Coming-of-age stories are typically defined as the transition from childhood to adulthood, which is why we most commonly imagine teens and young adults at their center. But growing out of our formative childhood patterns can happen at any age, and, for many of us, the most profound periods of transformation hit well into adulthood.

A woman’s thirties and forties can be particularly charged. According to many doctors, 35 is the age that women’s fertility begins to drop significantly, forcing us to contemplate what can feel like a life-changing decision for the first time, and one that may put us starkly at odds with societal expectations. Many 30+ women today find themselves in a life that looks very different from typical narratives of “successful” womanhood, resulting in a grating sense of failure and uncertainty. But while motherhood is a common avenue for transformation at this age, it’s important to remember that non-motherhood—the forced awakenings and hard earned growth that comes from sitting with the self—is, too. When we enter middle-age without the standard domestic trappings so commonly portrayed in the popular narratives of womanhood, a deeper understanding of the self awaits, along with a reorganizing of priorities, as we begin to set and trust who we are and what we want, cultural expectations aside.

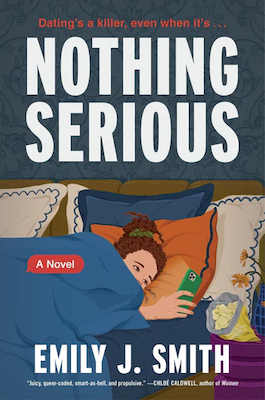

Edie, the main character in my debut novel, Nothing Serious, is a single, thirty-five year old woman reckoning with a life built on chasing the approval of men. Throughout her career—studying engineering, attending business school, working in tech—her instinct to fit in with the men around her has served as an asset, even cosplaying as confidence, but it has also left her hollow, unable to access genuine desire beyond the desire to please. The book is, at its core, a story of self-discovery, learning to untangle from a deep need to prove herself to others, to chase “success” on other people’s terms, to trust herself, instead, and in doing so redefine who she is and what it is she wants.

The list below celebrates women in their thirties and forties who, rather than conforming to the traditional paths of marriage and motherhood, embark on transformative journeys of self-discovery while choosing a life without children.

Grown Ups by Emma Jane Unsworth

Jenny McLaine is an anxious 35-year-old, eager to please and always over-analyzing. The first page starts with her agonizing over captioning the photo of her morning croissant (settling on “CROISSANT, WOO! #CROISSANT”). But Emma Jane Unsworth’s unwavering humor does not distract from the poignancy in this laugh-out-loud novel. Jenny’s journalism career is floundering, and her personal relationships begin to unravel after a breakup with her longtime boyfriend, Art. Prone to extreme self-criticism as a result of her mother’s judgmental eye, Jenny feels like a failure at the very point in her life when she imagined it would all be coming together. She takes solace in a parasocial relationship with an online influencer that only serves to heighten her insecurities and self-doubt. The book follow Jenny as she learns to face her issues-head on, build her sense of self, and define, then trust, her own version of success.

Motherhood by Sheila Heti

Through philosophical contemplations on identity and art, conversations with her partner and friends, musings on her personal and family history, and a technique involving The I Ching—asking questions and flipping coins—the narrator of Motherhood takes us on a cyclical journey through one of life’s most important decisions: whether or not to have a child.

Before I knew much about this book, I was afraid to pick it up, assuming from the title that it was yet another contemplation on motherhood ending with the woman choosing to have children. If you share this concern let me dispel your worries with a necessary spoiler: the narrator decides that having a child is ultimately not for her. There are no formal conclusions, only the making of an inevitable and highly personal decision that broadens our definition and considerations of motherhood and life itself in the painstaking process of choosing.

Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner

Lauren Willowes (affectionately Lolly, to her family) lives carefree in the English countryside until the death of her beloved father. Unmarried in her late-twenties, she is sent to live with her older brother and his family in London. There, she spends years helping him care for his children, fading into the background of their family, and yearning for the rural landscape of her childhood. Lolly is well into her forties when she decides—to the shock and disapproval of her family—to live on her own in a town she has only heard of (endearingly called Great Mop). The family warns her against such a rash decision, encouraging her to stay in London, but she insists. Thus ensues one of the most charming and classic romps of a woman carving out a life on her own. Once settled in Great Mop, she even encounters the devil, with whom she has apparently made a pact, in order to achieve her life of freedom, and happily embraces her role as Witch. Who among us has not longed to escape it all, buy a little cottage in the mountains, and build a life anew?

