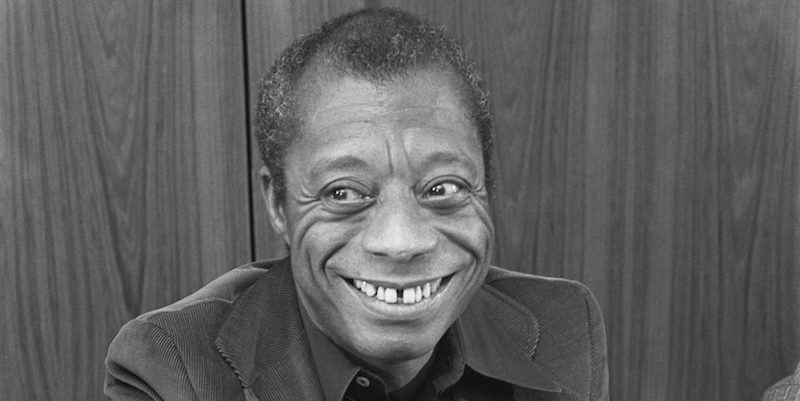

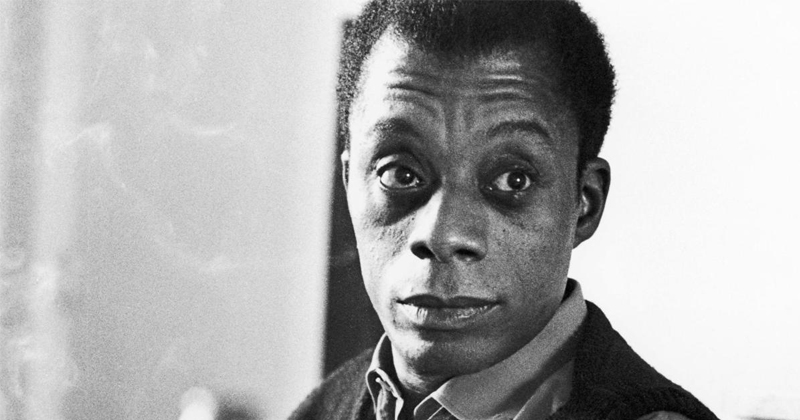

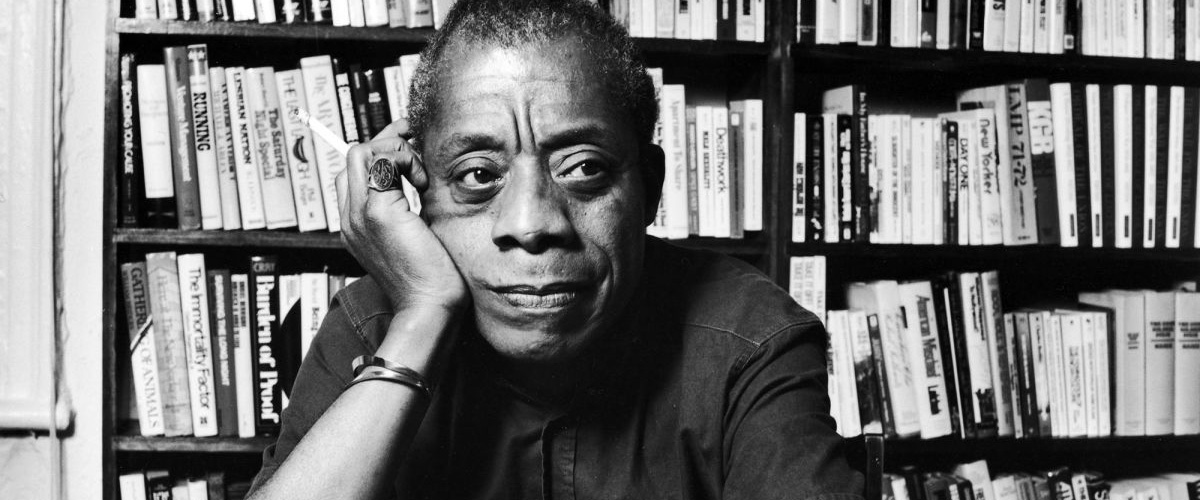

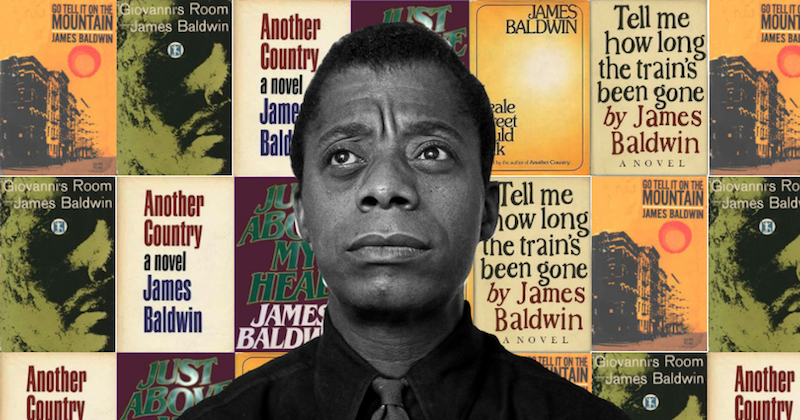

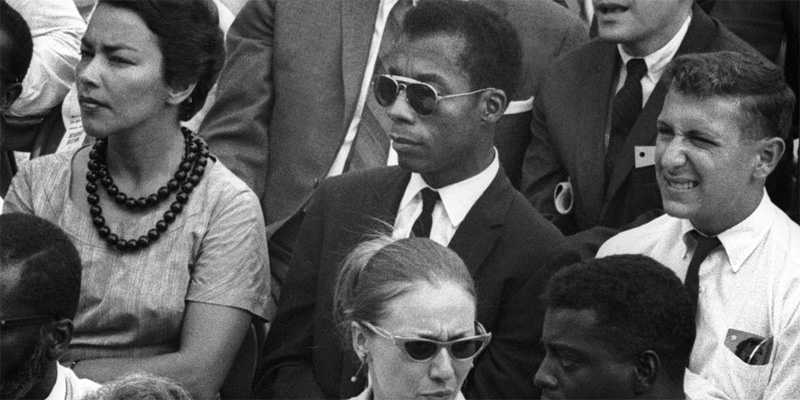

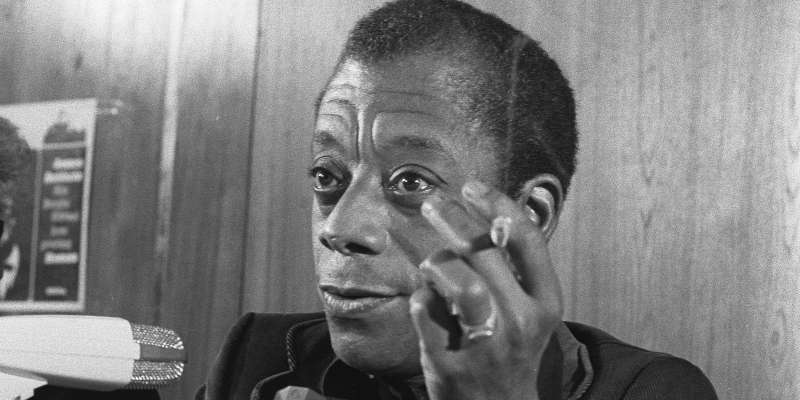

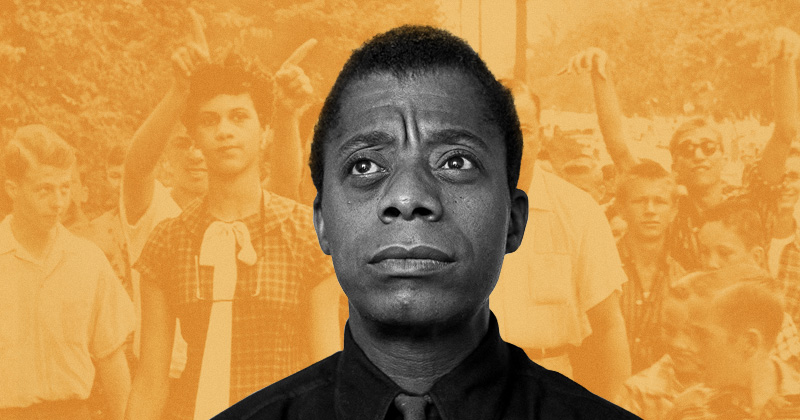

100 years ago, on August 2, 1924 James Baldwin, né James Arthur Jones, was born in New York City. Needless to say, he would grow to become one of America’s most important and beloved writers, thinkers, and social critics; his novels, essays, plays, poems, and criticism are essential reading for anyone who wants to understand this country—or the human condition.

Article continues after advertisement

Though he died in 1987, Baldwin continues to have an outsize, but well deserved, influence on contemporary literature, activism, and criticism. We are grateful for his life and his work. Join Literary Hub in celebrating the centennial of Baldwin’s birth with a few of our favorite pieces on the writer from over the years.

10 reasons to love James Baldwin, in honor of his 100th birthday.

By Brittany Allen

