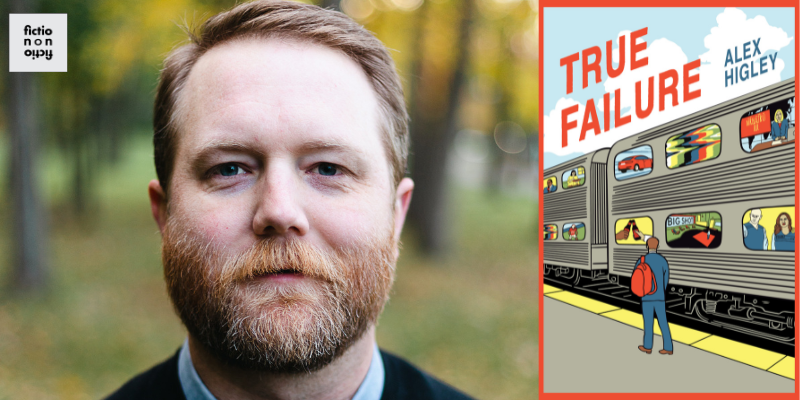

Novelist Alex Higley joins host V.V. Ganeshananthan to talk about his new novel, True Failure, in which a man fired from his job decides not to tell his wife what happened and attempts to change his fortunes by applying to join the cast of a Shark Tank-like show. Higley discusses how he experiences the news in Trump 2.0; lying as avoidance and as emotional refuge; and two big American lies (that an individual can succeed on his own and that we can’t collectively organize to make change). He also talks about Shark Tank as a curated and tidy presentation of entrepreneurship and capitalism, and his choice to have his protagonist focus not on what he will sell or invent, but on how he can bluff his way to what he wants. Higley reads from True Failure.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/. This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan and Whitney Terrell.

*

From the episode:

V.V. Ganeshananthan: So I want to start off by talking about lying in America, which is so vividly portrayed in your book as a real way of life, like a way of dealing with others and also oneself and it gives your book its starting premise as your character, Ben, opens the book having been fired and chooses to lie to his wife, Tara, about it. Can you talk a little bit about when you started working on this book and when you began, what it was about lying and our ways of doing it that caught your imaginative attention?

Alex Higley: Yeah, I think the original kernel of the book came from a couple places. One, you know, my wife and I were, like many couples, one that just had Shark Tank on in the background of our nightly scrolling through nonsense on TV to avoid the headlines, basically. And it was a show that I was always a little bit just repelled by and fascinated by. It just had provided such a curated and neat presentation of entrepreneurship and capitalism, and it made everything seem so tidy that it was disgusting to me. I think in that way, it was something I was drawn to thinking about a little bit more closely, about why I just had such a push, pull towards the program. And the other kind of genesis point was, I was thinking about compartmentalization within my own life, and how different friend groups, different kind of modes of consciousness that you use to get through the day and and how that can end up feeling like lying to one set of people in your life, even unconsciously or totally consciously at times. And so I think those two kinds of initial motors were what got me into thinking about this book and thinking about a character who would try and get on a reality show with very little.

VVG: So what year is this that you’re starting working on the book?

AH: So this is like 2015, 2016.

VVG: Okay, so a rough time, like, a little bit before we started the show, basically with the first time Trump was elected. And also, gosh, now I feel practically nostalgic for that.

AH: I know, I know, I know. Especially as we’re talking today. I mean, the past couple weeks have been so brutal that I share that with you where it feels like minor comparatively back then, I don’t know.

VVG: I mean, it’s terrifying to think that, and yet, as I was reading, I found it pretty painful, actually, to recognize in the character of Ben the kind of the amount of lying it takes to get through the American day, and maybe the amount of lying I personally have normalized for myself to function. I feel like over the past several years, I’ve spent a lot of time talking about truth and the news on the show, but in the wake of Trump taking office, I was kind of thinking about turning it the other way, like, what was the role of lying in this country’s political and emotional life prior to January, and how it has changed since then, certainly at the time that you started writing this book. We’ve been a capitalist system for a long time.

