Article continues after advertisement

Our basket of brilliant reviews this week includes Samantha Hunt on Mariana Enriquez’s A Sunny Place for Shady People, Tope Folarin on Rumaan Alam’s Entitlement, Dwight Garner on Tony Tulathimutte’s Rejection, and Sandra Newman on Will Self’s Elaine.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s home for book reviews.

*

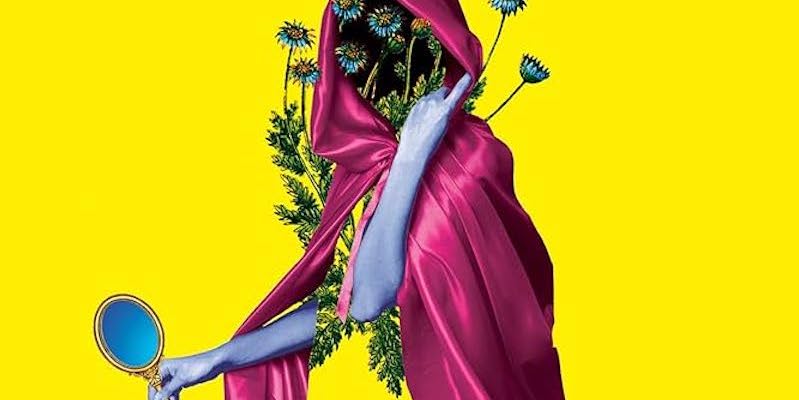

“‘How do you run from something that doesn’t exist?’ the Argentine writer Mariana Enriquez asks in her new story collection, A Sunny Place for Shady People. She then fills her 12 scorching pieces with enough horror to make this reaction seem reasonable, no matter the puzzling immateriality that causes us to flee. I begged my family’s pardon multiple times while reading, gasps escaping from my mouth. The horror in Enriquez’s work is never gratuitous. It drops a supernatural lens over our actual monsters: misogyny, dictators, corruption, cruelty, sexual violence, addiction and poverty. A Sunny Place for Shady People maintains an intimate, sisterly relationship with horror.

It is close and familiar; we touch its skin casually, nearly lovingly … the thrill of reading her short stories comes in tracking her obsessions across tales: rotting faces, dangerous fashion, art that entrances, and bodies—sexual bodies, sick bodies, distorted bodies, dead bodies. These eerie echoes are rewards for our attention—though, really, it’s hard not to pay attention here as each step forward feels wildly dangerous … Perhaps the worst horror is in pretending the source of our fears can be buried, ignored or dismissed as supernatural. ‘Those who think they see ghosts are those who do not want to see the night,’ Maurice Blanchot wrote. Enriquez illuminates both the night and the ghosts, and she rejects her characters’ paralysis. She refuses silence and crafts stories so searing they cannot be buried or ignored.”

–Samantha Hunt on Mariana Enriquez’s A Sunny Place for Shady People (The New York Times Book Review)

“At its best, Creation Lake essays an absurd but subtle analysis of antinomies arising between anti-capitalist and environmental politics. At its weakest, it feels like a bet-hedging period study of same … In part, Kushner has written a novel in which the lineaments of present fascism are visible but blurry, not yet resolved … A novel about political violence and protest, shady state operations farmed out to the private sector, far-right appropriation of traditionally left-wing ideals: it all seems very apropos for 2024. (Kushner, who has written vividly about the plight of Palestinians, includes a fleeting reference to a protest against links between US industry and the Israeli government.)

Yet for all its fizzing voice and narrative texture, its intellectual curiosity, Kushner’s clever skew on genre-fiction conventions, and the ways 2013 may function as allegory of today, something in Creation Lake remains muffled and distant. Interviewed about this book, Kushner has spoken about not wanting to judge her characters or their ideas. Admirable, essential position for a novelist—except that when the stakes are caricatured to a choice between fanciful primitivism, cynical individualism, and faceless capital, then the writer’s irresolution may seem less heroic. (Is it still a novel of ideas if the ideas are mostly bad ones?) Rachel Kushner on more urgent or intractable tensions in radical politics today—that is a story (or essay) to look forward to.”

–Brian Dillon on Rachel Kushner’s Creation Lake (4Columns)

“Entitlement, a barbed, voluble book, is about how certain immutable traits, sex and race among them, persist as fundamental forces that shape our lives no matter how we might attempt to deny or overlook them. It’s also about what happens when status becomes a placeholder for identity … We learn surprisingly little about Brooke’s internal life throughout the novel; Alam doesn’t reveal many of her preoccupations beyond her dedication to impressing Asher—and, as the novel progresses, her goal of purchasing an apartment despite her limited funds. She remains merely a sketch, a vector of ambition…This is a core element of the novel, but also a narrative shortcoming: We don’t get to know her, because she doesn’t really know herself … Entitlement captures this dilemma, showing that although ambition and intelligence may open doors, the ultimate prize—true autonomy and agency—remains elusive for almost everyone. Brooke’s journey is a poignant reminder that, for most people, entitlement is not an identity but a trap.”

–Tope Folarin on Rumaan Alam’s Entitlement (The Atlantic)

“If Tony Tulathimutte’s new book, a collection of linked stories titled Rejection, were a futuristic pop-up book, up would jump unflattering sex pics, medicine for cauliflower acne, unreturned texts, hateful pet birds, the Stanford alumni magazine, terrible food, the odors of crotches and armpits, semi-satirical Judith Butler Halloween costumes and holograms of ‘friends’ who are either poseurs or users or toxic grievance collectors. This book is so cold and lonely you could hang meat in it. Rejection is not an ironic title. Elizabeth Hardwick wrote that poverty, in the form of multiple occupancy, has ‘a marigold odor.’ Does abjection have a smell? If so, add it to the list above …

I read Rejection during a week when I felt down, and it almost stubbed me out, like a cigarette. If it were an Instagram friend, I would have unfollowed it. But Tulathimutte is such an acutely observant writer that I was entranced by his book despite its narrowness and emotional barbarity. One of Tulathimutte’s primal topics is online culture and its diseased repercussions, and he writes about these things in the way Anthony Bourdain wrote about restaurants, Hunter S. Thompson wrote about motorcycle gangs and Molly Ivins wrote about water-headed Texas politicians. He’s alert, in other words; he’s tanked up, bleakly funny and always stropping his knife … Even the losers get lucky sometimes, Tom Petty advised us. Not here.”

–Dwight Garner on Tony Tulathimutte’s Rejection (The New York Times)

“Elaine is a Jewish-American housewife, married to an Ivy League academic, living a densely frustrated life the reader intimately, even claustrophobically shares. The narration is close third person, infused with Elaine’s scabrous, wailing, unsparingly filthy, energetically misanthropic, casually brilliant voice … Haunted by the persistent idea of murdering her son, she reflects, ‘Thinking such vile things … is what gives me this mean expression: the two deep grooves running from my forehead to either side of my hateful nose.’ It’s an extraordinary portrait of the female soul under the conditions of 20th-century misogyny … Elaine is the very model of an unlikable narrator; she’s degraded and her company often feels degrading. But she’s also witty and exhilaratingly blunt, and her darkest opinions are often right on the money. We ultimately come to admire her, as we might an incorrigible friend. In exposing all the dirtiest laundry of his mother’s psyche, Self has perversely elevated and honoured her. Elaine is not just a serious work of art, but an unexpected act of filial generosity.”

–Sandra Newman on Will Self’s Elaine (The Guardian)