James Baldwin would have turned a hundred years old today. There are far more than a hundred reasons to celebrate the man. A brilliant, complicated author and one of our most fearsome public intellectuals, he left cultural fingerprints everywhere. And not for nothing, his shadow seems to loom larger all the time.

It’s hard to know where to start with a tribute, given the man’s output. So I may as well begin with abject praise. Here are ten reasons to keep celebrating a “Black, poor, gay, and gifted…activist, humanist.”

Towards Universality: On Reading—and Rereading—James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues”

Tom Jenks Considers the Eternal Power of a Masterpiece of American Short Fiction

By Tom Jenks

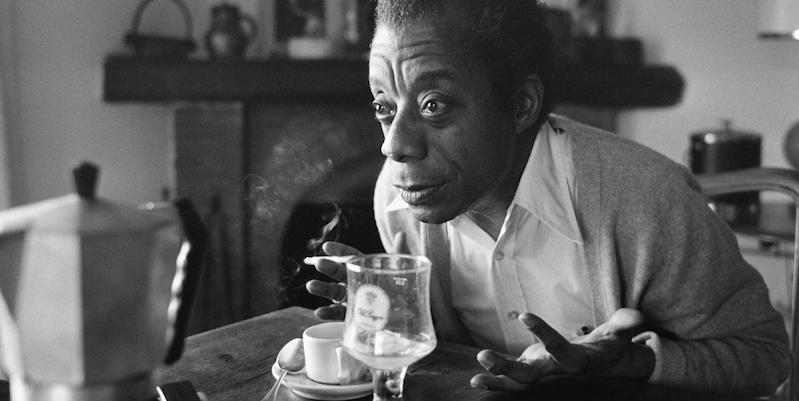

I can’t recall with certainty when I first read James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues,” but I had it well in mind in 1984 when Raymond Carver and I were selecting stories for our American Short Story Masterpieces. When Ray and I worked on our selections, we would meet in Manhattan, where I lived, or in Syracuse, New York, where he lived. Whichever of us had traveled brought a suitcase full of books, and the other contributed an accumulated stack. We’d trade books.

