picks and their shovels for hours on end. Their legs ached, their shoulders burned, their backs felt as though they were breaking, about to snap in two. They were wet all the time. They could never get dry. They were covered with mud. They could never get clean. Their boots fell apart. They shivered with fever.

Like all industrial labor, employment on the canal is hazardous, even deadly. Henríquez brings readers into the work camps and the mud of the cut, imagining the lives and personalities of the “Panama Men” who traveled to the jungle to make their fortunes and sometimes ended up buried under rubble, in the Canal Zone cemetery on Monkey Hill, or in the overflowing hospitals along the line of the canal.

This emphasis on the experience of canal laborers would be a refreshing change of perspective in itself, but Henríquez also gives us their counterparts: Panama Women. These adventurers, as Flores-Villalobos explains, employed “strategies of regional migration, social reproduction, and entrepreneurial labor [… that] relied on and subsidized the extractive labor economies of expanding imperial ventures throughout the late 19th- and early 20th-century Caribbean”—including Panama. Henríquez presents this gendered world of labor and family ties, emphasizing not only the ways women workers lived in the gaps in the official power of the governing Isthmian Canal Commission but also how the money they earned in Panama continued to shape life back on the islands from which they came, to which not all returned.

We see the world of the Canal Zone woman primarily through the eyes of Ada Bunting, who comes because “in Panama, everyone said, finding work was as easy as plucking apples from trees.” This turns out to be true: On her second day in the country, as she helps a man who has fainted from fever on the street, she is offered a job as an attendant for an ailing woman, who turns out to be Marian Oswald. At the Oswalds’ home she meets Antoinette, another Panama Woman, who had been unable to make ends meet after her husband left her for a younger woman. To financially support a household of eight, Antoinette emigrates from Antigua: “In Panama, someone told her, she could cook half as much and earn twice the amount. As it turned out, that person’s calculations had been off by a bit. In Panama, Antoinette learned, she could cook less than a fifth of what she had been cooking before and earn three times as much.” She triples her earning power, but she trades her family life at home for the solitude of a rented room and the anxiety of leaving her children behind in the care of her brother.

Yet this encounter between two West Indian Panama Women on the make produces not solidarity but animosity: Ada is a threat to Antoinette’s relationship with the Oswalds, and it becomes clear that there may only be room in the house for one of them. Henríquez demonstrates that even outside the formally segregationist strictures of the canal company, the zone’s hierarchies of race, gender, and national origin mean loyalty, obedience, and proximity to white Americanness govern the distribution of economic opportunity—perhaps even more in the informal sectors than for the men who labor on the canal works. Moments of connection, commonality, and solidarity are fleeting: for all the ways the novel draws its characters together, it unites none of them permanently. The canal holds people for only as long as it needs to. With their work done—or their bodies destroyed—characters resign, retire, return home, or die. They leave the Canal Zone and the world that Henríquez imagines within it; almost invariably, their time in Panama marks a distinctive period of their lives, but not the whole of their experience: Panama is a stage, their time as functionaries of empire an interlude.

The Great Divide is engagingly written, though occasionally it makes its meanings a bit too plain, as if Henríquez is at pains to make sure her readers derive the proper lessons from significant scenes. These reveal new traits about a character, deepen the reader’s understanding of plot events, or simply flesh out aspects of the novel’s world. Sometimes, however, Henríquez seems to want to tell us not only what happened but how we ought to think about it.

Take a scene in which a French-born canal doctor, Pierre Renaud, encounters Omar at a funeral procession. He has met Omar before, in fact has treated him in the hospital, but cannot place him exactly: “Pierre thought the boy looked familiar somehow. He squinted and stared, but he could not make the connection, and he decided it was nothing after all. Hired help, perhaps. Who could say?” Pierre is vain, self-important, and anxious, more concerned about his reputation among the better sort of Canal Zone residents than his duty to his patients, or even, it seems, learning much about the world around him. His inability to recognize his former patient, a young Panamanian man, testifies to incuriosity and self-absorption but equally demonstrates the racism that characterizes every aspect of life in the Canal Zone and underwrites a large part of Pierre’s contempt for the people he considers below him. “There were thousands of boys who looked like him here, and certainly he [Pierre] could not be expected to tell one from the next.” Pierre may well have this thought, but it might have been more effective to end the passage earlier and challenge the reader to puzzle out the reason for his sudden lack of interpersonal recall.

