When I first heard a Joni Mitchell song, it didn’t sound like any other music. It wasn’t only that the songs moved differently from chord to chord, or that the chords called attention to unexpected notes, or that their words mattered, calling up pictures. It was a sense that the songs were reaching at every turn, pushing up against limit. They were acts of discovery—and living documents of that process.

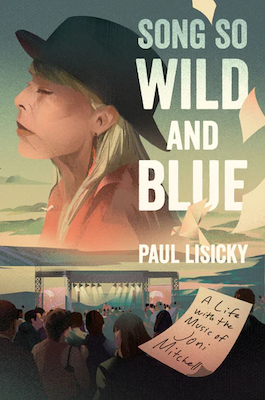

My book Song So Wild and Blue: A Life with the Music of Joni Mitchell chronicles how Joni’s music shapes my life and my art, from my beginnings as a songwriter to my work as a prose writer. She shows me that self-invention is never simple. She isn’t ever interested in defining and isolating her signature moves and getting better at them over time. Rather, she remakes herself as soon as things feel too fixed, as a way to keep curious, open, awake. The Joni of Blue might as well be a different person from the Joni of Court and Spark, even though the albums were released only two and a half years apart.

These ten novels and nonfiction books—I think of Song So Wild and Blue as a fellow traveler—explore the invention of self through music, each one making life out of bent notes, new chords, silences, broken strings. They might ask different questions from mine, but we’re all walking parallel roads.

Coming Through Slaughter by Michael Ondatjee

Coming Through Slaughter re-assembles the life of Buddy Bolden, an early twentieth century New Orleans jazz musician, whose music went unrecorded. Over the course of the novel, Buddy’s fragmenting psyche is echoed by the form of the book, in abrupt tonal shifts, photographs, prose poems, and lists, unspooling any expectation of a straightforward narrative. In a late passage, the writer—a version of Michael Ondatjee—speaks directly about his connections to the wrenching emotional landscape of this world and the pressure points that compelled him to write the book. Coming Through Slaughter walks the thin line between self-creation and self-destruction, embodying jazz’s imperative towards improvisation and on-the-spotness.

The Final Revival of Opal and Nev by Dawnie Walton

Dawnie Walton’s The Final Revival of Opal and Nev accomplishes the nearly impossible: it evokes the adventures of a fictional 1970s Afropunk duo with such style, precision, and conviction that it’s tempting to look up their recordings and performances on Spotify and YouTube. It manages this feat through an invented oral history, a chorus of multiple voices: the manuscript’s editor, the musicians themselves, and their collaborators. Some speak at length. Some break in for a line or two. The story feels energized by the novel’s architecture, as though its liberation could have only come from trying out then rejecting established structures. The same might also be said of Opal herself, whose protest against a label mate’s racism makes it clear that the costs are higher for Black women musicians who dare to say no.

I’ve Had to Think Up a Way to Survive: On Trauma, Persistence, and Dolly Parton by Lynn Melnick

With magnetic directness, poet Lynn Melnick recalls waiting to be checked into rehab at fourteen, listening to Dolly Parton. “The multifaceted clarity of her voice,” she writes, “hooked me instantly. I needed to feel that euphoria in my body again.” In a book structured as a playlist, each chapter named after a Parton song, Melnick offers insight into the ongoing work of reclaiming herself after rape and abuse in childhood. She does more here than connect her personal story to Dolly Parton’s. Her book gives the reader the tools for making meaning of perilous times, as she lays out the impact of misogyny and violence on the culture at large, all the while honoring the singular voice that powers her resilience: “I felt desperate to lose myself in it, and to find myself there as well.”

Nocturnes: Five Stories of Music and Nightfall by Kazuo Ishiguro

Nobel Prize winner Kazuo Ishiguro had plans to be a singer-songwriter in his youth, studying the work of Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen, even sending demo tapes to record companies, but left music behind when he turned to writing. Music still influences his work, however, through its first-person intimacies and his desire to “approach meaning subtly, sometimes by nudging it into the spaces between lines.” Part novel, part story cycle, Nocturnes explores the rift between music’s optimistic reach and the practical. That perspective illuminates “Cellists,” the fifth and final story, in which a cellist takes lessons from an older woman who claims to be a famous virtuoso. Before long he finds out that this is a fiction: she refuses to compromise her genius by playing her instrument—in fact, she hasn’t played in years. This is a book finally about the cost of delusion when it comes to giving oneself over to a life in art.