Colm Tóibín on James Baldwin’s Enduring, International Influence

Caoilinn Hughes in Conversation with the Author of “On James Baldwin”

By Caoilinn Hughes

Caoilinn Hughes: To begin at the beginning: there was the word. Both you and Baldwin temporarily heeded it and even preached it, or considered doing so. That early influence of the Church is there so clearly in Baldwin’s use of language, his incredible range and control of register, and it’s there in the temper of your prose, too. Is it fair to say you share that influence?

Colm Tóibín: Enniscorthy, where I grew up, had a very close community and at the very center of it was the Catholic cathedral, and at the very center of that was the altar, at the very center of the altar were the priests, and then behind the priests, the altar boys, and I was an altar boy. So that whole idea of listening to language, as ritual… I was I suppose coming to consciousness really just as the Latin Mass changed to the English Mass, but I was there for the Latin Mass, and bits of the Latin Mass are still in my mind; Sursum corda, lift up your hearts.

And so it starts with being an altar boy for those Masses in Enniscorthy, the stained glass, the light, the Cathedral, the choir, the amazing choir singing Mozart… all of that mattered enormously, as did later at St. Peter’s, which was half a seminary and half a Diocesan school where a lot of the real influences on, certainly on me, were priests. And that came later with its ambiguities, but at the time it was very rich because the Diocesan priests were spending their summers in America because they were teacher-priests.

Therefore they were coming back in 1971 with all that stuff of the Civil Rights Movement and having debates about it. So that when I came to Go Tell It On a Mountain, I was fascinated by the Civil Rights Movement.

The Many Lessons from James Baldwin’s Another Country

Carole Burns Rediscovers a Masterclass in Craft

By Carole Burns

From the first page, I am immersed in the world of James Baldwin’s Another Country.

It is Rufus’s world from the start. Rufus is a flawed character if there ever was one – and yet how deeply sympathetic I feel as he trudges the streets of New York City. Baldwin’s New York is always vivid and complicated and laden with a character’s history as well as its own. In the novel’s opening pages, Rufus revisits his past: The Avenue, the name Baldwin seems to use for every avenue in New York; the jazz bar where, only seven months earlier, Rufus was playing drums instead of looking in as a vagrant. He hopes and fears people inside will recognize him.

James Baldwin: The World is White No Longer

Read “Stranger in the Village” from Notes of a Native Son

By James Baldwin

From all available evidence no black man had ever set foot in this tiny Swiss village before I came. I was told before arriving that I would probably be a “sight” for the village; I took this to mean that people of my complexion were rarely seen in Switzerland, and also that city people are always something of a “sight” outside of the city. It did not occur to me—possibly because I am an American—that there could be people anywhere who had never seen a Negro.

Cornel West on Why James Baldwin Matters More Than Ever

In Conversation with Christopher Lydon

By Christopher Lydon

James Baldwin was the prophetic voice of an era that isn’t over. Fifty years ago he was the intense man from Harlem who wrote, in essays and novels, his version of a civil-rights movement. Over the ruins of the 1960s, and specially the assassination of key leaders, black and white, James Baldwin spoke a sort of furious sad song for his country.

Activist-philosopher Cornel West writes and speaks in the James Baldwin tradition, in books like Race Matters and Black Prophetic Fire. You see him on television between Amy Goodman on Democracy Now and Sean Hannity on Fox, he’s back and forth as a teacher too, at Princeton and now at Harvard. In Andover Hall, the only gothic building on the Harvard campus, we sat down with West to learn about James Baldwin’s resonance today, in “as blues-like a moment as we can imagine.”

James Baldwin Might Have Been Most at Home in Istanbul

Hilal Isler on Finding Home When You’re Not Looking for It

By Hilal Isler

When James Baldwin left home for Europe, he was broke. It was Armistice Day, 1948, when he sailed from New York to Paris, 40 bucks in his pocket. He would say he left not to go to France, but to get away from New York. He left because he had to.

James Baldwin in Paris: On the Virtuosic Shame of Giovanni’s Room

“If France proffered him love, it also bathed him in a peculiar shade of loneliness.”

By Gabrielle Bellot

Early in Giovanni’s Room, James Baldwin’s seminal novelistic exploration of queerness, the narrator, David, remembers the first time he held another man’s body close to his own. He has spent a day with his friend Joey in Brooklyn, astonished at “how good I felt . . . how fond of Joey.” Tired, they decide to spend the night in Joey’s apartment, but Joey finds himself too entranced by his friend’s form in the shadowy room to sleep. When he makes awkward conversation about still being up because a bedbug bit him, David and Joey move closer and closer together, until they are cuddling and kissing. The experience shocks David. “It was like holding in my hand some rare, exhausted, nearly doomed bird which I had miraculously happened to find,” he reflects. The comparison is remarkable; his moments of intimacy with Joey are at once new and old, new in that he is a virgin to this kind of experience, and old because he has been feeling a quiet thrumming of desire all day with Joey, even if he didn’t fully understand the words of that soft electric language inside him. It is a beautiful “miracle” of a moment.

The Last Days of James Baldwin’s House in the South of France

Where Miles Davis, Nina Simone, Stevie Wonder and More Once Met

By Magdalena J. Zaborowska

After my first sighting of Chez Baldwin in 2000, I traveled to other places important to the writer—from the streets of Harlem and Greenwich Village to Paris, to Istanbul, Ankara, and Bodrum—and met many people who knew him and shared living spaces with him, and who all confirmed his paradoxical need for a frantic nomadic lifestyle on the one hand, and, on the other, his fervent desire to establish a stable domestic routine in multiple locations. Intrigued by his late-life turn to domesticity as well as the increasing focus of his works on families, female characters, and black queer home life that are prominent in Just above My Head and The Welcome Table, I returned to Chez Baldwin in June 2014. By that time I had published a book on the writer’s Turkish decade and numerous articles about various aspects of his works.