AH: Yeah. I mean, I feel like recently, since the second round of Trump, the absolute onslaught of misinformation, it feels ramped up to me. I mean, it feels like having to search for, you know, truth within any of what is being released through the media, through official channels, or even, you know, places, outlets you trust. I feel like it’s hard to really have any trust residing in them, because so much is parroting misinformation unintentionally a lot of times. So now I feel like it’s so much about deciding what your personal filter is going to be and what your personal approach to dealing with the news is going to be.

I didn’t really know how to deal with it, and I, at the suggestion of a friend, signed up for a few specific newsletters that I’ve been trying to get my news through newsletters, pretty much exclusively, and not seek out headlines in other ways just because, I think to receive the news in that way, to have it mediated through a single person and delivered that way, is helpful for me, but at the same time, I fail all the time with that. You know, there’s no way that you can avoid this onslaught of terrible information and also there’s the balance of wanting to stay informed. So it’s—I don’t have any answers, and if you do, I would love to hear your approach about how you’re dealing with this, my goodness.

VVG: Well, I’m curious to know what newsletters you’re reading at this moment.

AH: The two that are at the forefront of mine are Organizing My Thoughts and Today in Tabs. Those ones I’ve really enjoyed. I mean, enjoyed is a strange way to put it, that’s—I’ve found them to be useful. And then, you know, when you sign a petition or whatever, there’s like the ones that you get automatically signed up for that I feel like I also get through my—we all get, I’m sure, a million of these other types of newsletters that you don’t even consciously sign up for, but that you’re on so, but those two are the ones that I think I’ve found the most useful.

VVG: Yeah, I mean, it’s interesting because I had my, like, regular check-in with a mental health professional this week, and as always, at least since maybe 2016, I asked her—they have the standard depression screen or whatever—I was like, ‘How is that going for your field? Is that still useful?’ And she was like, ‘A lot of people are not doing well.’ I was like, ‘Yeah, no kidding,’ and so I asked, ‘Well, what do you suggest people do?’ And she said, ‘Well, many people limit the news.’ And I thought, ‘That’s not gonna work for me.’

So I mean, I think I understand when people do it, but I think—I don’t know—like, it seems like one way that we lie, and this is a way that appears in the book too, right? Because you’re writing about individuals and systems, so there’s the lie of the American dream, that this is a meritocracy and you have a lot of agency, and then there’s the other lie, which is that collectively, we’re not capable of doing anything or making any change. And those are really a strange pair of lies, actually, right? Like Americans are so well, our country’s so large, and there’s so many systems, and I don’t understand them, and I’m overwhelmed, like, what can I actually do or change? And indeed, many systems are set up to prevent change. So how do you think about that, that individual and collective thing, and then how does that kind of also make its way into the book?

AH: I mean, I feel that’s really central to the book, because both of those ideas, I think, are really deeply baked into American life, and I think it’s why Ben doesn’t think of a smaller movement towards success, a smaller movement towards changing his life. Instead, he feels like it has to be this grand televised gesture, and I think some of which is encouraged by shows like Shark Tank, shows like The Apprentice. Those shows where everything does feel like the striving has to kind of have a very direct and chartable path towards success and the narrative has to be easily told. There has to be a narrative, right?

And I think the reality for so many successful people is—define it how you will—is just that they figured out something small, and were able to kind of keep chipping away. My dad always uses the phrase—he goes, everything’s a job. Just that there’s so many people who have careers that they’ve been able to support themselves with, support families with, where you may not even be familiar, that the job exists. And yet, there’s entire careers that are like that. And I think that in the way that that can be difficult to explain or create a quick narrative for, I think people, some people—definitely Ben in the book—feel the burden of having to have a grand narrative or a direct and easy way to articulate their path towards achieving, and the reality for so many of us, I think, is just that’s not doable.

