As a writer of both prose and poetry, I love to read work that falls between genres. Whether it’s fiction that leans into lyricism so unabashedly it should be called a poem, or a poem so loaded with narrative that it is, in effect, a lyrical essay, I celebrate the merging of poetry and plot to get at some otherwise inexpressible truth. I admire anyone who can write so transcendently that the lines between genres break down so it’s impossible to know what genre you’re reading in and, more importantly, it no longer matters.

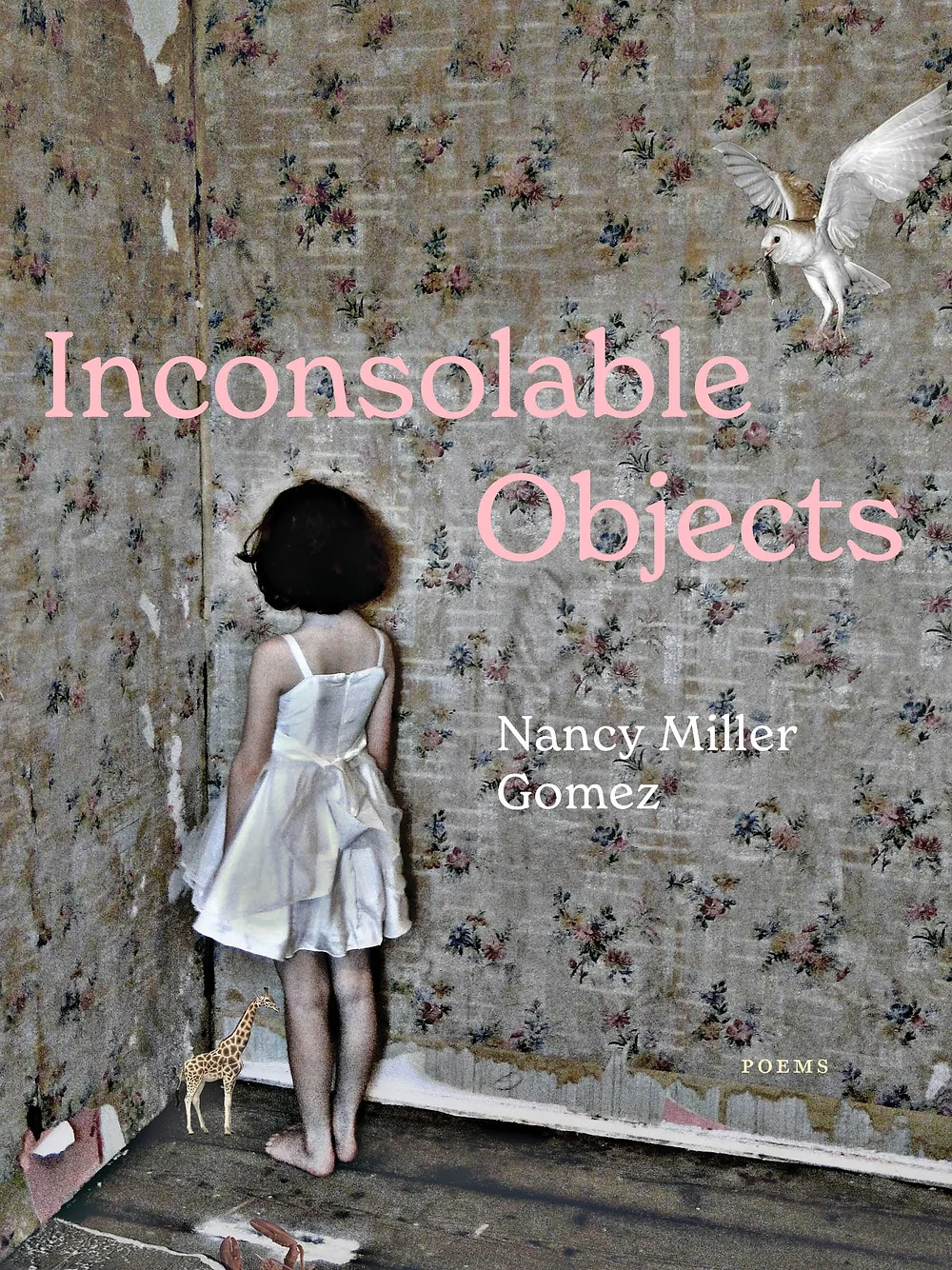

While my debut poetry collection, Inconsolable Objects, falls squarely onto the poetry side of the line, everything I write is informed by a desire to tell a story, and every poem in my collection began with a narrative impulse honed into poetry. And yet, if I’d given the narrative a little bit more headroom, those poems could easily have crossed the line into prose.

Here, I present to you a highly incomplete list of books I love that live in the liminal space between genres and could be shelved in poetry, fiction, or creative non-fiction.