On Domesticity and Memory in James Baldwin and Becky Suss

Peter L’Official on Suss’s “Brand of Children’s Vision for Adults”

By Peter L’Official

In 1976, James Baldwin published his first and only children’s book, Little Man, Little Man: A Story of Childhood—a collaboration with French artist and illustrator Yoran Cazac. Described on its jacket cover as a “child’s story for adults,” the book drew on Baldwin’s own difficult experiences growing up as a Black boy in Harlem, though it was written partly at the request of another young, Black, New York City “little man.” Baldwin’s nephew, Tejan, would often ask his famous uncle when he would ever write a book about him, to which Baldwin responded in the form of the story’s four-year-old protagonist, TJ. The book, however, was not well-received upon publication.

How Did James Baldwin Become a 21st-Century Influencer?

Marc Lamont Hill and Todd Brewster on the Blessing and Curse of Shareability on Twitter

By Marc Lamont Hill and Todd Brewster

James Baldwin, who came of age as a cultural figure in the 1950s, is a 21st-century influencer.

Two quotes in particular—“Not everything that is faced can be changed; but nothing can be changed until it is faced” and “To be black and conscious in America is to be in a constant state of rage”—have been perhaps the most shared, but it will surprise no one who knows something about the man that scholars have uncovered James Baldwin quotes on Twitter representing multiple sides of the author’s personality. One researcher used reverse engineering to delineate “six subtly different Baldwins” crafted from quotations that have “excised, revised, botched, remediated, and wielded Baldwin’s words anew.”

“Write a Sentence as Clean as a Bone” And Other Advice from James Baldwin

You Can Never Go Wrong Listening to This Guy

By Emily Temple

Ninety-four years after his birth (and more than thirty since his death) James Baldwin remains an intellectual, moral, and creative touchstone for many Americans—whether writers, critics, or simply people trying to live well in the world. Baldwin was an accomplished novelist, a legendary essayist, and an important civil rights activist—and most importantly for our purposes here, the man knew how to write a great sentence. His birthday is as good an excuse as any to revisit some of his teachings about the craft, and to that end, I’ve collected some of his best literary bon mots from essays and interviews below.

A Look Inside James Baldwin’s 1,884 Page FBI File

Memos on “Aliases,” Sexuality, and The Blood Counters

By William J. Maxwell

Baldwin was “Jimmy” to most of his friends and to himself as well when he meditated on the various aspects of his personality. The numerous “strangers called Jimmy Baldwin,” he observed of his own diversity, included an “older brother with all the egotism and rigidity that implies,” a “self-serving little boy,” and “a man” and “a woman, too. There are lots of people there.” This secret FBI summary made the mistake of treating variations on Baldwin’s name and identity as a set of potentially criminal pseudonyms. For the Bureau, “James Baldwin,” “James Arthur Baldwin,” “Jim Baldwin,” and “Jimmy Baldwin” were “aliases” needing correlation and correction.

James Baldwin’s Children’s Book Will Help You See the World with Fresh Eyes

On Reissuing the Quietly Radical Little Man, Little Man

By Nicholas Boggs

2017 was a watershed year for the legacy of James Baldwin. I Am Not Your Negro, directed by Raoul Peck, was nominated for an Oscar for Best Documentary. Barry Jenkins, director of the Oscar-winning feature, Moonlight, announced that his next film will be an adaptation of Baldwin’s 1973 novel, If Beale Street Could Talk. On the front page of the New York Times came the news that the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture acquired a massive archive of Baldwin’s papers, now available for public view. Baldwin’s prophetic words on race relations continue to be quoted and engaged in national and international conversations about race with renewed force and urgency in the era of Black Lives Matter.

It is against this backdrop that a forgotten Baldwin book, entitled Little Man, Little Man: A Story of Childhood, is being republished by Duke University Press today after more than 40 years of obscurity. Originally published in 1976 by Dial Press in the United States and Michael Joseph in London, the book’s formal innovation and subject matter—the lives of black children in Harlem—didn’t resonate with readers at the time, and it went quickly out-of-print, despite the fact that it was profoundly important to Baldwin, who called it a “celebration of the self-esteem of black children.”