VVG: So we talk a lot about—I don’t know—there are the people who are not fiction writers who will kind of refer glibly to fiction as lying, and we talk a lot about fictionalizing, and we also talk a lot about lying in the news as it appears and is consumed today on platforms where there’s no fact checking or no editorial review or standards or filters, but we don’t talk as much about lying among those receiving information. So like, limiting the news that that mental health professional was talking about, and Ben is striking, I feel like even really sympathetic, as a character who receives information and lies not only to others but also to himself as this way of coping, and Tara also does this. Like, basically every character does this. Are we all doing this?

AH: I think the easy answer is yes. I think that I’ll speak for myself. In the past when I feel like I’ve caught myself misrepresenting or using lies of omission, just in my everyday life, even in small ways, a lot of times I feel like it’s just to create space for the person that I want to be in my head to exist, whereas I may not feel confident enough to face a problem or a person or a situation head on, and the misrepresentation or the omission can be a way towards being the person that I wish that I was, or wish that I could be. I feel like lies in this way, the kinds of lies that exist in the book are about creating space for oneself, and certainly it’s not an honest approach to it, but I do feel like it’s a way for someone who is not as directly engaged with their agency to kind of almost cosplay what it feels like to have agency in their life. And so, yeah. It’s something that I’ve thought a lot about since writing the book, just having conversations like this about, how is this functioning in my actual life? And it’s one of these things where you answer these questions, and you kind of come away and you’re like, boy, yeah. I think you know, the mental health check in, like you mentioned, I have those too, and definitely a lot of this is coming up.

VVG: I mean, it’s like the illusion of control. I mean, how do you act when it’s—I don’t know—it’s either impossible to apprehend how much control you actually have, or what you know that what you will do will have very little correlation to outcome. And it seems like that’s the way in which capitalism promotes these teleological narratives of cause and effect. I don’t know, I think about the ways in which I often, like, I think I was really bad at plot because I was afraid of cause and effect because there are things that cause other things, and often the relationship between that and a character’s control is so limited. Like you mentioned before, right, Ben, kind of, in his head is like, ‘Well, I got fired, so I’m going to try to get on this TV show.’ And like, there’s no connection, he makes the connection. For him, there’s no in between. He has to have this grand televised gesture, as you say. So not only does Ben want to get on Big Shot, which, as you mentioned, is like Shark Tank, but his approach to getting on the show is really weird and very funny. Can you talk a little bit about his methods and approach?

AH: Yeah. So Ben, I think, related to this idea of being afraid to engage with the agency you may or may not have in your own life. Ben has no idea, has no business, has no hook for getting on the show. He just has this belief that he will, and he ultimately ends up coming up with a very small kind of trick to be able to apply to get on the show, but he has nothing, and really, that is his idea. His idea is to have nothing. And it’s something that—I think the genesis point for that was just seeing the movie Being There so many times, and kind of like taking it in. That kind of “Chauncey Gardiner, Chance the gardener” character who just continually ascends, you know, emperor-no-clothes-type story. I think that was interesting to me. Obviously in our current political environment, that kind of ascent is weaponized against us every day, and so I think probably when I was starting to write this book, that was the other idea, just thinking about that kind of ascent in a different way. Not that I was directly thinking about Trump, but it was in the air. How is this happening? How is this person continuing to do this? I think that’s a very American kind of story, is the faking it ’til you make it, and how real that can be. And so I think from a more absurd and lighter place, in some ways, that’s Ben’s story.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Vianna O’Hara.

*

True Failure (2025) • Old Open (2017) • Cardinal and Other Stories (2017)

Others:

Choice by Neel Mukherjee • Cue the Sun! by Emily Nussbaum • Dana Spiotta • Being There (Film, 1979) • Shark Tank • The Apprentice • Big Brother • Organizing My Thoughts • Today in Tabs • Sally Franson and Emily Nussbaum on Reality TV Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 7, Episode 42