I’m a Fan by Sheena Patel

The unnamed narrator is in the midst of an impassioned, albeit doomed, affair with a man referred to only as “the man I want to be with.” That man happens to be partnered with a wealthy, glamorous woman we know only as ”the woman I’m obsessed with.” The narrator’s obsession exposes her own insecurities, imagining the woman—who we become intimate with by way of social media stalking—to be everything the narrator is not. At that same time, she is entranced by the man’s manipulative charm, though he is frequently distant and sometime harmful. In addition to revealing reflections on the self, these masterfully rendered obsessions are a tool to observe the way society elevates some and marginalizes others, specifically in terms of race, class, and wealth. We watch as the narrator falls deeper into self-destruction until her wreckage catalyzes an awareness of the patterns she’s stuck in and, importantly, the societal forces that make it so hard to escape. This book has a voice like no other, veering almost into poetry in its form, a stream-of-consciousness that’s somehow both chaotic and immaculate.

Big Swiss by Jen Beagin

Greta, Big Swiss’s 45-year-old main character, resides in a run-down, unheated farmhouse, occasionally infested with bees, in the increasingly gentrifying town of Hudson in upstate New York. Greta does transcription work for money and while transcribing sessions for Om, Hudson’s premiere (and only) sex therapist, she becomes fascinated by one of his clients, Flavia, whom she affectionately calls “Big Swiss.” It’s all a fun and intriguing escape until she recognizes Bis Swiss’s voice at the dog park, and a real relationship between the two women begins. As their intimacy grows, however, Flavia reveals part of her past that Greta is already intimate with from transcribing her therapy sessions, leaving Greta in the duplicitous and deceiving position of hiding how much she really knows. As their relationship grows in this kooky, smart, and darkly hilarious tale, the tension increases, until Greta is forced to confront her own issues and actions. In doing so, she begins to see how her own trauma has shaped her life, bringing her closer to accountability and self-acceptance.

I Love Dick by Chris Kraus

This book is the essential text for neurotic women—and I mean that as the highest compliment. Immediately, we’re thrown into the unconventional, brilliant setup of this epistolary novel. Chris, a 39-year-old filmmaker, and her husband, Sylvère, an academic, move to a small town in Texas, where they meet Dick, a professor, to whom they are instantly drawn. After meeting, the couple begins an elaborate series of letters to Dick, as a vehicle for their own contemplations on life and art and self. Through her infatuation, which grows over the course of the novel— first stimulating, then straining, her marriage—Chris confronts her internalized misogyny and the effects of the patriarchy on the way her art is perceived and on the way she perceives herself. Her infatuation with Dick, which appears self-destructive and uncontrolled, ultimately acts as the mechanism for her own self-actualization. Kraus uses her own abjection—a state often imposed on women, especially as they age—as clay to shape and transform, leading to both a personal metamorphosis and a masterful work of art. She doesn’t shy away from the reality of living in a “man’s world,” but she strides in with open arms, seeing it for what it is, then subverts it so profoundly.

In so many of these stories, we see how, into middle age, we remain trapped in the assumptions that shaped us as children, and how the catalysts typically associated with youth, can, if we’re brave enough to surrender to them, transform us at any age. As Chris reflects in I Love Dick, “It was interesting…to plummet back into the psychosis of adolescence.”

The Woman Upstairs by Claire Messud

The Woman Upstairs is the quintessential novel of a single woman who feels, as she enters middle age, that her life has not gone as planned. Nora Eldridge is a 42-year old-artist by night, school teacher by day. The book opens with an unforgettable internal monologue of rage and regret about becoming what she calls the “woman upstairs”—the quiet, reliable helper for the people around her, fading into a background of mediocrity. But her life is disrupted by the arrival of a new student in her third-grade class, Reza Shahid, who she becomes enamored by, along with his glamorous parents. Reza’s mother is a successful artist who frequently invites Nora to work with her in her studio, where they form a tight artistic bond, and his father is an intellectual and charming Harvard professor. Her obsession with the Shahid family is all-consuming until cracks begin to form. When Nora discovers a devastating betrayal, her idolization of the family starts to crumble, leaving her not only with a clearer picture of the Shahids, but a clearer picture of herself, one that sets her on a path of change and resolve.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.