The Smile at the Foot of the Ladder by Henry Miller

In his epilogue to this story, Henry Miller writes: “a clown is a poet in action. He is the story which he enacts.” Miller further states, “it is the strangest story I have yet written.” I initially encountered this little book in my father’s library when I was twelve. I was mesmerized by the language but didn’t know what to make of it. Was it a story or poem? While I couldn’t reconcile the intergeneric language, I was entranced by Miller’s tragic fable about Augustine, a clown who attempts “to depict the miracle of ascension.” Each night before an adoring crowd, Augustine falls into a trance. He is a man driven to impart not just laughter, but everlasting joy, and the ending, as with many poems, is both mysterious and devastating.

Can’t and Won’t by Lydia Davis

Poetry Foundation describes Lydia Davis as a short story writer, novelist, and a translator. That feels to me a bit like describing Mondrian as someone who paints lines, boxes, and squares. Lydia Davis’s writing cannot be defined by the traditional forms because her writing isn’t constrained by the typical dance moves of fiction. While she thinks of herself as a writer of fiction, it’s easy to see why she might be mistaken for a poet. Some of her stories are only one or two lines long and she freely uses enjambment and broken lines. In her essay collection Essays One, she says of her work: “…if, eventually, some of my work comes right up to the line (if there is one) that separates a piece of prose from a poem, and even crosses it, the approach to that line is through the realm of fiction.”

Tinkers by Paul Harding

Yes, I know that Tinkers is squarely considered to be a novel and Paul Harding a novelist. Yes, the book won the Pulitzer for Fiction. And yet, I defy anyone who reads it to say it isn’t pure, incandescent poetry. The story, which weaves the tale of a tinker who “imagined himself somewhat of a poet” with the hallucinatory flashbacks of a dying man (his estranged son), is so lyrical you might fill a notebook with all the memorable sentences you’ll want to keep in your treasure box of beautiful writing.

Bluets by Maggie Nelson

Another indescribable genre-defying work crafted out of 240 numbered paragraphs (or prose poems) that navigate loss and love and profound grief through the lens of someone obsessed with the color blue. Nelson builds her book from borrowed sources: philosophy, psychology, art and music are mixed in with deeply personal observations often framed as questions. Like the elements of a great list poem, each paragraph not only functions as a whole unto itself but simultaneously as a part of the larger whole of the entire book. While the book isn’t an easy read, it offers up immense rewards.

The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros

The House on Mango Street is a series of linked poetic vignettes, a story told in the voice and language of poetry by the twelve-year-old Chicana protagonist, Esperanza as she comes of age in a working-class neighborhood in Chicago.

In one eloquent passage, Cisneros writes: “In English my name means hope. In Spanish it means too many letters. It means sadness, it means waiting. It is like the number nine. A muddy color. It is the Mexican records my father plays on Sunday mornings when he is shaving, songs like sobbing. It was my great-grandmother’s name and now it is mine.”

Citizen by Claudia Rankine

Citizen is the first book on this list typically shelved in with the poetry. Because it is poetry, and Claudia Rankine is one of our finest poets. But Citizen is more than just a book-length poem. It is often called a hybrid work of prose-poetry. And yes, it is that. But Claudia Rankine wrangles language into an entirely new form that doesn’t fit into any clear-cut notions of what we consider poetry or prose. She writes into that liminal space between genres to get at the lived experience of enduring daily microaggressions and being othered in America. An epic tale, a tragic, and profound work of art that bends language to the task of making the indescribable toll of being a marginalized citizen visible.

Train Dreams by Denis Johnson

Before Denis Johnson wrote his epic Pulitzer Prize winning novels, he studied poetry at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. In Train Dreams, he finally merges the two genres into a lyrical tale that moves and breathes and thinks like a poem while capturing the hardscrabble lives and struggle of the men who built the old West in a time of rapid transformation.

Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill

On reading the first few pages of Offill’s exquisite story of a relationship as told by an unnamed narrator, one might be confused. Wait, this isn’t a novel, this is something else entirely. Offill shrugs off the expected trappings of a novel in prose and writes in short bursts of imagistic word-crafting that might have you convinced you are reading a poem. It’s like taking a bite of something expecting to taste one thing and discovering it is something else. And yet, this is a deft and compellingly told narrative that tracks a marriage from early courtship to heartbreak and back again.

At the Bottom of the River by Jamaica Kincaid

Set primarily in Antigua, this book explores mother-daughter relationships, colonialism, gender, and coming of age. This slight collection of stories is more poem-like than many poems that call themselves poems. Yes, they are stories too, but they are clearly, unequivocally poems. The first story, “Girl,” is a poem of advice to a girl from some anonymous narrator, presumably her mother. It is a short punchy list of anaphoric declarations and guidance that accumulate and leave the reader breathless.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.