I am sitting on the stairs of my university lobby with a poet-friend, where SJP and other comrades have erected tents and been camping for six days. Outside, the chants of “Free Palestine” and “No money for genocide” grow louder and louder from the picket. We are talking about students, my age, with comparable mental illnesses, who haven’t shown up to the encampment. Do you think I am doing mentally well? I ask her. She says, No, and says, That’s why you should stay cautious.

My father passed away in September of last year due to a sudden cardiac arrest, a day after my sister’s wedding reception. I had never before seen celebration and mourning so up close, so intertwined together. My sisters and I touched him a last time, the henna stain on our hands still pretty fresh. A week after, I began experiencing panic and anxiety attacks every day.

As soon as I showed signs of mental illness, I began going to therapy, joined a music class (for the first time in my life), hung out with friends frequently, stopped smoking. I ran after anything and everyone that promised sanity, business, a delayed mortality. In the first week of October, Israel began its genocide in Gaza, Palestine, still ongoing nearly a year later. I was still back in Karachi then, among family. I watched news incessantly, like it was going to save me. I stopped sleeping at night.

Attending protests, witnessing others’ grief—which is your own grief too—chanting together, all of these strengthen one’s grief, one’s healing.

When I told my therapist this, she advised me to stop watching distressing videos of men, women, and children being killed. Take breaks. Personally, I find this argument useless, entirely unhelpful. A pigeon shuts its eyes when coming across a cat. Still both the pigeon and the cat exist. But it’s not just the one therapist who advises me this. Many well-intentioned friends have since joined the list.

I attended a translation seminar with other South Asian poets back in January. Kazim Ali, one of the poets in that seminar, author of numerous books, had also recently lost his mother. He said, “The grief is ever present.” It is our losses that bring it to the center. And because grief is ever present, healing is too. And because grief is a collective emotion, healing is too.

Healing does not—cannot—happen in a vacuum. Not when one is healing from trauma, nor when one is coping with an insurmountable loss. Like grief, healing does not have a beginning, a middle, or an end. In fact, attending protests, witnessing others’ grief—which is your own grief too—chanting together, praying Jummah, sitting in Shabbat circle, all of these strengthen one’s grief, one’s healing. It was last Friday, my first Shabbat prayer circle. The leader announced Mourner’s Kaddish, that those who were mourning would stay standing, the rest may be seated. Around the circle, four or five of us were standing. I invoked Baba, I said amen.

Robin Coste Lewis invokes her loved ones who have passed away in the acknowledgment section of her book To The Realization of Perfect Helplessness. Lewis writes: “These are losses I hope to never recover from.” Never recover never means sitting in perpetual despair, “perfect helplessness”—though that is part of it for sure—but means never forgetting these losses, these lives. Always making them fuel action, fuel change.

I am in New York City now, completing my master’s in poetry. And what has poetry taught us, if not this? Over and over and over again, we come undone through our comrades, through companionship. If anything, attending vigils for the martyrs of Gazans and other Palestinians helps me remember Baba. I silently say his name under my breath, light a candle for him among countless children, kiss a tulip and leave it there, like I would leave at his grave in Karachi.