Sounds Like Titanic: A Memoir by Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman

Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman’s Sounds Like Titanic, a finalist for the 2019 National Book Critics Circle Award in Autobiography, chronicles her college years when she accepts a position as a violinist while struggling to pay tuition. The work is lucrative, but there is a catch: the mics are off when the ensemble performs for audiences, recorded music piped in through speakers. What are the consequences of participating in deceit? Dedicated to those with “average talents and above-average desires,” Sounds Like Titanic explores what it is to live in a consumer culture that prizes outsize dreams over the often mundane, grueling work of developing raw talent. Performance is the doorway through which it thinks about ambition, talent, gender, and competition.

Stone Arabia by Dana Spiotta

Denise attends to her brother Nik with a combination of skepticism, puzzlement, wit, and warmth as he painstakingly documents what might have been his rock stardom: the bands he belonged to, the albums recorded, an invented autobiography. How do you endure middle age after you’ve been nearly famous, your major-label record deal implodes, and you’ve missed your moment? Dana Spiotta’s Stone Arabia, a Finalist for the 2011 National Book Critics Circle Award in Fiction, is a novel that dares to ask if art must be evaluated by the marketplace to have worth. What does it mean to create work that isn’t directed toward the cultural conversation of the moment—or even an audience, for that matter—but expects to be understood and appreciated in a more receptive time?

They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us by Hanif Abdurraqib

Hanif Abdurraqib’s essay collection They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us chronicles what it is to be Black in 21st-century America through multiple frames, primarily music. Nina Simone, My Chemical Romance, Whitney Houston, Prince, The Weeknd, and Chance the Rapper are central figures—as is the concert venue. In one wrenching moment, Abdurraqib recalls seeing Bruce Springsteen in New Jersey a day after visiting Michael Brown’s grave. The only other Black people at the concert are ushers and vendors, which leads Abdurraqib to insight: “[The River] is an album about coming to terms with the fact that you are going to eventually die, written by someone who seemed to have an understanding of the fact that he was going to live for a long time.” Abdurraqib wonders how it would be to live in a country where no one is killed, and all its citizens, regardless of race, were entitled to the “promise of living.”

The Time of Our Singing by Richard Powers

Richard Powers’s eighth novel dramatizes the story of a couple brought together in response to racism. David, a white German-Jewish physicist and Delia, a Black woman from Philadelphia, meet at Marian Anderson’s 1939 concert on the Lincoln Memorial steps after the DAR had stopped her from performing at Constitution Hall. In time, the couple’s two sons become classical musical prodigies, one a gifted singer, the other his piano accompanist, while their daughter distances herself from the family and joins the Black Panthers. A single question—“Where do we come from?”—yokes the book’s contrapuntal threads, time-traveling between past and future, as the family unravels. At one point, the pianist brother thinks, “Every sure thing was lost in the nightmare of growth.” And yet this book’s fascination with the possibility of self-invention exhilarates its symphonic form.

Why Karen Carpenter Matters by Karen Tongson

Karen Tongson queers her namesake in Why Karen Carpenter Matters, which is another way to say it’s a book of questions. Why does that singular voice, originally directed to conservative white listeners in the 1970s, have such meaning for brown, Black, and LGBTQ+ communities today? Why Karen Carpenter Matters not only considers The Carpenters’ history alongside Tongson’s migration from the Philippines to the sprawl of southern California. It shines a spotlight on the perfectionism that ultimately shaped Karen Carpenter’s sound and eventually brought her to harm. In this loving book, Karen’s significance to the writer is never easy, never without complexity: “Karen Carpenter is, at once, both my blessing and my burden.”

Wonderland by Stacey D’Erasmo

Anna Brundage, the 44-year old narrator of Stacey D’Erasmo’s Wonderland is an indie singer-songwriter who releases a comeback album after believing her performing days were behind her. This is a novel about reinvention, second chances, and how an artist navigates a niche position over the long run, especially when it comes to money, romance, rootlessness, and a life on the road. Moving between multiple points in time, Wonderland’s sentences about the power of music are electric: “The record sounded like a dress falling off a bare shoulder and a girl falling down a well.” And: “I was reaching for a train as it disappeared…Now I’m trying to go back to a place I’ve never been.”

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.