The Great Divide succeeds as a novel about the ways that human connection is made both possible and impossible by the imperial system that arrived to govern the Canal Zone. Some characters come to Panama for the canal; for other characters, the canal comes to them. Their lives are changed: they confront the loss of a hometown even as they gain a new country; they expand their world geographically only to find their daily existence reduced to a struggle against the mud, rock, and muck of the Cordillera; they seek professional glory but find only personal misery. What is the great divide? It’s the canal that carves a gap across the continent, severing the land in two. It’s the separation of Panama from Colombia, a political act that granted sovereignty to Panamanians only to make it contingent on the whims of the US. It’s the gulf between the Atlantic and the Pacific sides of the country; between American and Caribbean Colón and Panamanian Panama City. It’s the color line that separates the workers of color and their girlfriends, wives, and children, who live in segregated facilities and receive their payment in silver, from the white and European employees who receive their wages in gold and enjoy better jobs, living conditions, options for recreation, and social prestige. It’s the political borders of the Canal Zone, dividing Panamanians outside the area of imperial interest from those who live within it, under the rule of a foreign government. It’s the gap between the promises of total transformation wrought by technological and political change and the realities of persistent unequal relations of power, wealth, influence, and access to food, medicine, a job, and a safe and secure home. Ultimately, The Great Divide confronts the way the social, political, and economic logics of imperialism cannot help but pull people together even as they must hold them inexorably apart. ![]()

This article was commissioned by Charlotte E. Rosen

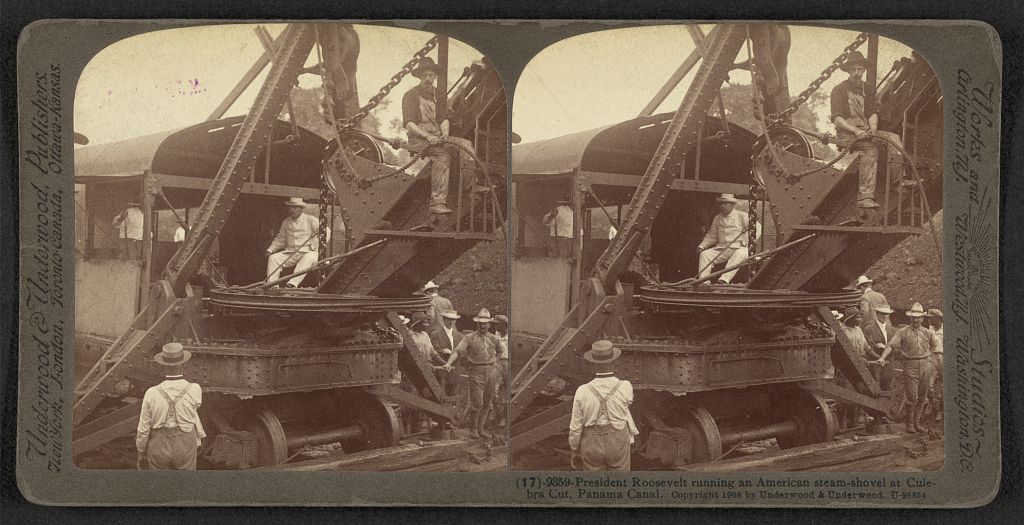

Featured image: President Roosevelt Running an American Steam-shovel at Culebra Cut, Panama Canal (1906). Photograph by Underwood & Underwood / Library of Congress