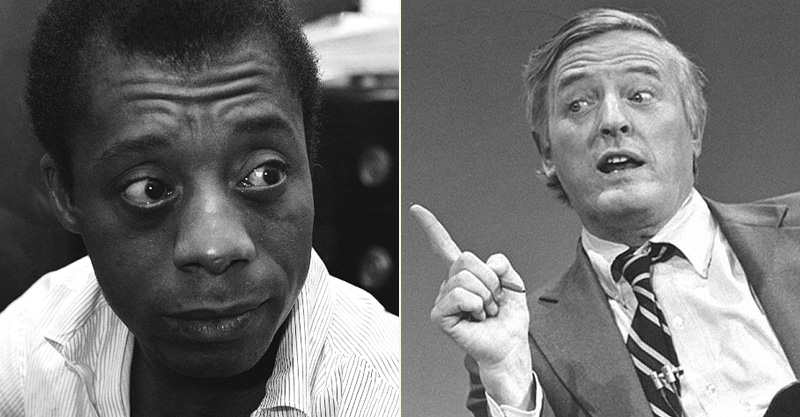

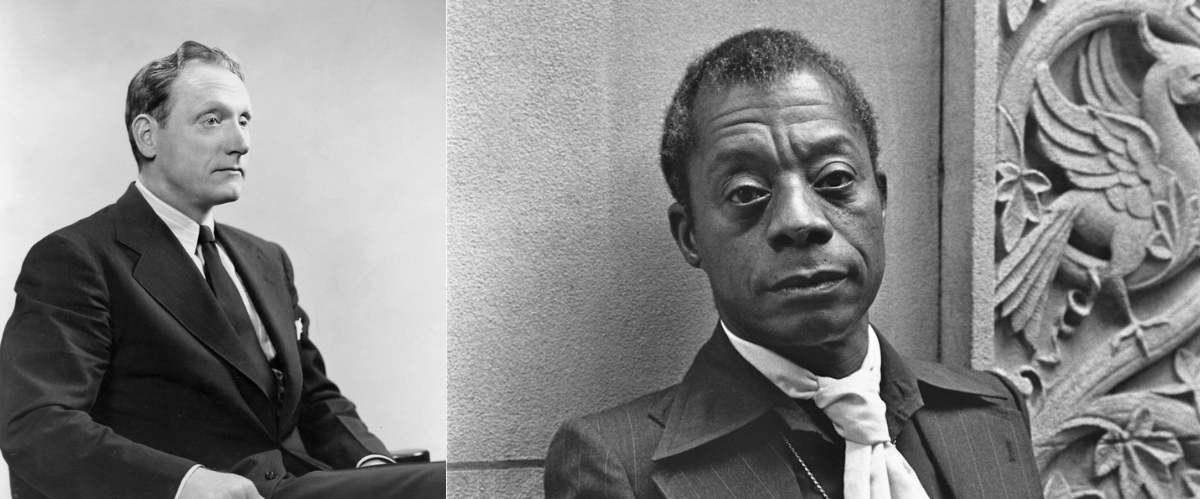

Baldwin vs. Buckley: A Debate We Shouldn’t Need, As Important As Ever

Gabrielle Bellot on America’s Foundational Divide

By Gabrielle Bellot

“It comes as a great shock,” James Baldwin said in his epochal debate against William F. Buckley at Cambridge in 1965, “around the age of five, or six, or seven, to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you.” It was early in the debate. The already-prominent African-American writer was speaking first; his opponent, then the editor of the National Review and soon to become lionized particularly in conservative circles as a father of the American right, stared at Baldwin with the lazy eyes and fingers on chin of a patrician boredom. Baldwin—visibly somewhat awkward at having to defend a proposition he thought obvious, that “the American Dream is at the expense of the American Negro,” which was the debate’s motion—had begun by making a simple, yet necessary point, one that rings as true today, if not truer, than it did in 1965: that the answer to this question ultimately came down to one’s “system of reality.” That a flag may look the same on the surface to you or me, yet where we store it away inside us—what it means to us—differs so drastically as to make two flags out of one. That all flags, in a sense, are perhaps two, or three.

Read the first reviews of every James Baldwin novel.

By Dan Sheehan

James Baldwin is widely considered to be one of the finest writers and public intellectuals this country has ever produced. A brilliant novelist, essayist, and social critic, his explorations of homosexuality, racism, and class struggle in America have had a profound influence on the work of a generation of socially conscious authors, as well as countless readers and contemporary civil rights activists.

Totally, Radically Baldwin: Raoul Peck on I Am Not Your Negro

Craig Hubert Interviews the Director about his Oscar-Nominated Documentary

By Craig Hubert

In 1979, the writer James Baldwin began working on a new project. “Remember This House” was originally conceived as a piece written for The New Yorker that would be a tour through Baldwin’s memory of the civil rights movement. The article never happened—parts of the original idea eventually migrated to Pat Hartley & Dick Fontaine’s documentary I Heard it Through the Grapevine (1982)—but as the decade progressed, Baldwin kept returning to project, over and over again. It became the foundation of a book proposal that was never completed, now focused on the intersecting lives of civil rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr., and a film project with the Maysles Brothers that was discussed before Baldwin’s death in 1987.

When the Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck began developing a film about James Baldwin around 2006, with the assistance of the author’s estate, he saw the unfinished “Remember This House” as the crucial centerpiece that, because of its cumulative stature and open-endedness, allowed him to bring Baldwin into conversation with a present-day audience. As a teenager, Peck had been transformed by Baldwin’s words, partly because there was a direct connection between writer and reader that couldn’t be found anywhere else. It felt like Baldwin was speaking right to him, and the film needed that same immediacy and focus.

“It has absolutely nothing going for it, except Satan.” Read James Baldwin on The Exorcist.

by Emily Temple

Though James Baldwin is best known and loved for his novels, essays, and oratory, he is not frequently remembered as a great film critic—though, as Noah Berlatsky wrote in The Atlantic, he should be. In 1976, Baldwin published The Devil Finds Work, a book-length essay about his life watching movies, and about the politics of art in America, and nature of film itself.

On James Baldwin’s Radical Writing for Playboy Magazine

Masculine Fantasy and the Subversive Possibilities of Androgyny

By Joseph Vogel

James Baldwin submitted an essay, “Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood,” to Walter Lowe Jr., the first African American editor of Playboy magazine. Its radical thesis—that misguided notions of masculinity were at the root of America’s moral quandary—was new for Baldwin (at least in emphasis) and a direct challenge to the magazine’s primary demographic.