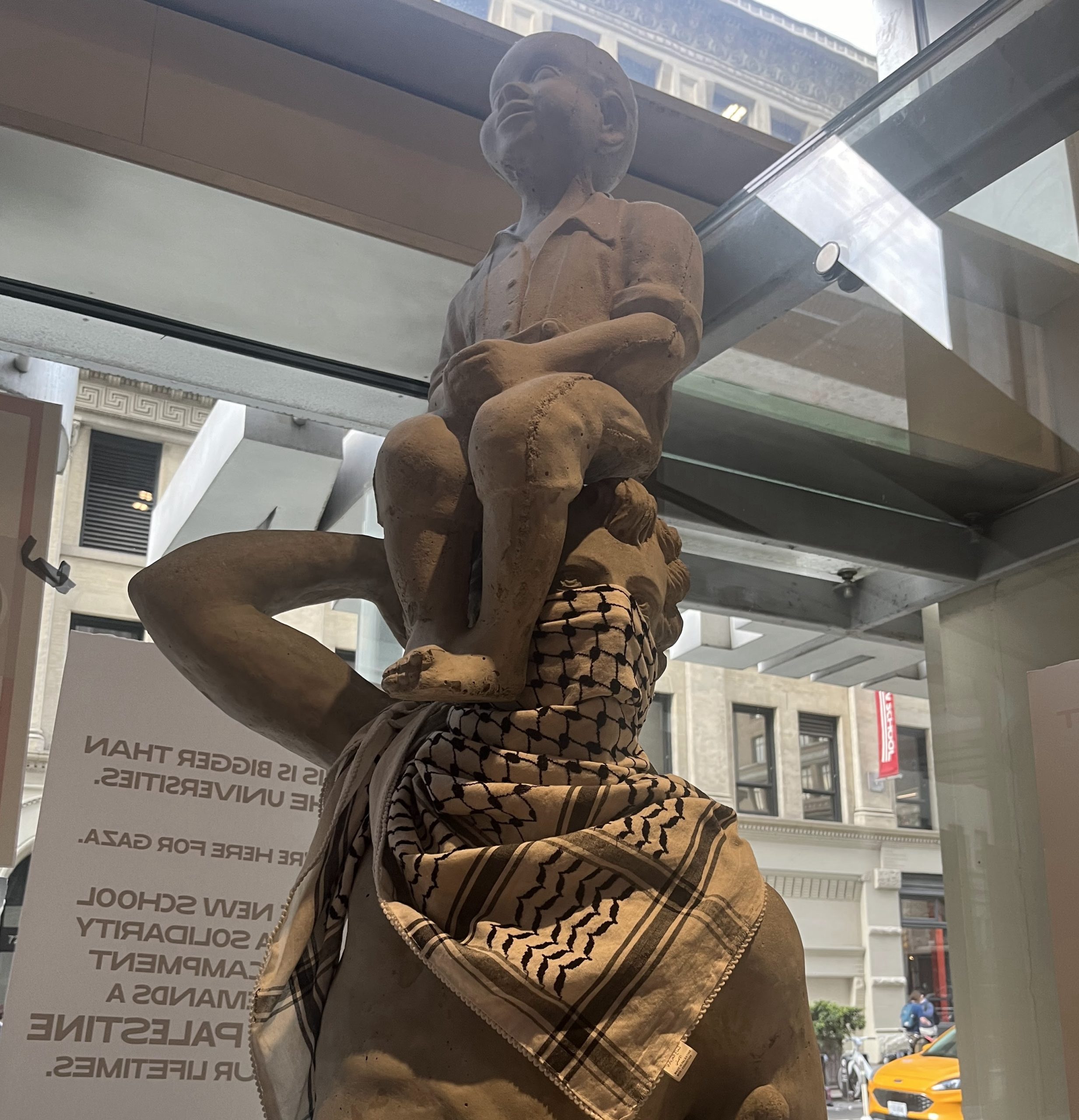

Most (all) of my friends are graduating in a month. Celebration and mourning is once again intertwined. Baba was in the hospital on the night of my sister’s wedding. He insisted the events didn’t pause. I am trying to do what each one of us will struggle to do our entire lives: hold joy and suffering together. Looking at the videos coming out from Columbia’s lawns in which students are wearing keffiyeh and performing dabke gives me joy. Then there are videos of students at OSU being tased and zip-tied by the cops for their encampment. And you know what’s common in both of these? A promise of solidarity among students and comrades, a coming together toward liberation and revolution. At the NYU Gaza Solidarity Encampment, a student comes to the makeshift stage on the shoulder of his comrade. That is how the revolution will be brought: by shouldering each other’s grief and healing. ![]()

Javeria Hasnain is a graduate student at The New School.

Featured image: A statue at the New School dressed with a keffiyeh by Javeria Hasnain.