I Squatted James Baldwin’s House in Order to Save It

Shannon Cain on Preserving a Literary Legend’s Last Address

By Shannon Cain

To clean the floor of James Baldwin’s guest room would take 32 disposable cleaning wipes. I figured this out on my hands and knees, estimating the square footage of the terra cotta tile surface. There were 40 wipes in the package. If I used one wipe per roughly two square feet, I’d have enough. I was camping here without running water or electricity, but damned if I was going to live inside a dusty mess.

Behind the Dedications: James Baldwin

The People in His Life and In His Books…

By Arvind Dilawar

James Baldwin was, undoubtedly, a compassionate man. A Pentecostal junior minister in his teen years, Baldwin eventually left the church, but the Christian ideal of brotherly love suffused his writing. It is, for example, what he turns to at the conclusion of his essay “Notes of a Native Son” to confront the ongoing violence and indignity of racism in the United States, writing: “Hatred, which could destroy so much, never failed to destroy the man who hated and this was an immutable law.”

Baldwin’s work is not only full of compassion for humanity at large, but love for the individuals in his life as well. His affection is found in the fictional portrayals of actual people in his short stories, plays and novels, such as the semi-autobiographical Go Tell It on the Mountain. It’s present in the references to his family members and friends in his essays and articles. It is perhaps most conspicuous in the dedications of his books—although these inscriptions, without context, elude appreciation.

James Patterson Remembers the Time James Baldwin Fought Norman Mailer

“They were arguing loudly, fists clenched, looking like they were ready to rumble.”

By James Patterson

My first New York literary party taught me that, like a lot of secret societies, the inner world of literary people was borderline crazy and completely overrated.

“What If We Weren’t Afraid to Tell the Hard Truths?” Chris Chalk on Playing James Baldwin

“Being Baldwin requires you to be free. It’s mandatory.”

by Dan Sheehan

Chris Chalk may not be a household name just yet, but he’s on the cusp.

The North Carolina native burst onto the American theater scene in 2010 when he starred opposite Denzel Washington and Viola Davis in the Tony Award-winning Broadway revival of August Wilson’s Fences. Since then, you may have seen his supporting turns in 12 Years a Slave, Detroit, Justified, Homeland, The Newsroom, or Gotham. Most recently, Chalk played Paul Drake—a troubled beat cop turned private investigator in 1930s Los Angeles—opposite Matthew Rhys in HBO’s acclaimed reboot of Perry Mason.

In Capote Vs. the Swans, the second season of the Ryan Murphy’s venomous anthology series Feud, Chalk plays none other than James Baldwin, who, in 1975, pays a flying visit to his old friend Truman Capote (Tom Hollander) in the midst of the latter’s alcoholic exile from New York high society.

“James Baldwin writes down to nobody.” Read Langston Hughes’ 1958 Review of Notes of a Native Son

“He is trying very hard to write up to himself.”

“I think that one definition of the great artist might be the creator who projects the biggest dream in terms of the least person. There is something in Cervantes or Shakespeare, Beethoven or Rembrandt or Louis Armstrong that millions can understand. The American native son who signs his name James Baldwin is quite a ways off from fitting such a definition of a great artist in writing, but he is not as far off as many another writer who deals in picture captions of journalese in the hope of capturing and retaining a wide public. James Baldwin writes down to nobody, and he is trying very hard to write up to himself. As an essayist he is thought-provoking, tantalizing, irritating, abusing and amusing. And he uses words as the sea uses waves, to flow and beat, advance and retreat, rise and take a bow in disappearing.”

Blacks and Jews: Fifty-Five Years After James Baldwin’s “Negroes Are Anti-Semitic Because They’re Anti-White”

Terrence L. Johnson and Jacques Berlinerblau Dissect a Classic American Polemic, Still Relevant Today

By Jacques Berlinerblau and Terrence L. Johnson

James Baldwin’s landmark essay “Negroes Are Anti-Semitic Because They’re Anti-White” is alternatively nuanced and strident, exacting and scattershot, hopeful and fatalistic. It’s fairly prophetic too. As we mark the 55th anniversary of its publication let us acknowledge that, in spite of all the outrage (and confusion) the piece created, it was prescient in many ways.

Way back in April of 1967 Baldwin surmised that by being white,Jewish-Americans—even the many Jewish-Americans committed to social justice—were ensnared within a brutal system of what we now call “racial capitalism.” The economic asymmetries that the system engendered would, in Baldwin’s augury, doom the civil rights coalition that these minority groups had heroically forged. Too, these structural inequalities would corrode any authentic empathy Jews and Blacks may have felt for one another.

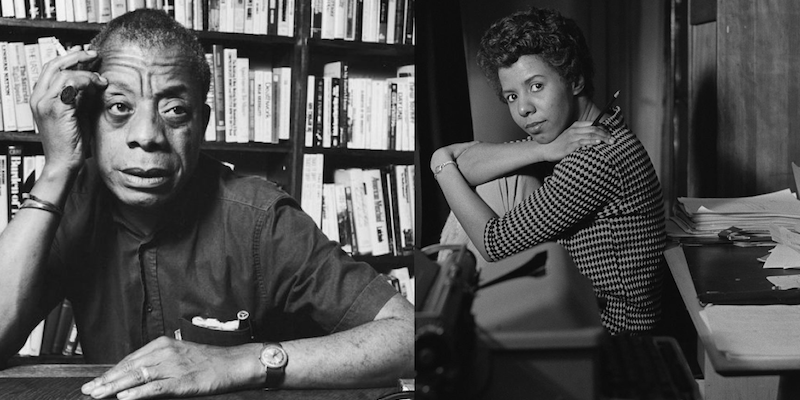

Charles J. Shields on the Profound and Playful Friendship Between Lorraine Hansberry and James Baldwin

“Baldwin loved her caustic wit.”

By Charles J. Shields

During that year of intense writing and rewriting, Hansberry became friends with James Baldwin. They met in April, at a workshop reading at the Actors Studio of his novel Giovanni’s Room, which he had adapted into a play. The work is about an interracial love affair. In America, Baldwin said, “the sexual question and the racial question have always been intertwined.” Lorraine went out of curiosity.

Watch this never-aired ABC television profile of James Baldwin.

By Walker Caplan

Thank goodness for archives. A Closer Look, Inc., a project of storied producer and documentarian Joseph Lovett, has made it their mission to promote health- and social justice-related historical materials through film—and among said materials is an unaired ABC 20/20 profile on James Baldwin from 1979, when the show was still new.

On James Baldwin’s Unflinching Exposé of American Greed and Racial Terror

Eddie Glaude Jr. Rereads Nothing Personal

By Eddie Glaude Jr.

Nothing Personal is an extraordinary piece of writing—perhaps one of James Baldwin’s most complex essays. In a moment of profound transition in his life as a “witness” and within the compact space of four relatively brief sections, Baldwin lays bare many of the central themes of his corpus. He writes about history, identity, death, and loneliness. The reader gets a sense of the depth of his despair and his desperate hold on to the power of love in what is, by any measure, a loveless world—especially in a country so obsessed with money. In a sense, Nothing Personal sits at the crossroads of his work. The Fire Next Time solidified his fame and status as one of America’s most insightful writers about race and democracy, but the brutal reality of the black freedom struggle—the murder of Medgar Evers, for example, and the terror of Southern sheriffs—forced him to confront, again, the country’s ongoing betrayal. Baldwin, like a conductor approaching a railway switch, signals with this essay the beginning of a shift in tone. Darkness hovers over the writing. One feels his vulnerability on the page.

A Dinner in France, 1973: Josephine Baker, James Baldwin, and a Very Young Henry Louis Gates, Jr

Harmony Holiday on the Public-Private Tensions of Black Life in America

By Harmony Holiday

In the summer of 1973 Time magazine decided not to run a piece that it had commissioned, a conversation between James Baldwin and Josephine Baker about the African American experience of expatriate life. Time claimed the pair was “passé,” a couple of relics. Henry Louis Gates Jr., then 22, having just graduated from Yale and been hired as summer correspondent for Time, had conducted the interview in France as part of a longer series on Black expatriates, investigating why they’d remained in self-imposed exile even after the civil rights gains of the 1960s. And Time helped answer Gates’s question for him, making blatant then what remains clear today: America doesn’t respect Black people. Gates would take the dismissal of his piece and its subjects as further evidence that he could accomplish more as a critic than a reporter to help shape the public’s sense of Black culture outside and beyond the media’s preoccupation with fads and bottom lines.

The transcription we are left with feels abridged, but it blooms with a sense of intimacy as we accompany Gates on his assignment, first to Josephine’s favorite restaurant in Monte Carlo—where she lives with her 12 children—and then to Baldwin’s residence in St. Paul de Vence, where the three of them share a long night of wine, food, and discussion that begins with Gates moved to tears at just being in his hero Jimmy’s presence.

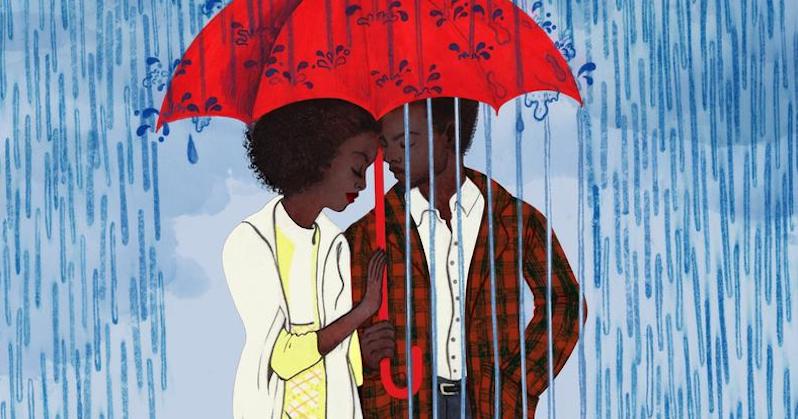

Breaking Down the Roiling, Emotional Middle of a James Baldwin Narrative

Daniel Joshua Rubin on If Beale Street Could Talk

By Daniel Joshua Rubin

All parts of your story are difficult to write. There are infinite possibilities for every choice—where to set the scene, what the characters say, what happens, and how everyone responds. None of it is easy. But generally speaking, it is simpler to craft the narrative for your beginning and ending than the middle, because its purpose is not as simple to define. In the beginning you set up and ask the Central Dramatic Question (CDQ). In the end, you answer it. But what do you do in the middle?

You give your readers an experience. You give them the purest form of the experience that you promised. If your story is a drama, you tear their hearts out. If it’s a comedy, you make them burst out laughing. If it’s horror, you terrify them. You amplify emotion and crank up spectacle. Your audience didn’t come for a lecture; they came to feel. It’s here, in the dead center of your story, that you hit them hard. This will keep it from dragging and give them what they came for.

The Vow James Baldwin Made to Young Civil Rights Activists

Eddie Glaude on How Baldwin Confronted America’s Most Exceptional Lie

By Eddie Glaude Jr.

James Baldwin and Stokely Carmichael first met during the heady days of the movement to desegregate the South. Carmichael was a young activist and a member of a student group at Howard University called the Nonviolent Action Group (NAG), which sought to combat racism and segregation in Washington, D.C., and in the surrounding areas of Virginia and Maryland.

NAG offered a snapshot of the civil rights movement’s future: Carmichael’s fellow students in the group included Courtland Cox, Michael Thelwell, Muriel Tillinghast, and Ruth Brown, all of whom would go on to be influential leaders in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). On Howard’s campus, NAG sponsored a series of programs called Project Awareness, which was designed to explore the full complexity and richness of black life and to engage the controversies surrounding the black freedom movement. It was through these programs that James Baldwin was invited to campus.

James Baldwin: ‘I Can’t Accept Western Values Because They Don’t Accept Me’

In a 1964 Interview with Robert Penn Warren

Robert Penn Warren: In what sense, Mr. James Baldwin, do you think the Negro revolution is a revolution?

James Baldwin: Well that’s a tough one to answer because I’m not always sure that the word “revolution” is the right word. I myself use it because I don’t know of any other. It’s not as simple as a revolution of one class against another, for example. It is not as clear-cut as the Algerian revolution against the French. It is a very peculiar revolution because, in order to succeed at all, it has to have as its aim the reestablishment of the Union. And a great, radical shift in American mores, in the American way of life. Not only does it apply to the Negro, obviously, but it applies to every citizen in the country. This is a very tall order and desperately dangerous, but inevitable in my view because of the nature of the American Negro’s relationship to the rest of the country, of all these generations, and the attitudes the country’s had toward him, which always was, but now has become overtly and concretely, intolerable.

James Baldwin: ‘I Never Intended to Become an Essayist’

From a Classic Interview with David C. Estes

David C. Estes: Why did you take on the project to write about Wayne Williams and the Atlanta child murders? What did you expect to find when you began the research for The Evidence of Things Not Seen?

James Baldwin: It was thrown into my lap. I had not thought about doing it at all. My friend Walter Lowe of Playboy wrote me in the south of France to think about doing an essay concerning this case, about which I knew very little. There had not been very much in the French press. So I didn’t quite know what was there, although it bugged me. I was a little afraid to do it, to go to Atlanta. Not because of Atlanta—I’d been there before—but because I was afraid to get involved in it and I wasn’t sure I wanted to look any further.

What Barry Jenkins Missed in His Adaptation of If Beale Street Could Talk

Gabrielle Bellot Thinks James Baldwin Deserves Better

By Gabrielle Bellot

“I had no childhood,” James Baldwin informed a French journalist in 1974. “I was born dead.” The dark sentiment seemed to reflect Baldwin’s own despair over his childhood; his family was poor, his parents were restrictive, he felt torturously out of place in the narrow world of church and school his parents wished him to occupy, and he learnt, from early on, that his blackness made him both invisible to white Americans in certain situations and monstrously, dangerously present in others.

Why James Baldwin Went to the South and What It Meant to Him

“Everybody Else was Paying Their Dues, and it was Time I Went Home and Paid Mine”

By Ed Pavlić

In the fall of 1957, James Baldwin made his first trip to the Deep South. In complex ways and for even more complex reasons, he was returning to a place he’d never been before. Soon upon his arrival, he found himself surrounded by mirrors. “Everywhere he turns,” wrote Baldwin in “Letter from the South: Nobody Knows My Name,” “the revenant finds himself reflected.” For the readers of the Partisan Review, he recalled his first impressions: a northern Black man arriving in the South “sees, in effect, his ancestors, who, in everything they do and are, proclaim his inescapable identity.”

Possibly because Baldwin arrived in the South after a prolonged sojourn in Europe, and possibly because his vision was calibrated to framing redemptive confrontations, he continued: “And the Northern Negro in the South sees, whatever he or anyone else may wish to believe, that his ancestors are both white and black. The white men, flesh of his flesh, hate him for that very reason.” Completing the scan of his new environment in a way that forecast a strange, maybe perilous, trip through what for him would be a kind of no man’s land, Baldwin wrote: “On the other hand, there is scarcely any way for him to join the black community in the South: for both he and this community are in the grip of the immense illusion that their state is more miserable than his own.”

The Joy and Terror of Translating James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room

Elena Marcu on Bringing an American Classic to Romania

By Elena Marcu

I stand at the window of this small apartment in the south of Romania as night falls, the night which is leading me to hold Camera lui Giovanni (Giovanni’s Room) in my hands.

I started writing this piece right before James Baldwin’s second novel had finally come out here, 61 years after its first publication, and for weeks this was all it said to me, this little pun, a childish echo of the first sentence in the book.

“I stand at the window of this great house in the south of France as night falls, the night which is leading me to the most terrible morning of my life.”

I still don’t know what to say about translating Giovanni’s Room. I have tried to articulate it to my friends. But each time I say something different. I say something incomplete. When I speak, the book does not. When the book speaks, I remain mute. The book speaks better than I ever could.

The Anti-Colonial Vision of James Baldwin’s Last Two Unfinished Works

Bill Mullen on The Welcome Table and No Papers for Muhammad

By Bill V. Mullen

In 1985, Baldwin’s published and some unpublished essays were gathered in a single volume titled The Price of the Ticket. The book was significant for both looking backward, retrospectively and in a monumental manner, at the whole of Baldwin’s life, and forward, to the beginnings of the process of his memory and commemoration. By 1985, Baldwin’s literary production had become relatively meager. He was tired, winding down, traveling less, and camping out mainly at St. Paul-de-Vence. The lover he had lost to AIDS, according to David Leeming, died with him there, his ashes scattered around the property’s garden.